Article

How to make better decisions in supply chain planning – and where AI can support

Published

21 January 2026

Today, most supply chain executives recognise AI’s potential to transform their supply chains – from design and operations to planning. Yet, while AI models have demonstrated clear improvements in demand forecasting accuracy, their impact in other core planning areas such as inventory, supply network, production, and sales and operations planning remains limited. This raises an important question: why has AI succeeded in some areas but not others?

This article seeks to answer that question by focusing on two key points:

- Understanding the decision chain to identify where AI use cases can have real impact

- Exploring how limiting AI to the ISO definition often means improving decision inputs rather than the decisions themselves

Even if you do not work directly in supply chain planning, these insights offer a fresh perspective on how AI can help you make better decisions.

The AI use case race

The race to develop AI use cases has been underway for some time, and if your project’s business case includes the two famous letters – AI – you are more likely to secure funding than if it did not. This is true both internally within companies and if you are a software vendor or advisor competing for attention. It is also why this article includes the word ‘AI’ in the title.

This phenomenon has both advantages and drawbacks. On the positive side, it has accelerated the number of implementations and frontier projects, bringing AI-driven solutions into business contexts and delivering benefits to some companies. On the downside, this rush has sometimes blurred the lines around what AI actually entails, causing confusion rather than clarity.

According to the ISO Standards, AI is “a branch of computer science that creates systems and software capable of performing tasks once thought to be uniquely human. It enables machines to learn from experience, adapt to new information, and use data, algorithms, and computational power to interpret complex situations and make decisions with minimal human input.” 1 This definition encompasses a broad range of technologies – from classical AI methods to modern machine learning.

In supply chain planning, where thousands of decisions are made daily across complex global networks, machines have long used data, algorithms, and computational power to interpret situations and make decisions with minimal human intervention. What is relatively new, and central to the ISO definition, is the ability of these systems to learn from experience and adapt to new information – and this is where machine learning, a sub-branch of AI, comes in, explaining why the terms AI and machine learning are often used interchangeably.

The key question for supply chain planning is not simply whether AI is being used, but how it can most effectively support better decision making.

Where AI adds value: From prediction to decision support

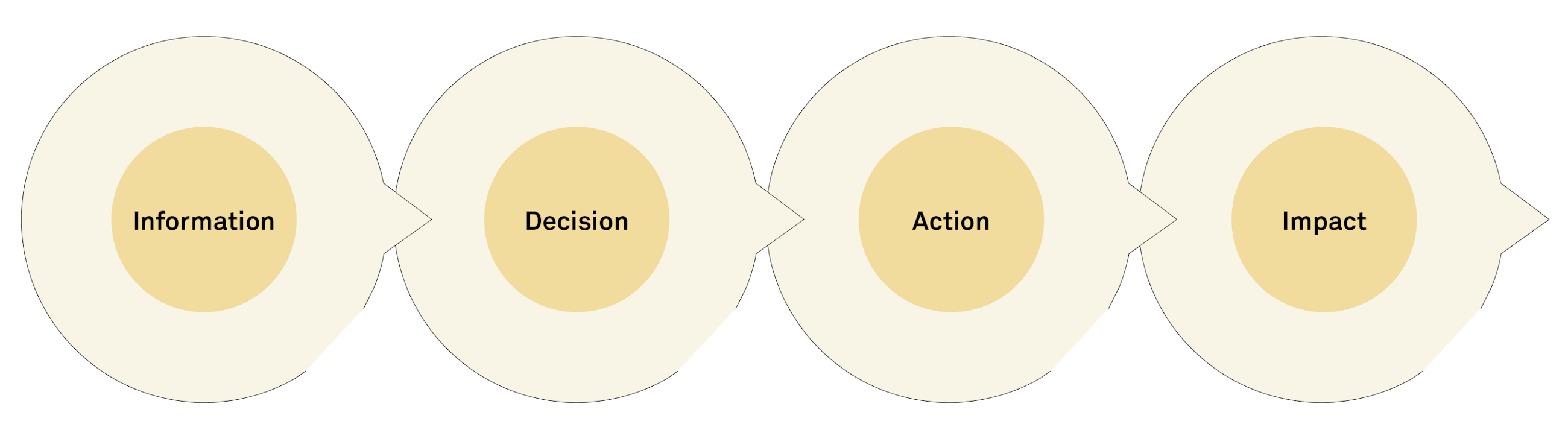

In the quest for AI cases in supply chain planning, it is important to understand the basic mechanism of decision making.

In the world of supply chain planning, an example could be:

(Information) Inventory below reorder point → (Decision) Decide to purchase product → (Action) Create purchase order → (Impact) Impact on cost and net working capital

As with all decisions, in a supply chain planning context it is important to define:

What is the information or trigger point for making the decision?

