Three levers for the corporate learning gardener

12 March 2020

Learning is needed more than ever

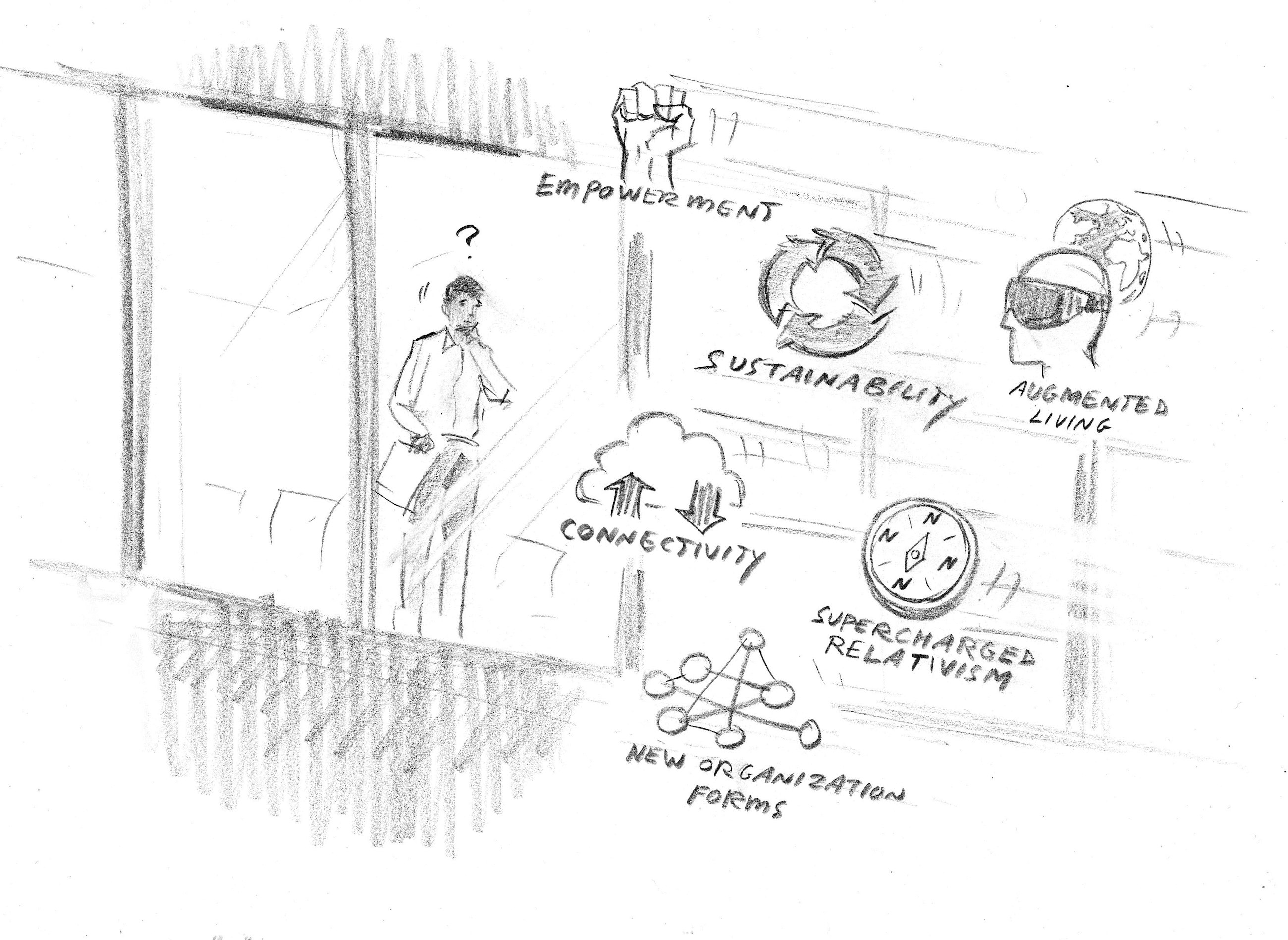

The world is changing. Global trends such as connectivity, new organisational forms, empowered humans, supercharged relativism, augmented living and a pervasive focus on sustainability are evolving at a higher pace than ever. Customers have access to knowledge at any time, and robots are replacing roles, jobs and functions1. These trends are resulting in a leap in the change of demands in competence for everyone in the corporate workforce. Learning is needed more than ever.

Responding to this change is imperative to organisational survival. However, the world outside is currently changing faster than competences inside are developing.

