17 November 2022

Strategy

In the age of digital transformation, platform and ecosystem strategies are all the hype. The perceived success and winner-takes-all scenarios fuel their popularity today. From discussions and strategy workshops with business leaders I found that bringing some structure for a better thinking about this admittedly complex topic could prove helpful. In this article, I would like to create more clarity by giving an overview, provide concise definitions, sharing insights, and reflect on a few comprehensible examples.

Overview

It seems that everybody wants to be a platform or ecosystems business these days – or have at least a corresponding strategy in place. The motivation for it is clear: the world’s most valuable companies are all platforms3.

Therefore, you also want to be in the platform business. Or even create an ecosystem. How so? And what’s the difference?

As often with hyped terms and trends there is some confusion. However, you certainly don’t want just to follow or even invest in buzzwords.

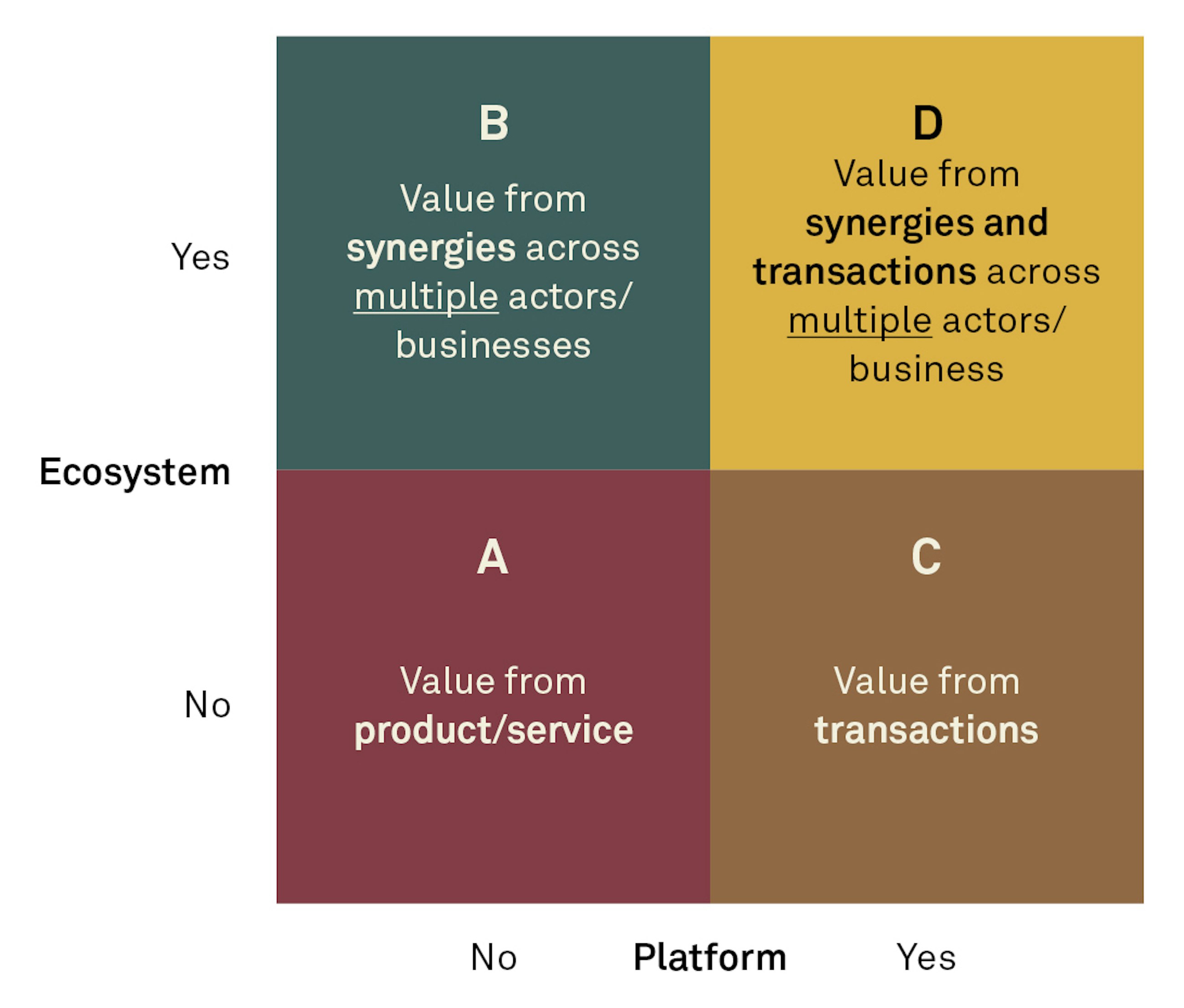

Simply put, a distinctive definition of “platforms” and “ecosystems” (adapted from reference 1) would be:

- A platform generates value by facilitating third parties’ transactions.

- An ecosystem is a linked group of actors/businesses providing complementarities for an overall value proposition .

In 'Don’t Confuse Platforms with Ecosystems'1,, Andrew Shipilov and Francesco Burelli provide us with an according 2x2 matrix of how platform and ecosystem intersect.

How does this inform strategy development? What does it mean for business models?

