14 November 2019

Make it simple or forget it. If we want to create value through our change projects, we must make it simple for the people involved to act in the desired way. There is no point in designing projects and making sure to complete deliverables if we forget that people are the strongest common denominator in virtually every change process. Within our project, things can be a little demanding, and that is okay. But as soon as we start involving colleagues, customers or citizens, it must be simple – because no change means no benefits realisation.

As professionals, we tend to use the same old tools we have been using for years and are skilled at using – and if your favourite tool is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Sometimes we realise too late that this is not the case. If we are comfortable using the well-known hammer, it is difficult to spot the benefits of using a screwdriver.

In almost all organisations, we struggle with wringing the benefits out of change projects. But if you stop for a minute and look around, you will see that there are many different views on how to make change happen and realise the benefits from change projects. It is still important to maintain the traditional focus on the production of IT systems, processes or products, but it is not the main priority. Even though our deliverables may be a little behind schedule, we will still get the IT system, the process or the product done, but ticking off all the deliverables on our list does not equal benefits realisation.

If you want to succeed in creating value from your change projects, there are three key areas to address:

- Design and manage your projects so that they maximise benefits realisation.

- Follow up on benefits realisation.

- Create the change necessary to realise the benefits on the first try.

The benefits realisation method is designed to focus on the first two areas.

Benefits realisation requires you to focus on the people who need to change their behaviour

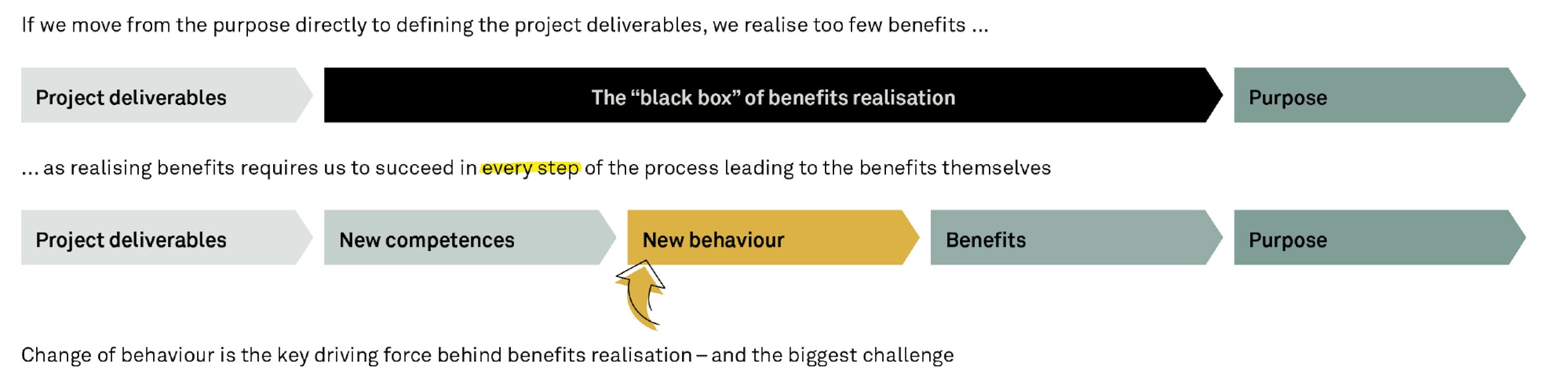

Traditionally, we tend to concentrate on “the ends” of the benefits realisation process, i.e. the purpose of the project and the production of the deliverables. This often leaves a “black box” in the middle of the process untouched (see figure 1). We define a list of deliverables based on the project purpose, and then we make sure to produce the deliverables and hope for the best. Sometimes – but far from every time – the results turn out well. However, according to Gallup, this approach means that we only realise the benefits from the business case in one of three projects.