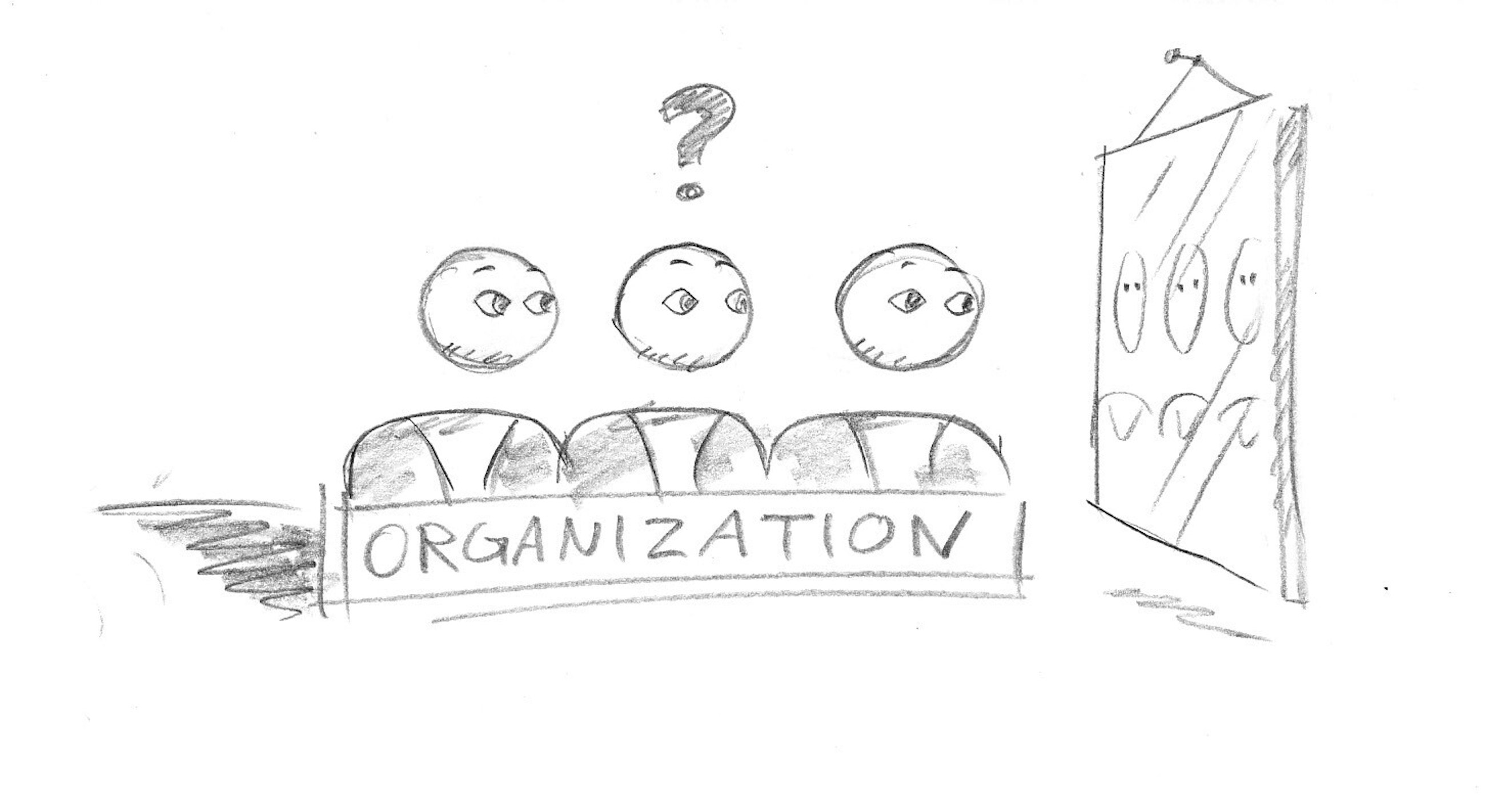

The transformations that take place in the world challenge the traditional corporate learning model. At Implement, we see that traditional and once successful models for corporate learning and development can no longer meet the needs for the changing demands in workforce competence.

In this article, we argue that this challenge calls for a transformation and a shift in mindset in how we understand and approach learning in organisations.

The transformation needed is anchored in our models of competence development. Our corporate learning models suffer from a legacy of “old-style” training, e-learning and corporate academies and are in many cases stuck in an old paradigm that limits the speed of and options for organisational adaption. Hence, we need to embrace a new paradigm for corporate learning.

Traditional learning models will no longer suffice

In a world where success is determined by the ability to cope with moving targets, unclear role expectations and competence needs, concrete learning goals and a fixed role-based curriculum will no longer do the trick. The traditional models of upskilling are hierarchical in their structure where a few experts determine the areas for growth and teaching the masses. This model is not scalable in the pace that the changing world is dictating. Hence, it will no longer suffice.

The need for reshaping the corporate learning model is reflected in these findings from a recent Harvard Business Review article2:

- 75% of managers from 50 organisations were dissatisfied with their company’s learning and development function.

- 70% of employees report that they don’t have mastery of the skills needed to do their jobs.

- Only 12% of employees apply new skills learnt in learning and development programmes to their jobs.

- Only 25% believe that training measurably improved performance.

A shift from learning content to a learning culture

Instead, we must shift our attention to continuous, network-based learning models that are flexible. In these models, everyone is a learner, and everyone is an educator. In such an organisation, everyone contributes his or her knowledge and experience to the broader knowledge base and, in so doing, helps form the organisation and the potential directions it can take. Such an organisation requires a culture of empowerment and openness to learning that, in turn, leads to flexibility and adaptive growth.

In organisational theory, this is known as “the learning organisation”. Such organisations are characterised less by learning content and more by a learning culture. Such organisations are places “where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole (reality) together” (Peter Senge, 1992). The concept of the learning organisation is not new at all, but this does not make the concept, or a reminder of it, less relevant today.

All in all, the concept of a learning organisation inspires a shift away from learning models centred on training towards models that are focused on creating the right everyday conditions of learning through a learning environment and culture.

But how do we broaden our scope of learning, and how do we facilitate better learning environments?

In this article, we propose a situational and holistic approach to corporate learning, focusing more on the right everyday conditions for learning (culture) than on formal training (content). This with the ambition of fostering more adaptable organisations that are fit for humans and fit for the future.

Learning happens all the time – more or less

To foster a situational and holistic learning culture, we need to start being more crisp on what learning actually is.

When we act, we learn. And when we have learnt, we act in new ways. Learning can be described as the process of acquiring new or modifying existing knowledge, behaviours, skills, values or preferences and, most importantly, being able to apply this into new contexts. Learning, then, has both a knowledge and an action component.

In this characterisation of learning, experience is key in creating, reproducing or modifying existing knowledge and behaviours.