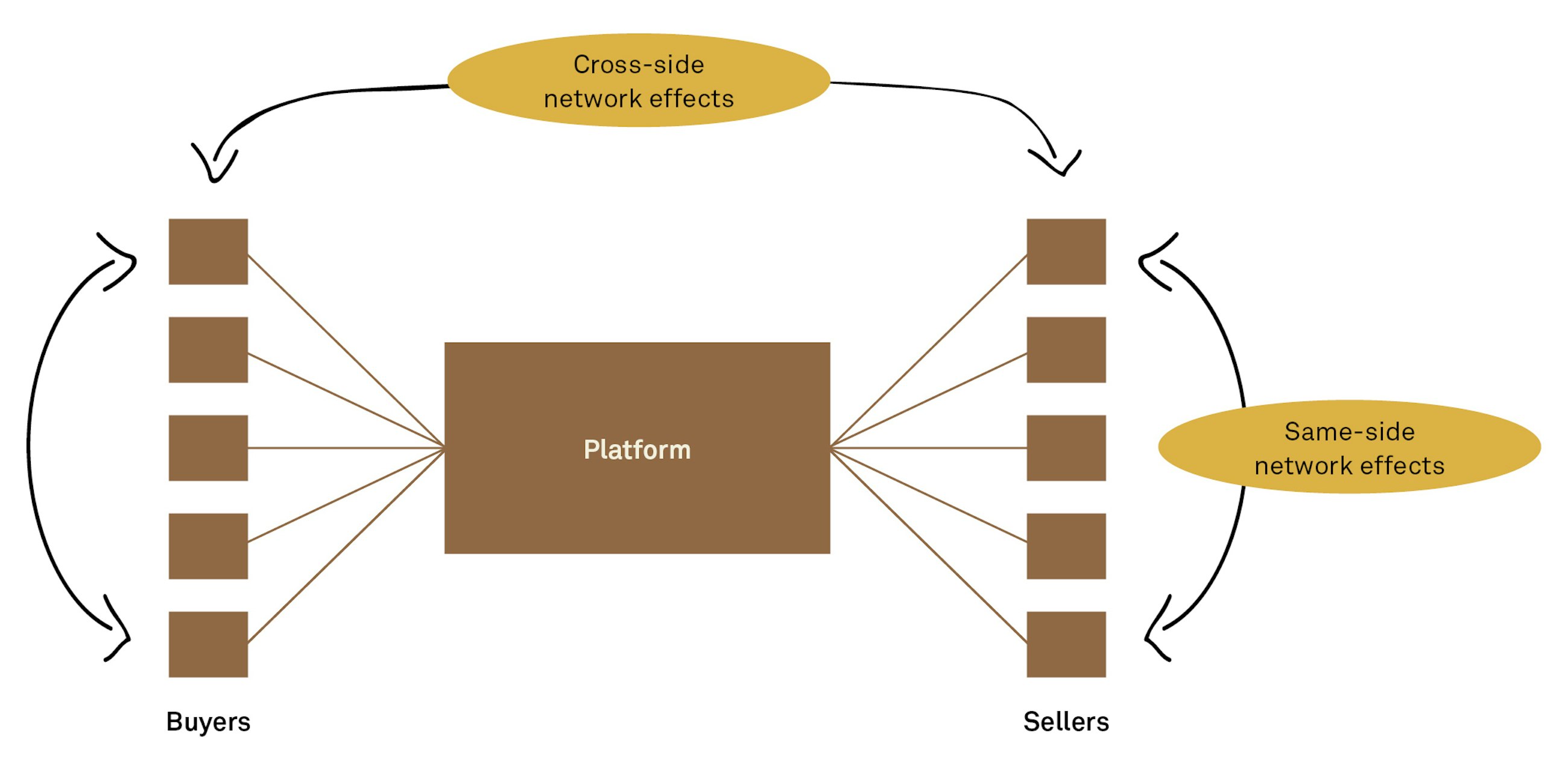

Let me bring an additional viewpoint: the concept of network effects.

- Same-side network effects (among buyers and among sellers)

- Cross-side network effects (across buyers and sellers).

The “same-side” network effects are interconnections between users. As an example, the more user-generated content available on Instagram the more attractive for potential other users it becomes to join. Another example would be user reviews on Amazon, where a lot of users means more and better information for buyers.

“Cross-side” effects are about scale. For example, the more sellers a platform features the more attractive the platform becomes for buyers. Think about the number of movies available on Netflix: the more supply, the more attractive for viewers. Conversely, the more viewers on the platform, the more interesting for studios it becomes to distribute movies on the platform.