In order to realise the full benefits potential from our projects, we need to focus on the entire benefits realisation process. Figure 1 shows the benefits realisation process and lays out the cause-and-effect relationship we need to establish in order to reach the desired benefits in our project. We start with the purpose and make our way from right to left in the figure below, unfolding the project so as to designing the project that realises the desired benefits.

Because the benefits realisation process is based on a cause-and-effect relationship, it requires us not only to succeed with project deliverables but also to build the necessary competences and create a change in behaviour if we are to realise the full benefits potential. It is more or less irrelevant whether we have delivered our IT system, product or process at the agreed time, within the agreed budget and in the agreed quality, unless we have succeeded in forming the new behaviour among our colleagues that is necessary for us to realise the benefits.

For years, most organisations have followed a structured approach designed to make them good at producing project deliverables and training staff to acquire the necessary competences. The same cannot be said about changing behaviour. The “change part” is seldom tackled in a structured and efficient way, and therefore we often fail to create the behavioural change we need. An approach to change that actually works becomes key to benefits realisation in most organisations. Without change there can be no benefits realisation.

Behavioural design puts people first in the change

So far, we have focused on identifying and targeting the benefits of the project, but we have not looked at behavioural change in detail. We have simply visualised that changing behaviour is an important aspect and have yet to consider how to accomplish it. This is where behavioural design comes into play.

Behavioural design has arisen from centuries of studies on how people make decisions. These studies have provided a new understanding of the fact that in most cases, people’s decisions are not especially rational; rather, they are made based on bias and heuristics or on account of the habits we have developed. This new understanding initially made behavioural design popular in the context of e.g. pricing goods (there is a reason why there are only three different sizes of drinks available in cinemas) and of “nudges”, one of the best-known examples being the fly in the urinal at Schiphol Airport. Fundamentally, behavioural design is a study of the human being in its context, and the method was well suited to explain why we act the way we do. However, behavioural design version 2.0 should also be applicable in major transformations, e.g. cultural changes, digital transformations, agile agendas and so on.

Three things are required for behavioural design to make a difference in a business- critical change:

- A strategic hook: You must make the purpose of the change clear in order to gain organisational support for the use of behavioural design.

- A project framework: It must be possible to link the behaviour you create directly to the value you wish to realise.

- You must adapt the scale of the method: You need more than a “surgical method” that solves only a single problem. You must be able to see the big picture at the same time as taking the surgical approach to each individual part of the behaviour you are looking to change.

Benefits realisation is a perfect match for behavioural design

In the context of benefits realisation, we need behavioural design to demonstrate precisely how we are to change our behaviour. When it comes to benefits realisation, there is a clearly defined space in the project for behavioural design (the change track) as the means to ensuring a successful change. In the context of behavioural design, benefits realisation provides the strategic hook and the project framework we need. Behavioural design must be able to function as an extension of the structures we work with in projects, and it must play a role in the design of measures for change. In this way, the results of behavioural design become the framework for how we approach, understand and tackle the problems and needs, ensuring that we put people first when defining the solutions.

The principles of beavioural design: Simplicity above all

- Reduce the effort required to do the right thing. In most cases, people understand the rationale behind an upcoming change, and in most cases, they are actually open to change their behaviour. The problem is that we tend to position the narrative about the necessary change too far away from a tangible, relatable example. At the same time, we forget that the common denominator in all changes is the individual, who will be required to act differently tomorrow. That is why behavioural design is so crucial to realising benefits. Using the method enables us to bring the vision down to earth and to have it appear “smaller” by focusing on the person rather than the solution.

- Build on what already exists. Nobody spends the whole day standing in the corner doing nothing. So, if we are aware of what it is that drives people’s current behaviour, we can use this as a lever to nudge them in the direction of the new behaviour without overloading them with too many surprising new initiatives.

- Get out there and give it a try! There is no way we are going to solve the problem from the meeting room. As soon as you can, get out of the room and take a good look at the people and elements that constitute the ultimate goal of the change. Be curious and challenge your own assumptions.