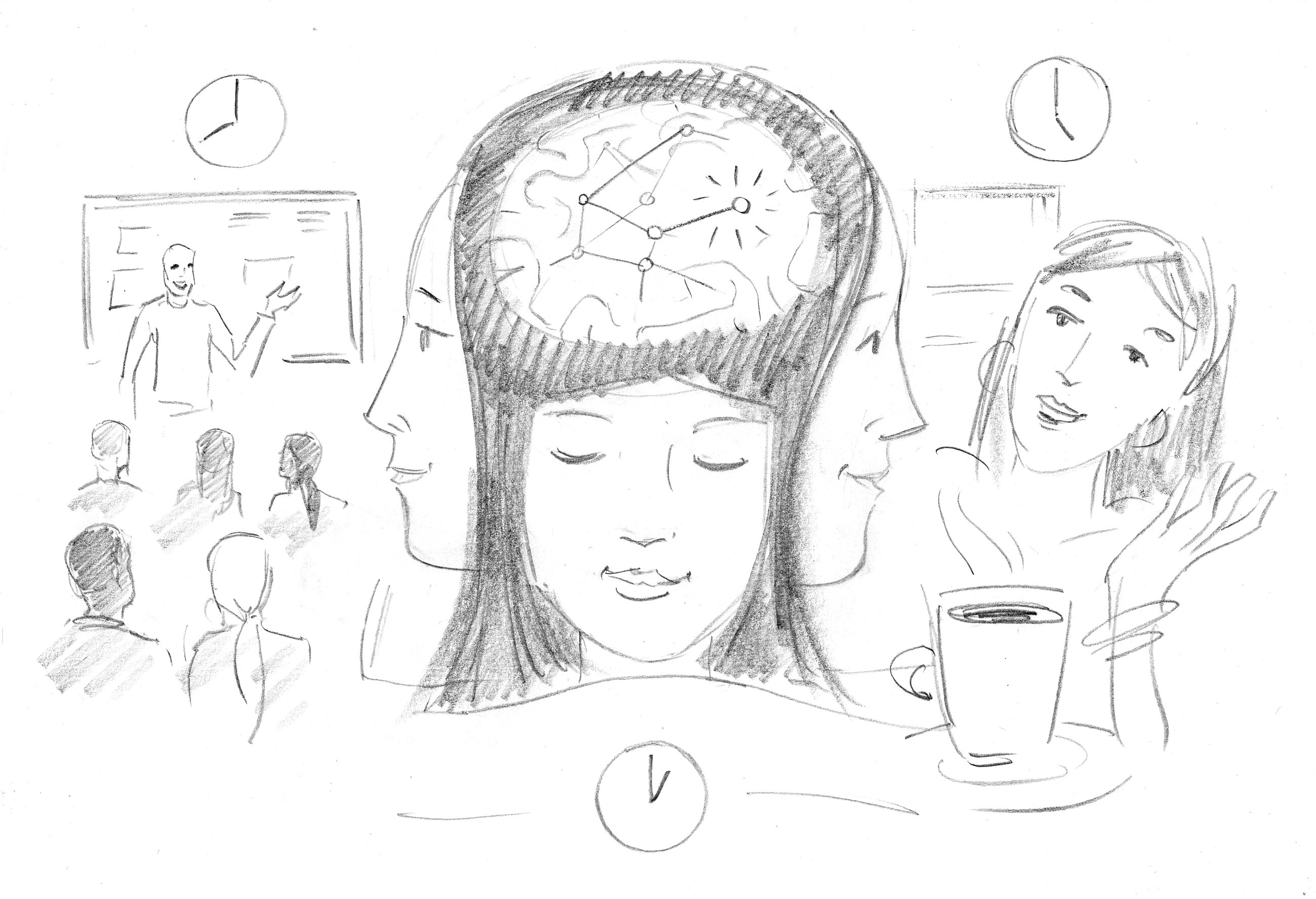

In this way, learning knows no boundaries – it happens all the time. Learning is not happening in classrooms or fixed settings “class by class” but rather “second by second” in real life and natural settings.

As human beings, we have the opportunity to learn in every moment. And we have the chance to make this learning intentional and deliberate – or not. We need to utilise this perspective on learning to a much greater extent to develop our workforce today.

Combatting the “forgetting curve”

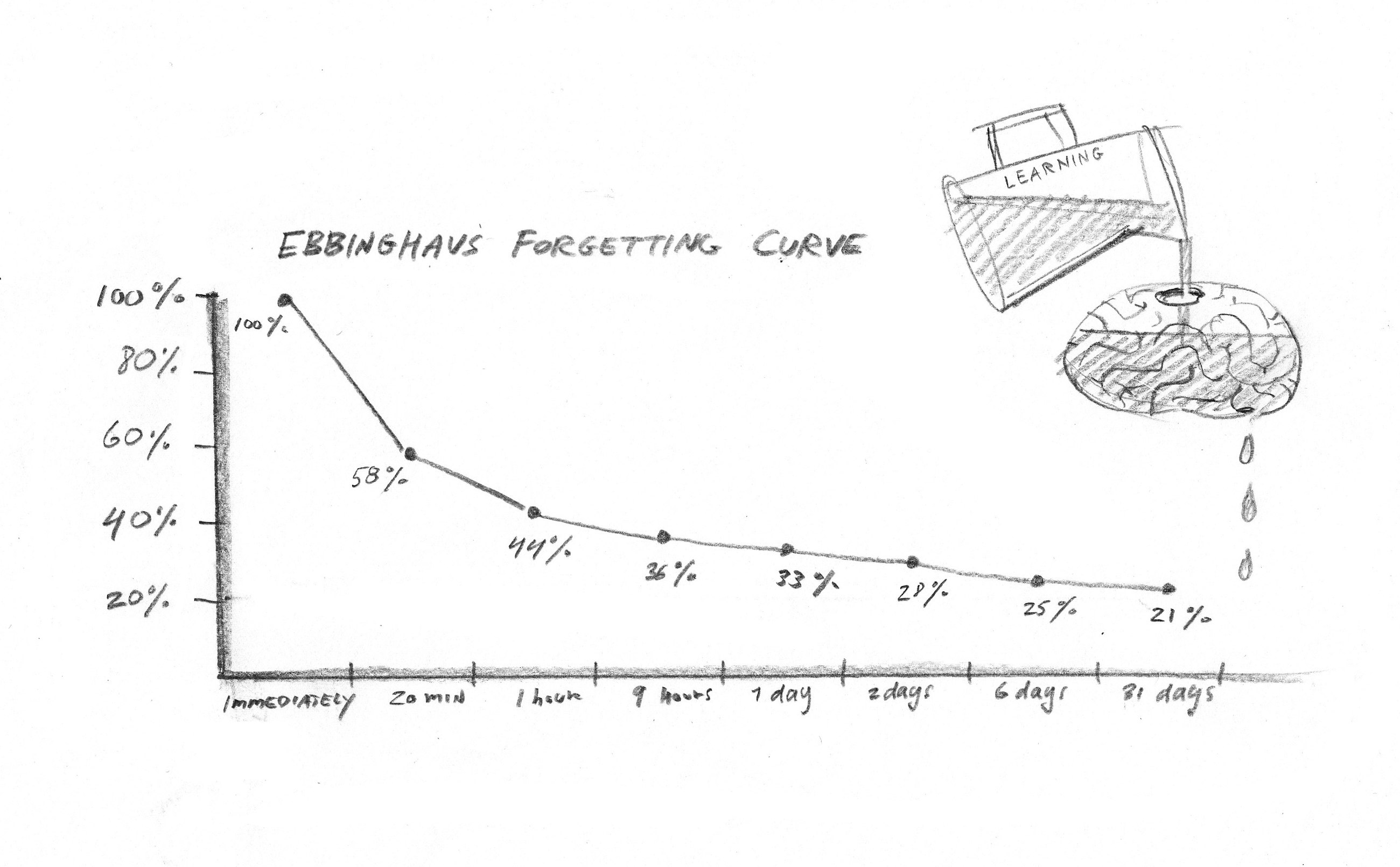

While learning happens all the time, the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve illustrates how easily learning is lost for the individual. The graph illustrates that when you first learn something, the learning disappears at an exponential rate, i.e. you lose most of it in the first couple of days, after which the rate of loss tapers off. A lot of this is due to the context in which the learning has happened.

Today, when we look at best practices and how they design concrete learning interventions, for example, a competence development programme or training, they design the learning intervention on factors that are most likely to combat the forgetting curve.

These factors are:

- Repetition and re-enforcement: More repetitions with “spacing” in between so that the neural networks can be strengthened.

- Focused attention: The simpler the message and the more concentrated attention to it, the better the retention.

- Relevance: The more “hooks” to the learner’s existing world/brain circuits, the easier learning sticks.