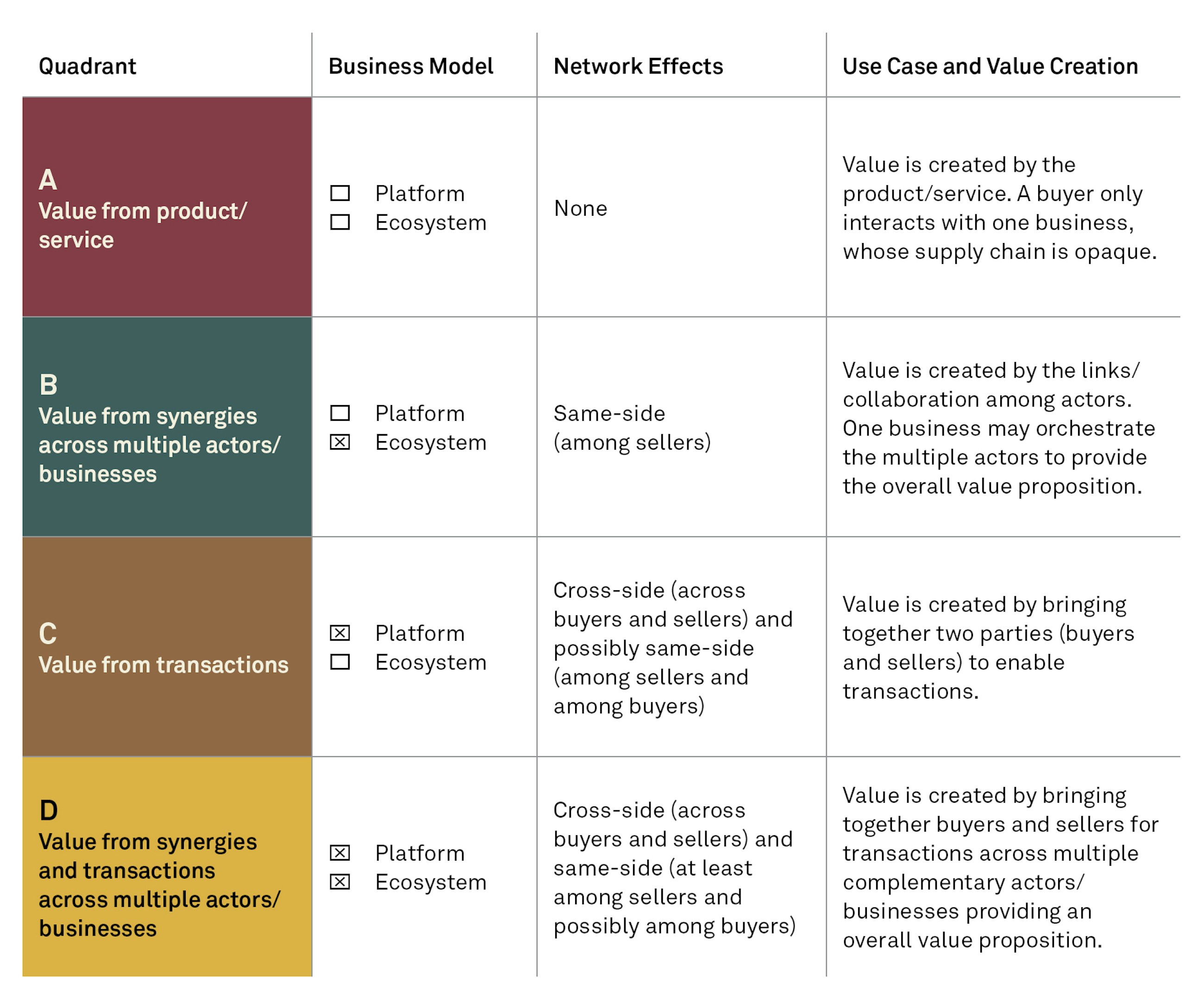

Let me summarize the viewpoints “Platforms & Ecosystems” and “Platform Network Effects” into one table for a better discussion:

Strategy and Approach

So, how to go about platform and ecosystem strategies? Should you build one or join one?

Entering the platform business?

As a strategist, you should ask yourself: will you enable third party transactions?

If yes, you are moving into the platform business. If not, don’t bother about platform strategies for your own business – but maybe think about joining a platform.

However, when you want to bring together two-sided markets, you need to provide value to transactions – you need to inject trust, make a fragmented market transparent, resolve inefficiencies in the market, bring a lot of users to the table, provide superior matchmaking, etc.

If you also provide the product/service for the buyers yourself you are not only starting to compete with the sellers on your platform, you may also move from quadrant (C) – platform – to quadrant (A) – product/service – over time, losing the platform appeal as you are not exclusively in the “value from transactions” business anymore. However, this is a strategic move that we can observe in the market again and again.

As a case in point, Amazon started out as a book seller. Only later it opened its website for third party booksellers – a concept they have extended into their online “Amazon Store” across all possible retail categories today. Therefore, Amazon moved the the other way: from quadrant (A) – product/ service – to quadrant (C) – platform. If you are a retailer thinking about opening a store-in-store on Amazon it helps to understand platform strategies and in particular Amazon’s actual strategy. At first sight, it may look tempting. Amazon provides you with reach and a lot of potential customers. However, Amazon may also become your direct competitor instead of just providing value to your transactions. Amazon collects data on your product and transactions and may be in an advantageous position to compete with you, cloning your value proposition and offering. If you take Amazon’s vision seriously (and you should), take a close look as it says “Our vision is to be earth’s most customercentric company”. So make no mistake: Amazon will always give preference to their end customers. You are not the primary customer of Amazon as a third party store. Maybe you are better off by joining another platform, one that is strategically better aligned with your own interests (like Shopify for example). Joining a platform is also a strategic decision (not only to become one) and for any business, it is good to understand the dynamics of platform strategies from all sides.

Of course, the strategic move in the other direction, from quadrant (C) – platform – to quadrant (A) – product/service, is also common.