Behavioural design in practice

It is simple to integrate behavioural design in the practical work of changing behaviour. Instead of looking at a single problem, we now view the change as a series of small changes in behaviour. Behavioural design features a set of activities we can use to establish which behaviour we need to target to realise the benefits from the project and how best to do so:

- Insight study

- A thorough barrier analysis

- Use of insights and the barrier analysis to shape our initiatives

If we are to perform a series of surgical interventions, we have to gather the necessary insight into what is going on among the employees in the organisation where the change is to take place and what are currently the biggest barriers to converting our wishes for new behaviour into reality. In the process, we must generate the organisational commitment that a successful change requires. There must be a willingness to want to examine and challenge the preconceptions regarding what is necessary to make a change. We can only succeed in this if we step outside the project’s ivory tower and immerse ourselves in the everyday life of the organisation.

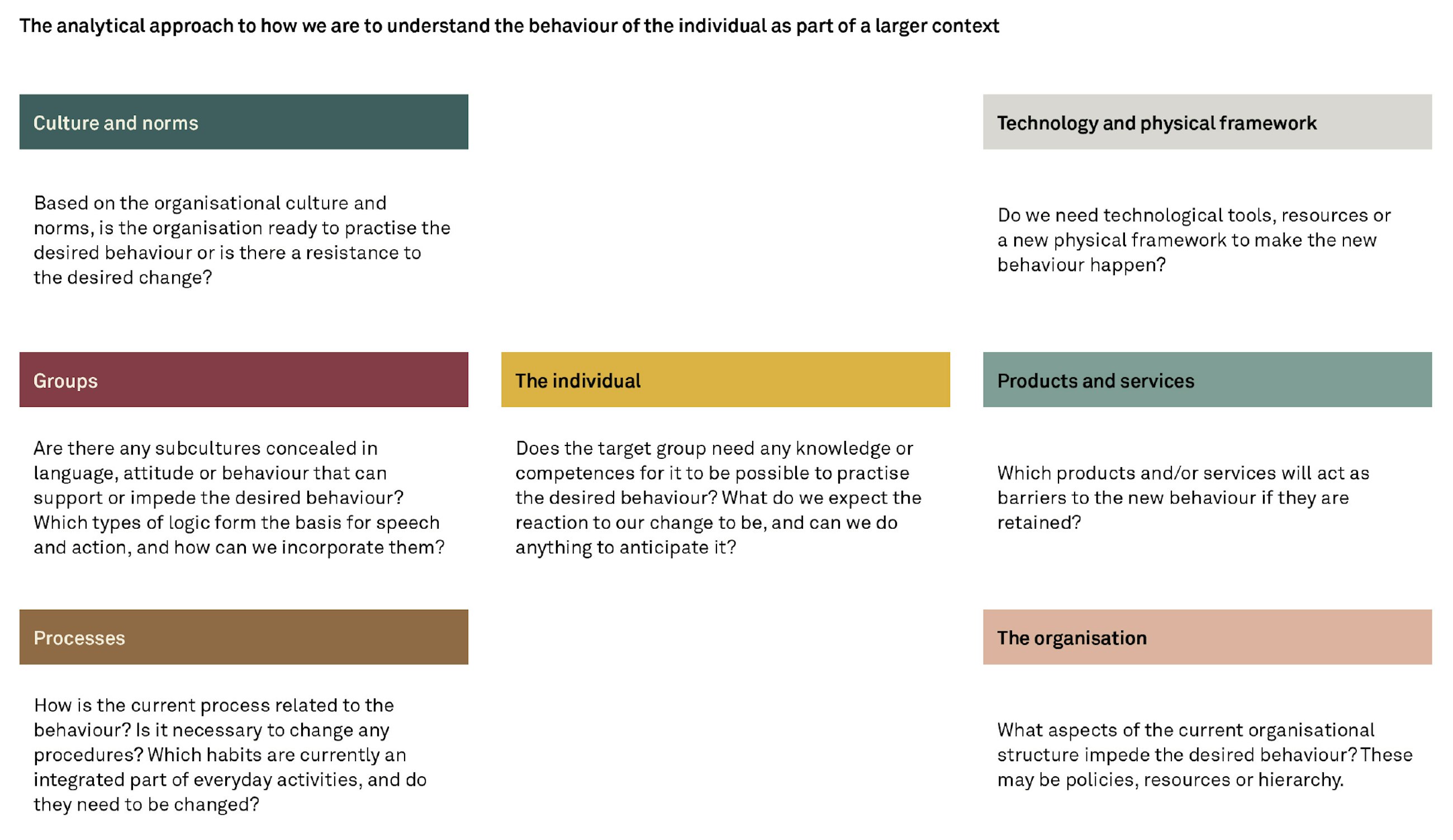

The barrier analysis is a way in which to divide the problem into more well-defined categories. Doing this also enables us to see the numerous facets a given solution can entail. The objective is not to find something in all categories but to find solutions in those places where they have the greatest effect. Another advantage of the barrier analysis is that it highlights potential “solution hooks” that we will almost certainly benefit from leveraging in our change initiative.