- Interaction and generation: The more the learner engages, the better the learning. Research shows that we cannot just absorb information passively. We must take an active, creative role.

- Emotion: Emotions play a dual role in learning. First, they have been found to increase our attention to a given topic which helps us focus. And second, emotions activate a brain region called the amygdala, which seems to alert the hippocampus that the material is important and worth encoding as memory3.

While these factors tell us a lot about the imperatives for the design of concrete learning interventions, another way to combat the forgetting curve is to design learning environments that build on in-situ and experiential learning.

In-situ learning is characterised by experiential learning in real-life contexts as opposed to learning interventions that are associated with traditional teaching in classrooms, away from the contexts in which the learning will be applied. Hence, designing a learning model that is based more on in-situ and experiential learning is a more holistic approach to combatting the forgetting curve.

Three key levers to create learning organisations

Traditional learning models build on the assumption that the organisation knows what learning is needed for the employee to do his or her job. However, in a VUCA world (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity), organisations are more and more dependent on creativity and organic growth, hence, calling much more for bottom-up initiatives and self-directed learners.

We argue that three key levers are key in creating the learning organisations of the future:

A. Foster and support self-directed learning

B. Frame the learning goals in a holistic learning framework

C. Set the right structural and cultural conditions for learning

In the next sections, we will explore these three enablers in more detail.

A: Foster and support self-directed learning

In a situational and holistic framework, learning is something that happens everywhere in every experience. Here learning is networked rather than hierarchical. Such an environment is architected such that motivated individuals, who are driven by a growth mindset and are self-directed in their learning, can thrive and drive the organisation forward.

However, this model can only be successful if it is coupled with individuals who can learn in networked, fluid, dynamic and experiential learning environments. In other words, if it is coupled with self-directed learners.

What is self-directed learning?

Self-directed learners are goal-driven and reflective individuals who have the tools necessary to assess their learning needs and goal setting and seek out opportunities to help them achieve those goals. Further, these individuals can reflect on their learning to help them transfer this knowledge into contextually novel situations.

Self-directed learners thrive in experiential learning environments. In such learning environments, learners go through four stages of learning, including having an experience, a reflection on the experience, distillation of the perceptions that one gains into abstract concepts and then active experimentation with this new information (Kolb, 2014).

Examples of such environments include internships, work-based learning experience, on-the-job training and peer-to-peer learning, simulations, and game-based learning. Each of these learning environments has one thing in common: The learner is acquiring knowledge and applying the knowledge in accelerated cycles where the distance between acquisition and application is very narrow, approximating real-life learning.

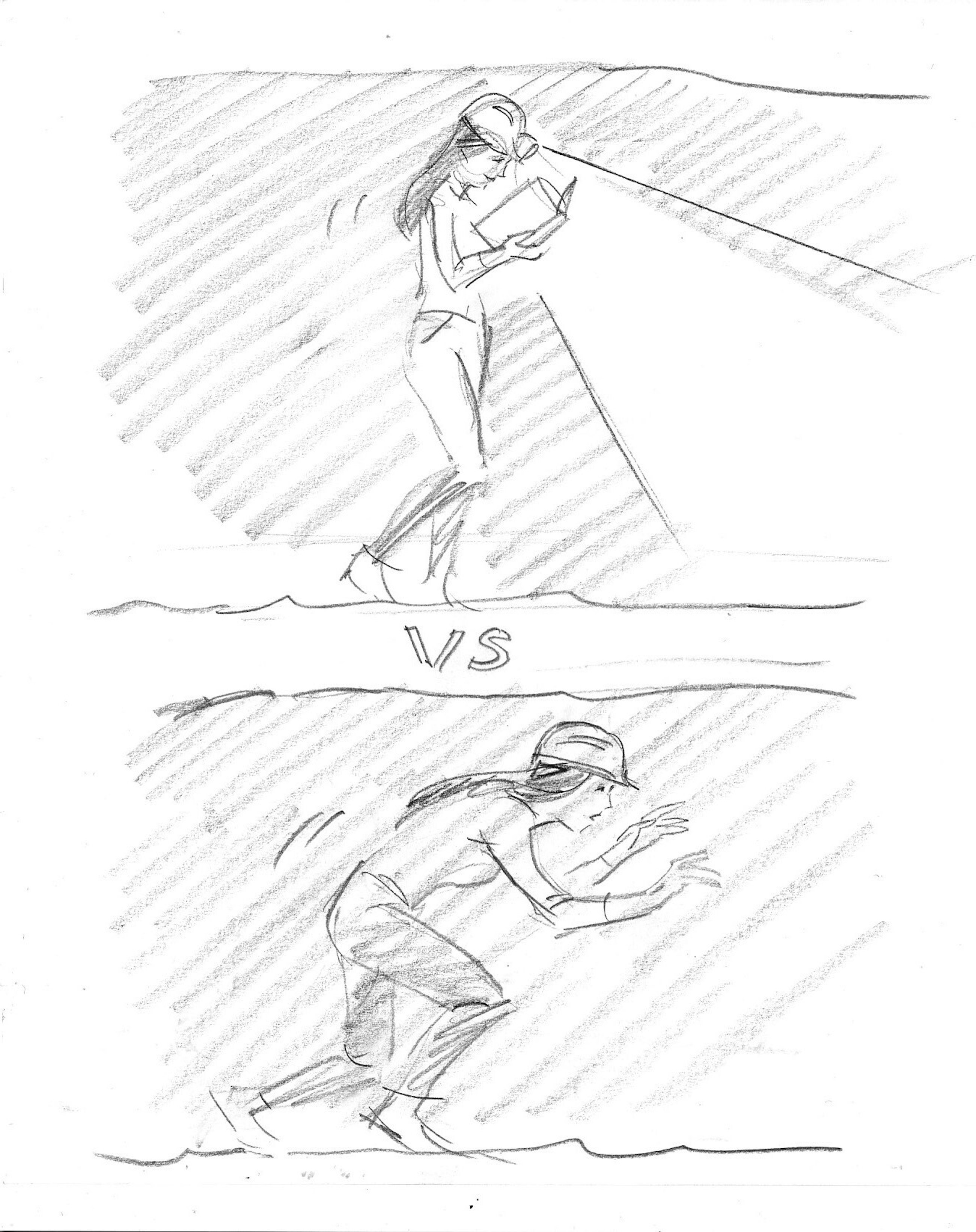

This contrasts with the traditional learning environments where the space between acquisition and application is long. This is not the natural way that learners learn in the real world.

Learning organisations foster self-directed learning by empowering their employees to constantly seek out opportunities for growth and providing them ownership of the success of the organisation. In a learning organisation, these individuals can then be experiential educators of this new knowledge, making the learning environment powerfully generative, building on everyone’s expertise as opposed to an identified few.