When Uber begins to treat its drivers as employees instead of independent self-employed contractors, this is certainly not a deliberate move. However, we can witness the strategic implications by way of example. As soon as Uber’s drivers become its employees it basically starts providing the product/services by its own means (even if the cars may still be owned or leased by the drivers). In that, Uber becomes much more like a traditional taxi company – a single-sided business. And that is neither what Uber wants to be nor what their investors want Uber to be. Uber’s fight to keep its status as a platform that enables transactions between passengers and drivers is not only about their costs but inherently about its business model. And that is even more fundamental for Uber’s self-conception than just defending the benefit of being asset-light as a platform business. From Uber’s perspective, its approach to assert control over the way its drivers work (setting fares, terms & conditions, etc.) serves to create trust, efficiency, fairness, predictability, quality, and transparency – success factors for any valid platform. On the other hand, we can see that the increasing public resistance Uber is facing from workers and regulators reveals another problem: that of platform power and monopoly. In the case of Uber however, the hard logic of platforms may by itself render its strategy unsustainable as Uber is subsidizing both sides of the market (drivers and riders). As a consequence, Uber may in reality look more like a single-sided business. In that, Uber has less platform power as it may seem when investors discontinue subsidizing a money-losing business. After all, failure is more likely than winner-takes-all in platform strategies.

Entering the ecosystems business?

As a strategist, you should also ask yourself: will you provide (and orchestrate) complements from other actors for an overall value proposition?

If yes, you are moving into the ecosystems business. If not, you may well be part of an ecosystem (e.g. as an SAP implementation partner) or use aspects of ecosystem approaches (e.g. for growing faster internationally through partners). Therefore, you don’t necessarily need to be the owner of the entire ecosystem. However, if you want to be the creator of an ecosystem it will be a good exercise to first assess under what circumstances you yourself would join the ecosystem as a complementor in order to understand the multifaceted value you need to create and the associated success factors for shaping such a system.

Bringing together multiple actors to provide on an overall value proposition is a business orchestration challenge. Often, you need to provide a successful product (or platform!) first in order to pull off an ecosystem.