- How do you evaluate if the decision was good or bad?

- Which guardrails or policies guide the decisions – what do you want to achieve, and what should it be based on?

This means that the information provided to make a decision is the outcome of a previous decision, leading to a cause-and-effect chain.

In the example above, the first decision would be what the reorder point should be.

(Information) Updated sales and lead times → (Decision) Calculate reorder point → (Action) Update reorder point →(Impact) Increase or reduction in net working capital.

All supply chain professionals know these examples by heart and are aware that methods vary in sophistication and that flows can be automated, even without AI agents. Nevertheless, understanding the basic dynamics of decision making is important, since supply chain planning involves thousands of daily decisions, most of them automated and based on models of varying sophistication.

Signals vs. decisions

One of the most prominent AI use cases in supply chain planning – demand forecasting –primarily provides information that feeds into subsequent decisions. While choosing to rely on an AI-generated forecast is itself a decision, the forecast alone does not trigger replenishment, production, or purchase orders.

This does not mean that AI-generated forecasts fail to add value; on the contrary, they can significantly improve the quality of information available. However, it is the subsequent policies and decision logic that translate forecasts into actions and ultimately create business impact.

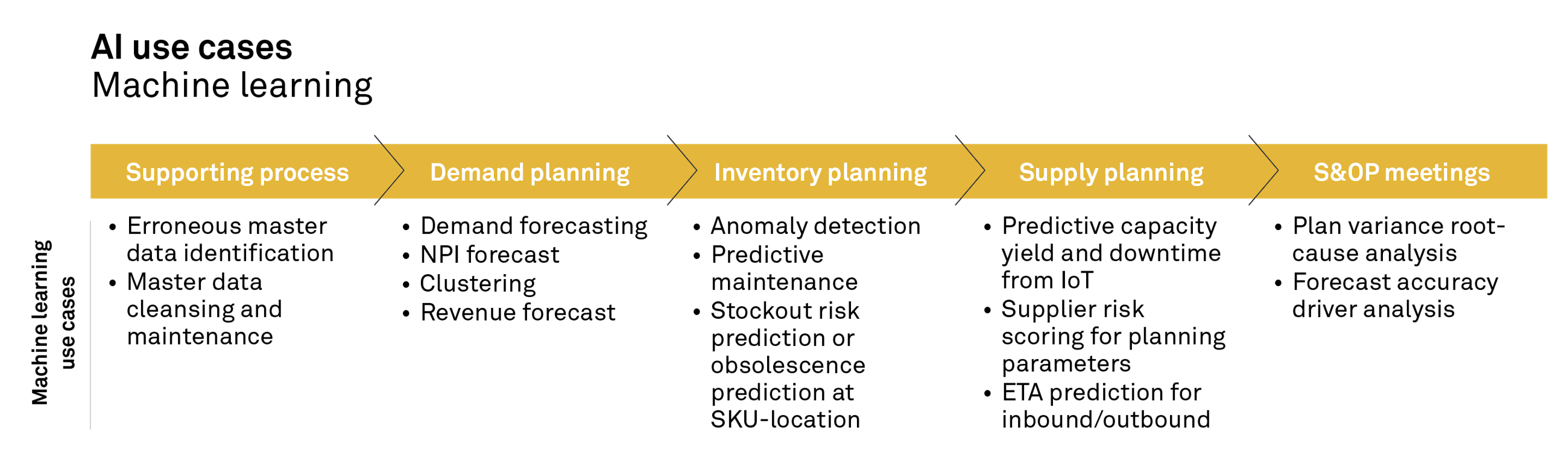

Examples of AI use cases in supply chain planning using machine learning

If we follow the ISO definition of AI, then “learning from experience and adapting to new information” implies that the use case must be based on a training set – in other words, on supervised machine learning models. Supervised machine learning models are well suited to pattern recognition and prediction and can adapt as new information becomes available.

However, they are not designed to define new decision policies – such as how much to purchase, where to produce, or when to ship. By nature, supervised machine learning models operate with a single objective regardless of the underlying business policy: to minimise error based on a training and validation set.