But as you might have noticed, to be self-directed, one must be highly motivated to learn. And how do organisations ensure that?

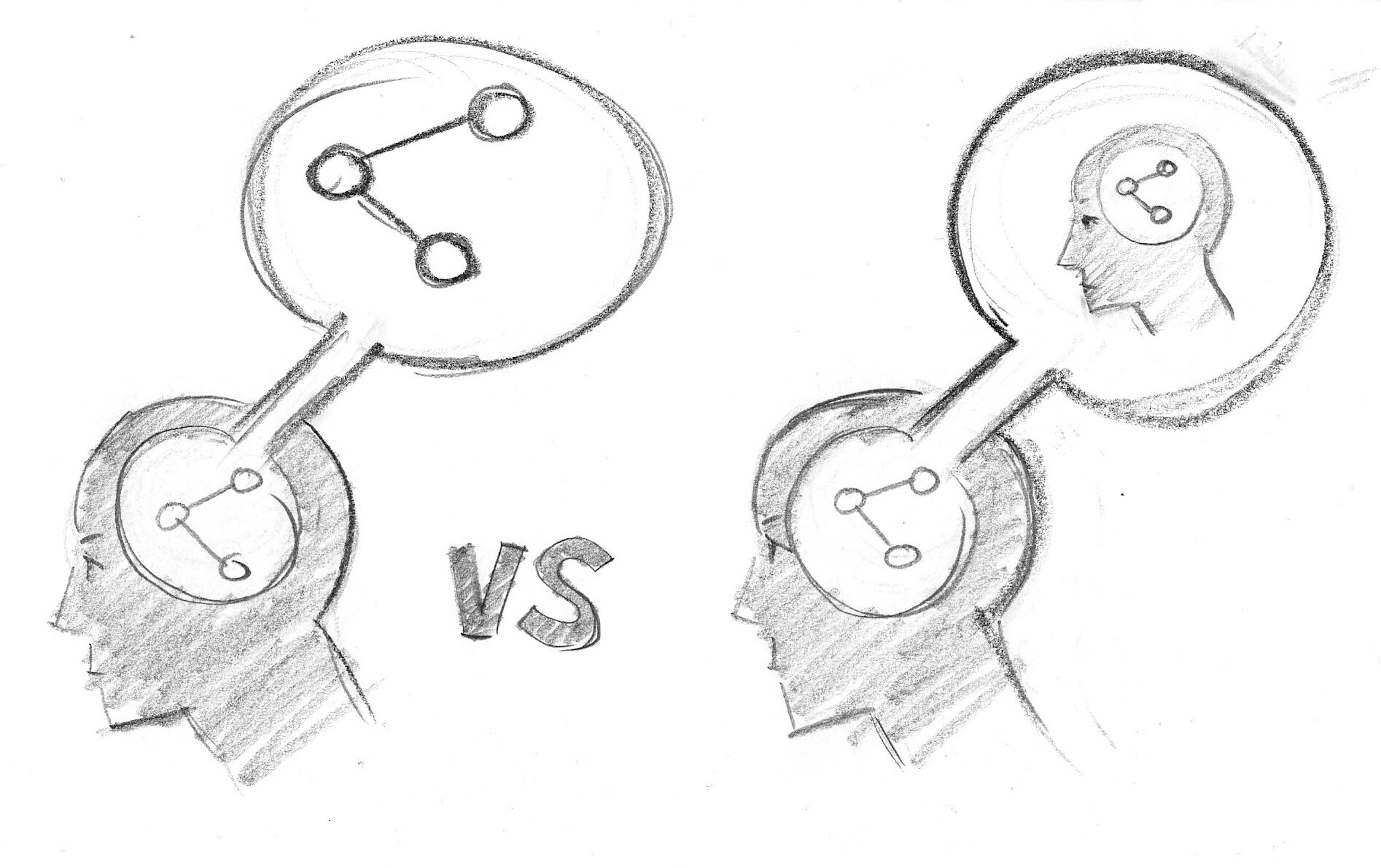

To foster intrinsic motivation and self-directed learners

A crucial point for corporate learning is how it is motivated – top-down or bottom-up? Our drivers (motivators) to learn can be anchored outside (extrinsic) or come from within (intrinsic) – pushed or pulled. When the driver for learning is extrinsic (driven by needs external to the learner), the learning experience is “pushed” on the learner. In situations where the interest in learning comes from the learner, the learning opportunities are “pulled” towards themselves. Such learning is far more robust, lasting and transferrable to new situations as opposed to learning that is pushed.

Motivation is also linked to the learners’ perception of their expectancy of success. The expectancy of success is driven by two variables:

- Outcome expectancies include the learners’ perception that their actions and engagement with the learning opportunity will bring about the desired outcome.

- Efficacy expectancies in which the learners believe that they are capable of identifying, organising, initiating and executing the learning opportunity successfully.

Organisations have significant control over their ability to motivate their employees. In traditional models, where the need for training comes from executives who developed clear performance directives, the motivation tends to be extrinsic with the learning materials being pushed towards the employees. Due to a lack of transparency, it is hard for the employees to understand the value of this training to the organisation and, more importantly, to themselves. Lastly, in the absence of transparency, it is also difficult for learners to assess their expectancy of success.

In a situational and holistic learning approach, the learning opportunities are created bottom-up, a lot of times by peer employees within one’s network. Because the locus of control over the learning is closer to the employee, they have a higher perceived sense of value (for example psychological ownership of the success that comes from their learning) and expectancy of success. As a result, the employee’s centre of motivation is far more intrinsic.

While self-directed learners are autonomous as the outset, their learning in a corporate context still needs direction and framing to be linked to the corporate intention. We argue that they need a clear guiding star and overall framing, rather than a role description and 100-bullet checklist of competences4. And this brings us to the next key lever: framing the learning needs in a holistic learning framework.