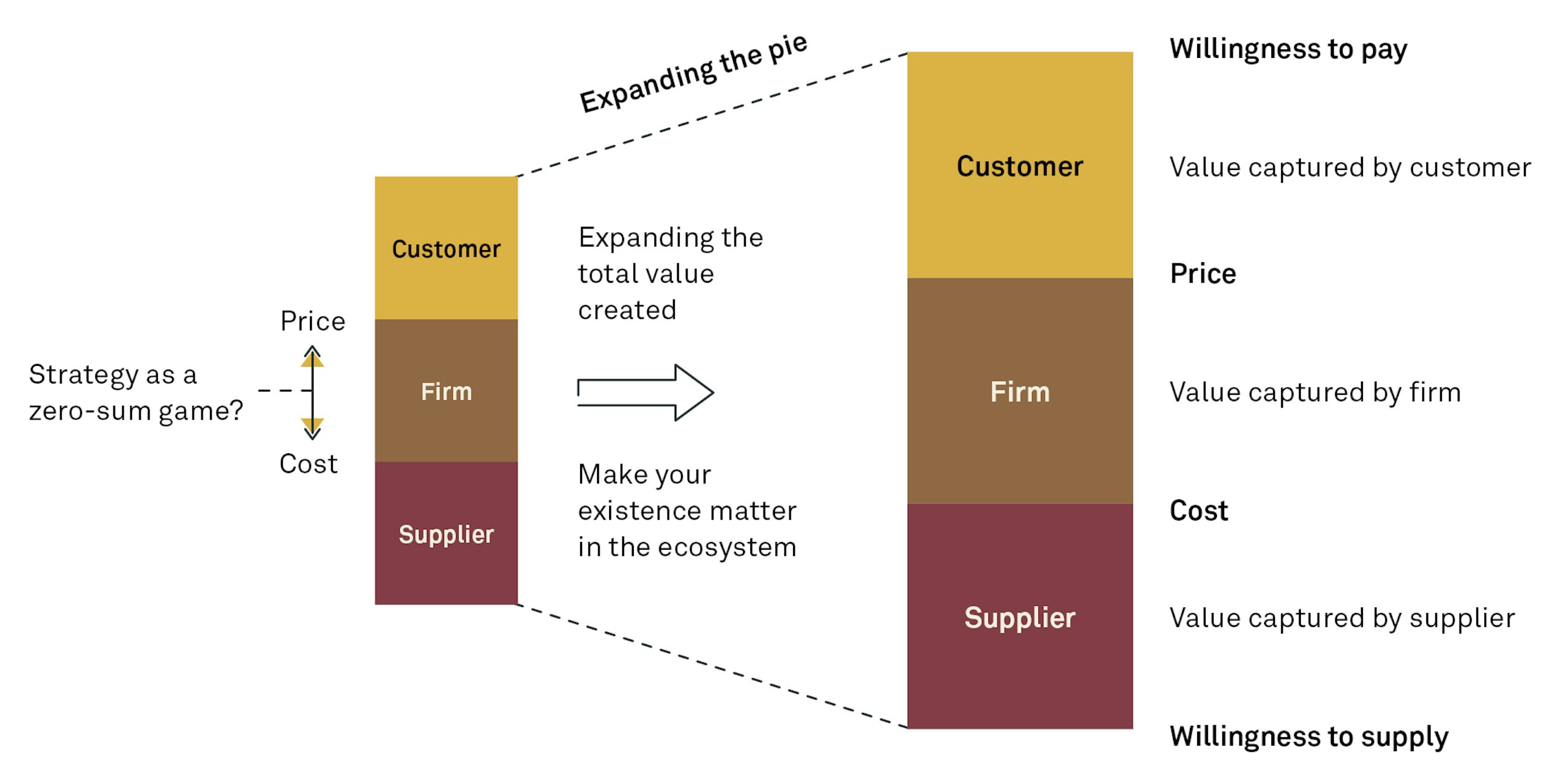

For ecosystem strategies, it is important to rethink the traditional strategy mindset, which sees strategy as a zero-sum game. It’s not only about how much value you capture between your suppliers and customers. It is about about how much value you create for everybody by expanding the pie. The strategic question you should have at the forefront is: How do you create a difference that matters in your industry and beyond?

Ecosystems are about expanding the pie. So how do you make the pie bigger for everyone?

The company that created the greatest value in history as the catalyst of a whole ecosystems is probably Microsoft. Over the course of two decades, Microsoft was able to weave a fabric of technology partners (e.g microprocessor companies like Intel, AMD, etc.), PC manufacturers (Dell, Lenovo, etc.), software vendors (B2C and B2B – from computer games to financial accounting) and software developers. Despite its sometimes aggressive business practices (e.g. web browser war with Netscape) and the well-known antitrust issues along the way, the Microsoft universe was by any comparison a remarkably open business system that benefited a staggering amount of participants.

The value and success of ecosystems comes not from a better product (see Apple in the 1990s) but from the better ecosystem – in Microsoft’s case it has been the network effects from the number of applications, licenses, and partners.

Combining platforms and ecosystems

Ecosystems are inherently difficult to build from the ground up. So where do you start?

First of all, it is important to realize that you don’t necessarily need to be the ultimate orchestrator of the ecosystem to profit – you can be a partner, technology or platform provider, a complementor, or reseller (see also reference 2).

If you strive to be the orchestrator of an overall value proposition, you probably need to build a successful platform business first.

Then, build an ecosystem around your platform as extension to grow the pie. This is most likely the most promising approach to combine platforms and ecosystems.

Certainly, platform and ecosystem strategies remain one of the most advanced domains of strategy.

References

1 Don’t Confuse Platforms with Ecosystems, Andrew Shipilov and Francesco Burelli, December 2020.

2 The Five Essential Roles of Corporate Ecosystems, Andrew Shipilov and Francesco Burelli, February 2021.

3 The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power, Michael A. Cusumano, Annabelle Gawer and David B. Yoffie, May 2019.

4 The Strategist: Be the Leader Your Business Needs, Cynthia Montgomery, May 2012.