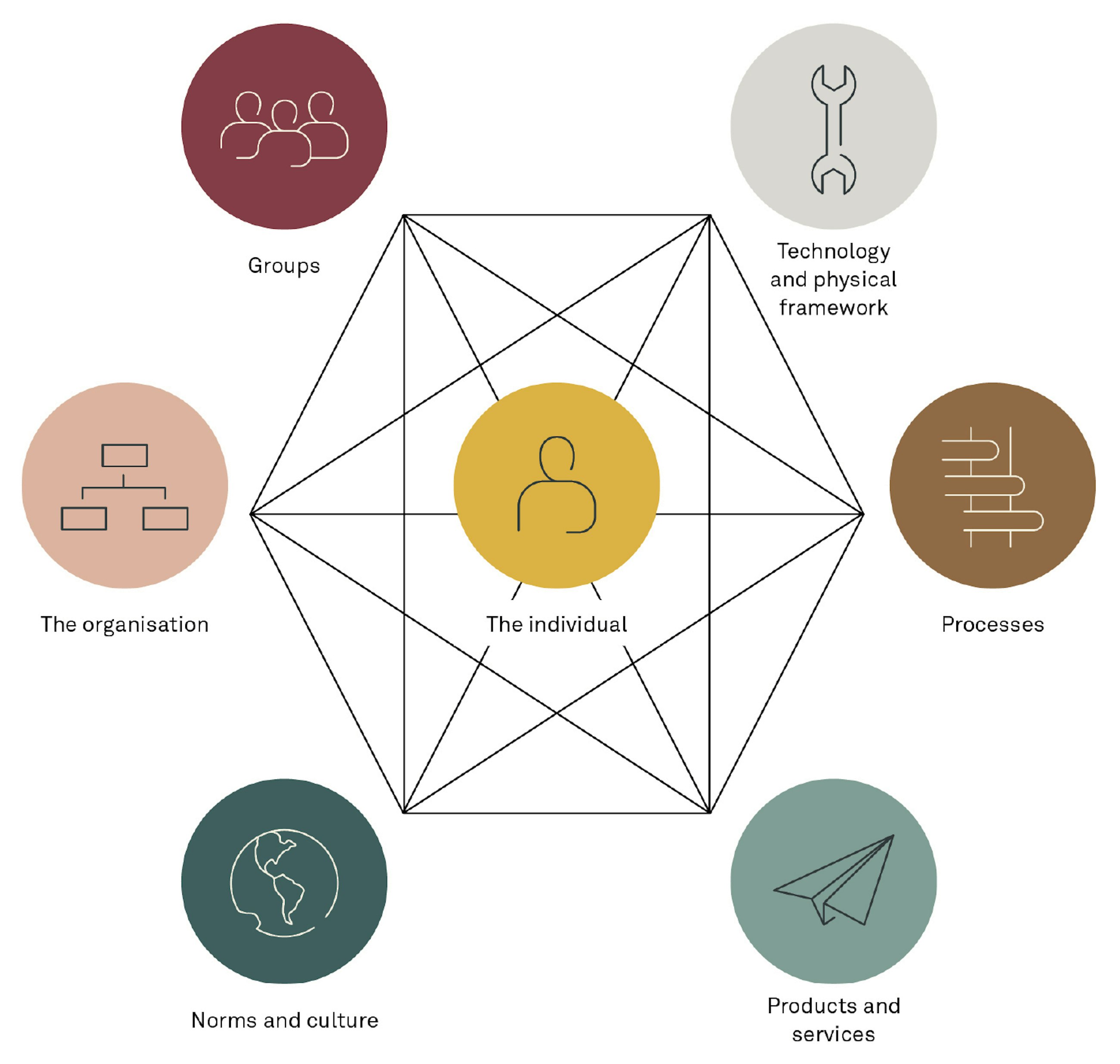

In order to understand the barriers for the individual, we will use Maurer’s levels of resistance1, which allow us to anticipate the resistance we are likely to encounter and what we need to do to help the individual pass smoothly through the change. The remaining barriers can be divided into organisational and technical barriers (see figure 3). What is it in the context of the individual that powers the current behaviour, why is it attractive, and how does what is happening here and now serve as either a barrier to or a lever for reaching our desired goal?

The most important aspect of the barrier analysis is for us to separate elements of the context from one another. Here, we apply a “mixed methods” approach, where both qualitative and quantitative methods are to help unveil a depth in each element. Lack of commitment can, on the one hand, be due to the existence of a subculture (language, logics and local truths) that impedes measures initiated by the headquarters, but it may also be due to established processes locking current behaviour firmly in place. The way in which we deal with the two barriers will differ greatly, and in this way, we can enrich the solution space much more accurately as a result of the barrier analysis.

Wrap-up

In this article, we have attempted to put forward a new way of approaching change by combining benefits realisation and behavioural design. Where benefits realisation leans towards a commercial context and establishes the argument for change, behavioural design can help ensure that such a change actually takes place with greater ease and precision than before. Behavioural design combined with benefits realisation results in a value-creating method framework.

Notes