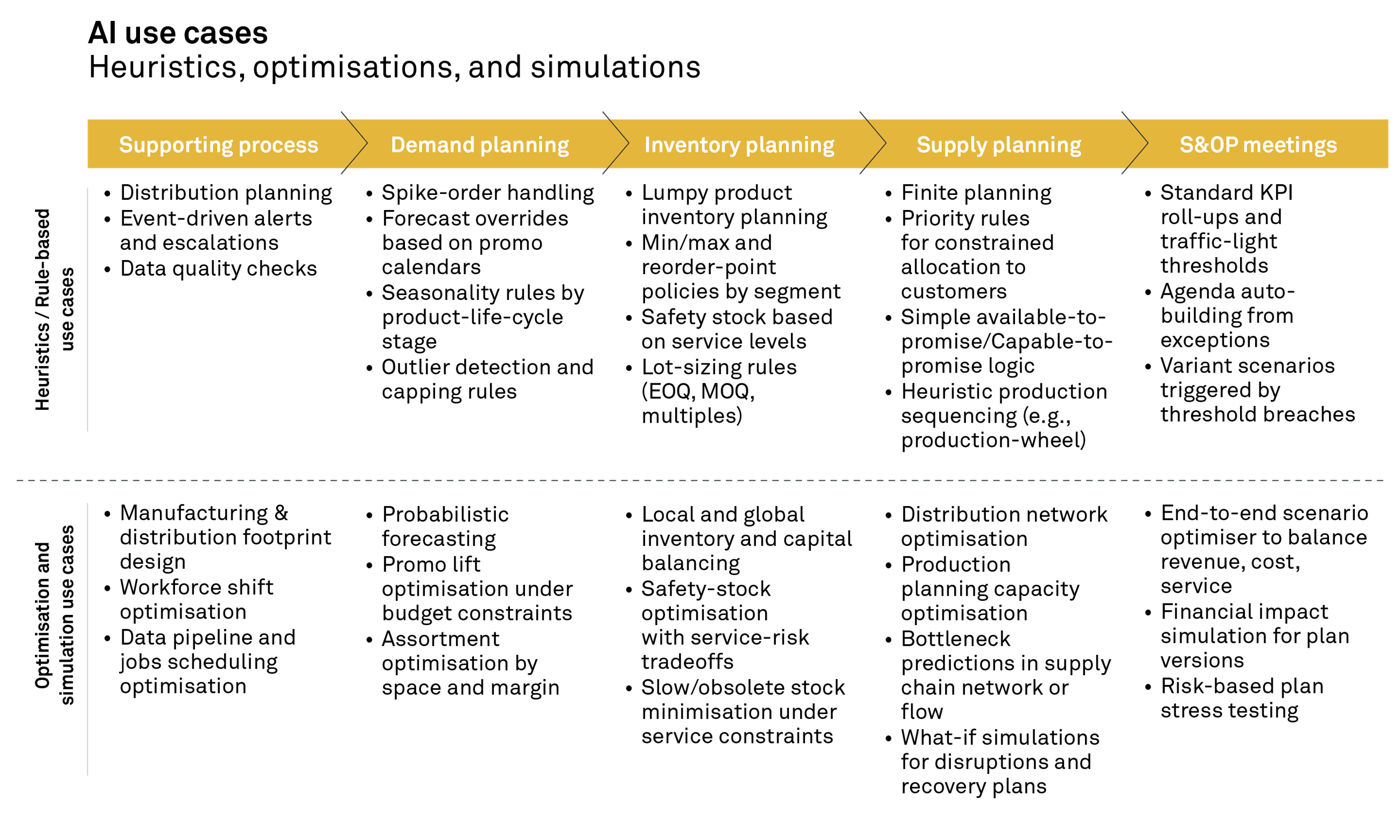

When deciding how much to purchase, where to produce, or when to ship, there are two common approaches to making the decision:

- Rule-based decisions (also known as heuristics)

- Deterministic optimisation

Both approaches rely on information, allow a decision policy to be defined, and lead to actions that create impact. However, they do not learn from experience or adapt their underlying logic over time. Of course, if the input information changes, the resulting decision – and therefore the action and impact – will also change. The decision rules themselves, however, remain unchanged.

Both approaches can still surpass human capabilities in terms of speed, complexity, and scale, and can make decisions with minimal human intervention. In that sense, the intelligence is not human, but artificial. That said, with heuristic approaches and optimisation, human creativity and judgement play a direct role in shaping the decision logic: you can define the policies you want to model and thereby guide the behaviour of the system.

Examples of AI use cases in supply chain planning using heuristics, optimisation models, or simulations

In a similar way to how a data scientist adjusts machine learning models by engineering features, training models, and tuning parameters, a modeller can define rules or design objective functions and constraints. The key difference is that machine learning models require a training dataset to learn decision rules, whereas rule-based decisions and deterministic optimisation can be modelled directly from policy and applied to new situations without being trained on historical data.

What was considered futuristic about machine learning in the 2010s – namely, its ability to derive rules directly from data – is both a blessing and a curse, as it also defines the limits of where machine learning can be applied.

If we take the ISO definition of AI and remove the element of “learning from experience and adapting to new information” – which, to us, corresponds to machine learning – what remains can still be considered artificial intelligence. This remainder overlaps to a large extent with classical operations research, which has delivered value-adding models to supply chain planning for decades.

This also widens the scope for AI business cases, as machine learning models can be used to generate information, while rule-based or optimisation methods can be used for decisions. This is also why there are relatively few machine learning use cases within supply planning, whereas many can be found within demand planning.