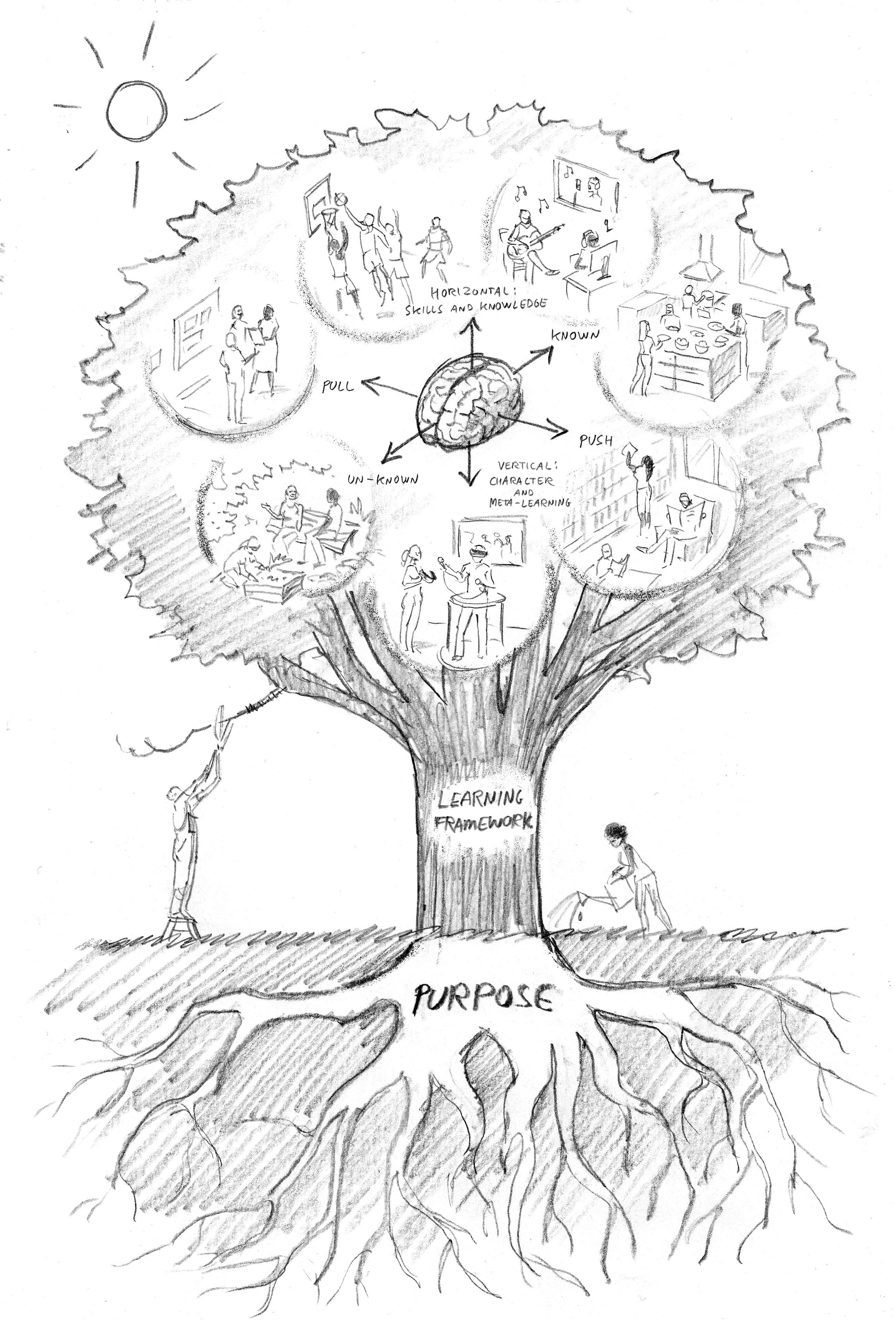

B: Frame the learning needs in a holistic learning framework

As we learn all the time, transparency in direction and framing of the learning needs become key.

But as we just stated, self-directed learners need a guiding star and vision for learners rather than a role description and a 100-bullet checklist of competences.

With such a model, self-directed learners have all the information they need to seek opportunities that might help them develop in a specific competence area or fulfil a certain role. They understand how their engagement in the opportunity develops their learning, and they can assess if the competence has integrated5.

A clear framing of the learning needs in the organisation is the outset of creating an environment where self-directed learners can navigate and flourish.

But what are the learning needs of the 21st century?

Learning in the unknown

When faced with complexity and ambiguity, learning from the past or continuing to build upon existing knowledge does not always work.

We distinguish between learning in the known (learning what somebody else has already defined) or learning in the unknown (learning by doing and solving new things – emergent, explorative and expansive learning).

You can either study what other people have described in books and courses, or you can explore unknown territory to develop new insights, new ways of doing things or new knowledge. Both are learning, and both are of importance.

But when faced with complexity and ambiguity, we need more individuals with competences to navigate and learn in the unknown. And for us to be good at learning in the unknown, it requires a broadening of the competences we value and foster in our organisations.

Learning in the unknown requires capacities and practices such as individual sensemaking, generative conversations and collective sensemaking, collaborations across diversities and functions, comfort with uncertainty and ambiguity, systems thinking and reflective practices.

This shift emphasises a more holistic approach to competences. In practice, this means that when we consider learning activities, we must consider both the expertise-specific knowledge that must be learnt, but also the skills and competences that support the acquisition and application of this knowledge.

Horizontal and vertical learning

In this regard, Dr Robert Kegan, Harvard University, presents a useful distinction between horizontal and vertical learning6.

- Horizontal learning is about developing concrete knowledge and skills – also called subject matter expertise. This covers most traditional functional training at public and corporate universities and academies.

- Vertical learning is about evolving how you think, feel, relate and communicate with others and make sense of the world. It is about increasing the complexity of how you see and relate to the world and to what you know.

Basic skills and subject matter expertise (horizontal learning) will always be relevant. But vertical learning and highly developed reflection and interpersonal skills are becoming more and more critical.

Only a few organisations use an organisational development process that accelerates vertical learning. One of the more famous ones being Google’s pioneering “Search inside yourself” programme7. This programme focuses on mindfulness and self-awareness – subjects that are currently becoming more and more mainstream in corporate life in the 21st century.

A holistic framework for both horizontal and vertical learning

But how do we develop both competences to succeed in the 21st century?

A tangible framework with a focus on both horizontal and vertical learning could be the “Four-Dimensional Education” by Fadel, Bialik and Trilling8. This framework points to four dimensions we need to attend:

- Knowledge – What the employee needs to know and understand. The key here to ensure deep learning is to provide the knowledge in close interaction with exercising the skills. The closer we can come to the actual work, the better.

- Skills – How the employee uses the knowledge. Especially four competences come into focus in the 21st century: creativity, critical thinking, communication and co-operation.

- Character – How the employee acts and engages in the world. The acquisition and strengthening of personal qualities, values and capacities to make sound decisions for themselves and society. In today’s world, knowledge and skills are far from enough to handle modern challenges. Fadel, Bialik and Trilling suggest that we need to supplement with six qualities: mindfulness, curiosity, courage, resilience, ethics and leadership.

- Meta-learning – Learning-to-learn focus on the employee’s self-reflection and autonomous approach to continuous learning. Meta-learning further develops the employee’s second-order perspective on knowledge, skills and character and strengthens the use of these in other contexts.

By incorporating all four dimensions in our corporate learning models, we can help the employee to learn and grow on both the horizontal and vertical axis to better handle and navigate in the unknown and meet the challenges of the 21st century. Now, let’s turn to our last key lever to enable a situational and holistic framework for learning in organisations.