1 Maurer has defined four levels of resistance: “I like it”, ”I don’t get it”, “I don’t like it” (emotional reaction) and “I don’t like you” (reaction based on lack of trust).

Sources

Rytter, R., Lind, J. og Svejvig, P. (2015). Gevinstrealisering [Benefits realisation]. Akademisk Forlag, København.

Maurer, R. (2010). Beyond the Wall of Resistance: Why 70% of All Changes Still Fail – And What You Can Do About It. Bard Press, Austin, Texas.

Clear, J. (2018). Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones. Penguin Random House, New York.

Heath, D., Heath, C. (2010). Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard. Broadway Books, New York.

Koester, T. (2007). Terminology Work in Maritime Human Factors. Situations and Socio-Technical Systems. Copenhagen: Frydenlund Publishers.

On average, projects go over budget by 27 percent of their intended cost. (Harvard Business Review)

On average, one in six projects saw a budget overrun of 200 percent. (Harvard Business Review)

55 percent of project managers cited budget overrun as a reason for project failure. (IT-Cortex)

31 percent of project managers cite meeting their budget as a criterion for project success. (IT-Cortex)

IT failure rates are estimated to be between 5 and 15 percent, accounting for a loss of $50–$150 billion per year in the United States alone. (Harvard Business Review)

Projects with budgets over $1 million have a 50 percent higher failure rate than projects with budgets under $350,000. (Gartner)

Organisations with 80 percent or more of projects being completed on time and on budget waste significantly less money due to poor project performance. (PMI, 2017)

Project management initiatives save companies 28 times more money since their output is more reliable (PMI, 2017).