Furthermore, with increasing computational power at lower cost – and with quantum computing on the horizon – it is now becoming realistic to compute use cases that were previously unsuitable for the decision lead times required in supply chain planning.

Apply reinforcement learning to targeted planning decisions

A curious and critical reader may challenge the flow above and argue that decisions could be improved by AI if their outcomes are continuously evaluated and used to update policies, thresholds, and models. This leads us into the field of sequential decision making, where a series of decisions is made over time, with each choice affecting future options and outcomes.

According to Warren B. Powell, Professor Emeritus at Princeton University and author of numerous books on operations research, this represents the highest level of AI achieved so far. However, it currently works only for well-structured problems where it is possible to encode all the underlying physics of the problem into a computer.2

This is also where the AI approach of reinforcement learning comes into play, and where there is significant potential for new AI use cases. Reinforcement learning is well suited to problems with very large or effectively infinite solution spaces, where a trial-and-error approach can be applied. It is particularly useful in situations that require many sequential decisions, where the outcome of each decision can be evaluated and the model can adapt over time. However, it still requires an overarching policy and a clearly defined evaluation metric to be specified.

This is an area where AI readiness currently exceeds organisational and human readiness, and where successful application requires a clearly limited scope within supply chain planning. If applied across the entire planning process, there is a risk of repeating challenges seen with best-fit forecasting approaches in the 2000s, where each planning cycle produced different results – not because assumptions had changed, but because a different model performed marginally better.

In a large-scale supply chain, with thousands of decisions made every day, this can quickly lead to inconsistency and loss of trust. Applied to a well-defined part of the process, however, the potential benefits can be significant. Ultimately, it comes down to the capability and creativity of the designer: can the relevant physical constraints and intended objectives be captured in the model, and will it deliver additional value?

Shifting focus: From models to outcomes

You may have come across the term decision-centric AI, which is increasingly used by software vendors in supply chain planning. If decision-centric AI means that the focus has shifted from building models to improving the quality of actions and outcomes, then it is a welcome development and a sign that we are moving beyond the hype, with companies rightly expecting tangible value from AI implementations.

However, decision-centric AI should be understood less as a specific technology and more as a design philosophy. It combines reinforcement learning with optimisation, causal inference to uncover cause-and-effect relationships, and human-in-the-loop governance. Seen this way, it provides a set of design criteria for implementing automated, self-learning workflows that integrate multiple AI tools to support better decisions.

There is little doubt that decision-centric AI combined with sequential decision making will play an important role in the future. However, it requires a fundamental shift in mindset, governance, and capabilities – areas where many companies still struggle, as seen in current attempts to implement so-called end-to-end solutions. A necessary first step is to align on which decisions are made within supply chain planning, how those decisions are evaluated, and what information is required to support them.

Better data, better decisions

Finally, in the search for AI use cases in supply chain planning, we arrive at generative AI and virtual agents. While generative AI can be useful as an enabler for enriching and improving information ahead of a decision, it is unlikely to fundamentally change how supply chains operate or how decisions are made within supply chain planning.

Examples of AI use cases in supply chain planning using reinforcement learning and generative AI

More broadly, the value of generative AI – and to some extent virtual agents – lies primarily in labour-intensive processes. Supply chain planning, however, has for decades focused on automating planning and decision processes. While there is still room for further automation, it is more likely to be driven by machine learning models, rule-based approaches, or optimisation techniques, rather than by generative AI or virtual agents.

Decisions first, technology second

When exploring AI use cases in supply chain planning, it is helpful to start with the decisions themselves. Every decision can be improved either by enriching the inputs (information) that inform it, or by refining the policy used to translate that information into action. Viewed this way, potential use cases are naturally linked to a clear business or impact case, as they connect directly to which actions change and which outcomes are affected.

Ultimately, funding decisions should not be driven by whether a solution fits a particular definition of AI, but by whether it improves decision quality or efficiency in a way that triggers meaningful action and delivers impact. For this reason, it may be beneficial to shift the focus from merely searching for ‘AI use cases’ in supply chain planning to actually improving decision-making in supply chain planning. When that shift is made, AI – in one form or another – will often emerge as a valuable part of the solution.

Sources

International Organization for Standardization (ISO). https://www.iso.org/artificial-intelligence/what-is-ai

Powell, W. The 7 Levels of AI. CASTLE, Princeton University. The 7 levels of AI – CASTLE

Any questions?

Related0 4

Case

Read more

From regulatory noise to actionable change

How AI triage and RAG accelerate regulatory intake with explainable and auditable outputs.Article

Read more

CFO Advisory #1: Unlock AI value in finance

Learn quickly, experiment often, and adapt faster than the competition.Case

Read more