C: Set the right structural and social conditions for learning

Building on the fact that learning happens all the time leads us to look at the organisational conditions that either support or create a barrier to learning in everyday life. Such conditions for learning include both structural and social aspects:

Structural conditions for learning in a corporate setting

- Physical setting: workplace design and how it allows learning and encourages creativity, curiosity and collaboration. This also includes basic things such as daylight, availability of food, sound etc.

- Processes and how they include time for continuous learning loops, reflection and feedback.

- KPIs and how they reflect learning and development in the short and long term.

- Organisational design and how it enables sharing, communication and experimentation.

- Digital infrastructure and information availability and how people are empowered with knowledge when and where they need it.

- Brain-friendly learning offerings – making it easy, fun and rewarding to learn and train new skills at work

Social conditions for learning in a corporate setting

- Values that reflect learning and development.

- A culture that establishes all members of the community as both educators and learners.

- A culture of peer-to-peer sharing and support.

- Social routines and how they support learning.

- Internal communication and how it drives direction, sensemaking and importance of continuous learning.

- Diversity.

- A culture that supports psychological safety.

From “fill me up with knowledge” to “water my roots so I can grow”

Creating such conditions for learning is like fertilising the soil for learning with the mindset of a gardener, rather than a petrol station attendant filling on petrol. This means a shift in how to work with learning from “fill me up with knowledge” to “water my roots so I can grow”. We believe that the learning gardener mentality will be the key role for future learning leaders and capability builders.

This moves us away from a narrow focus on managing course catalogues and designing course materials and PowerPoints. Instead, we will communicate direction, frame the overall learning goals (learning framework) and foster generative conversations across the organisation to enhance collective sensemaking and learning practices. We will identify barriers to and enablers of learning and design, test and scale “hacks” and solutions to support learning in-situ.

While this form of thinking is not new, the world is still short of good examples of putting the thinking into practice.

At Northeastern University, they have reinvented their learning approach and embraced this new paradigm, inspiring other Universities and corporates.

Fostering self-directed learning at Northeastern University9

Over the last few years, Northeastern University in the United States has begun to broaden its already successful experiential learning model. They now prepare learners to leverage the learning opportunities that abound around them, both inside and outside the classroom. This includes learning in their programmes of study, but also through their contributions in clubs and organisations, volunteer work, co-operative education opportunities (i.e. work-based learning opportunities) and athletics, to name a few. This is all to prepare their learners to be able to leverage learning opportunities that will present themselves once they graduate.

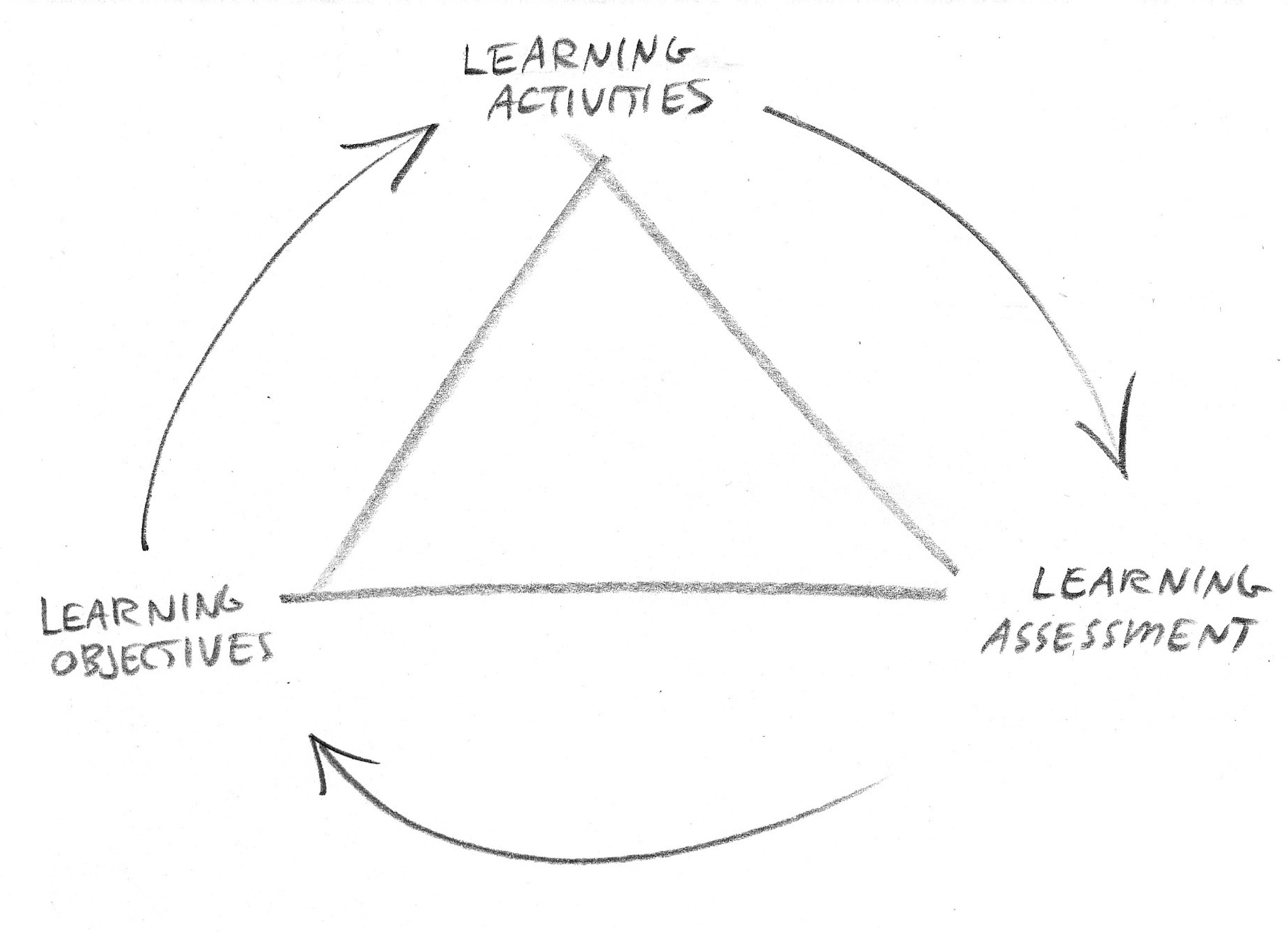

The SAIL (Self-Authored Integrated Learning) is a platform that anchors learning for students at the university through a holistic framework that reflects a lot of the vertical learning described above. This platform digitises the experiential learning process to scaffold self-directed learning and prepares learners for a life of learning through experience as opposed to traditional learning environments. Through the platform, learners can engage in all phases of constructive alignment as well by creating goals and identifying opportunities with learning outcomes to achieve those goals. They can reflect on the learning as a result of their engagement and understand how that impacts their growth and leads to future self-directed and identified opportunities for growth.

Northeastern University is not the only university to start to rethink how higher education approaches learning. In other words, universities are looking for more and more opportunities for their students to learn through real-world experience, while corporations are still taking their learners/employees out of this very environment for development.

Bringing it all together

Learning is more important in corporate life than ever. However, current learning models need to be challenged and refined to deliver value. This starts with a deeper and more granular understanding of what learning is, leading to a more holistic and situated approach to learning.

Applying such an approach at the organisational level entails developing an environment where learning is fostered through the creation of robust learning environments. Here learning is advanced everywhere, and everyone has the potential to be a learner and an educator.

To make this possible, the corporation must provide direction and frame the overall learning goals for the organisation and its holistic learning framework. This will serve as the map upon which individuals across the organisation can situate themselves and identify areas of expertise (where they can be educators) and areas of growth (where they can engage in self-directed learning).

Further, such an organisation must balance the push of knowledge with creating the optimal conditions for pull-based learning to happen.

We would suggest any leader or person responsible for learning to consider the three key levers to enable a situational and holistic learning culture for their organisation:

- Foster and support self-directed learning.

- Frame the learning needs in a holistic learning framework.

- Set the right structural and cultural conditions for learning.

The way to do this will vary from organisation to organisation and be highly context-dependent. This is calling for leaders and HR professionals to experiment and innovate interventions to create just the right ecosystem for them, rather than copying “best practices” and standard solutions.

This work can start from many angles with small tweaks or large interventions. In any case, the best “learning gardeners” will create an important competitive advantage in creating true learning organisations.

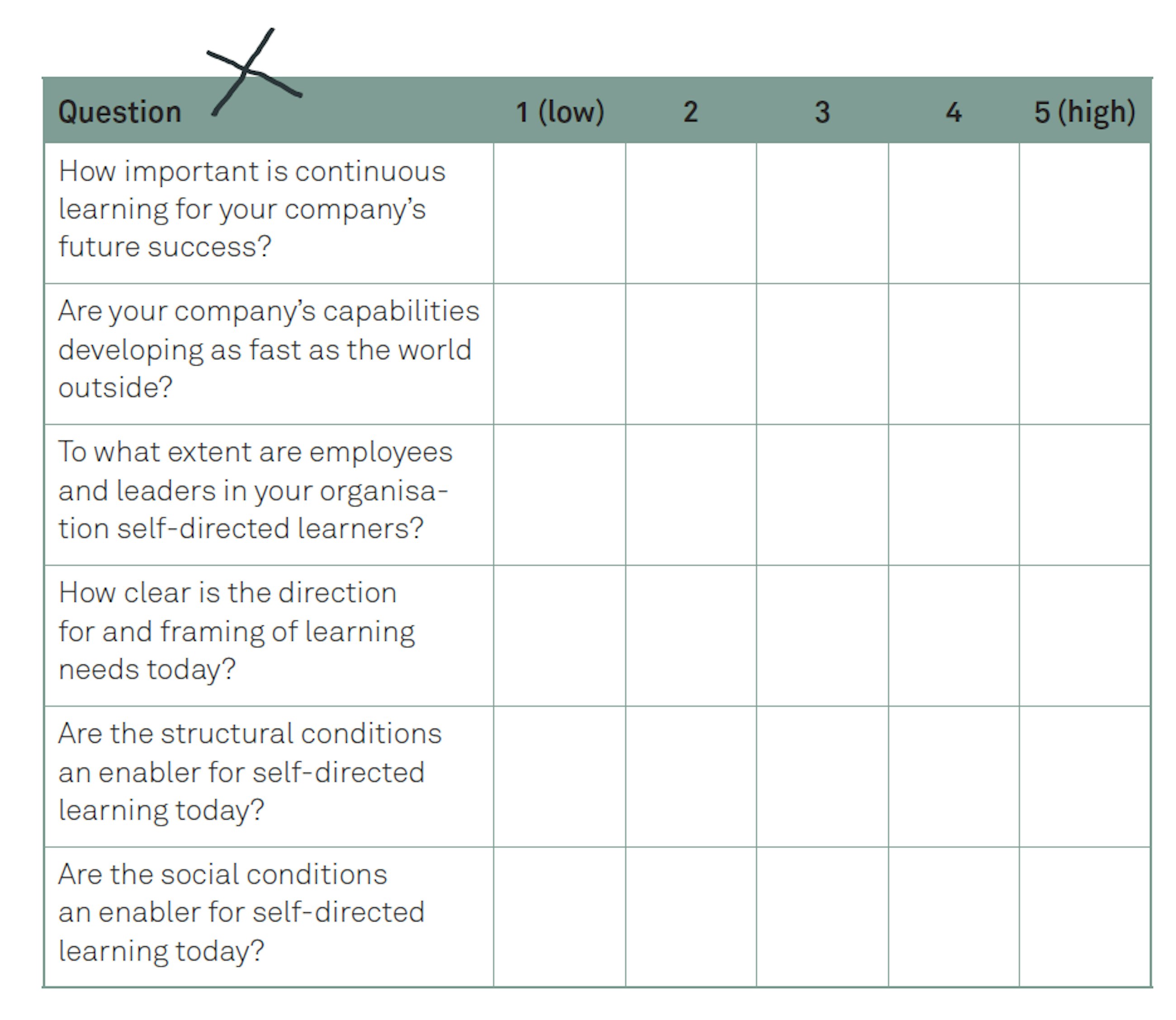

Self-assessment: Are you working in a learning organisation?

Most organisations today are making efforts to come closer to be a learning organisation. Building on the points from this article, some key questions to ask on this journey would be:

References

1 implementconsultinggroup.com/future-business-trends/

2 hbr.org/2019/10/where-companies-go-wrong-with-learning-and-development

3 growthengineering.co.uk/improve-retention-online-learning/ and neuroleadership.com/your-brain-at-work/ages-model-for-learning

4 For further reading on competence models, see: implementconsultinggroup.com/media/4869/four-dogmas-for-creating-powerful-compenetcy-models.pdf

5 Constructive alignment (Biggs, 1999)

6 Kegan R. and Laskow Lahey, L. (2009). Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization. Harvard Business School Publishing: Boston.

7 businessinsider.com/search-inside-yourself-googles-life-changing-mindfulness-course-2014-8?r=US&IR=T

8 Four-Dimensional Education: The Competencies Learners Need to Succeed.

9 sail.northeastern.edu/about/

Illustrations by: Sune Elskær