11 September 2019

Getting people to act differently is a complex task. Often unconscious, behavioural patterns save our brains important energy, and thus changing behaviour can feel tough. By using behavioural design, you can design practical strategies that help people master the tiny behaviour patterns that lead to behavioural change.

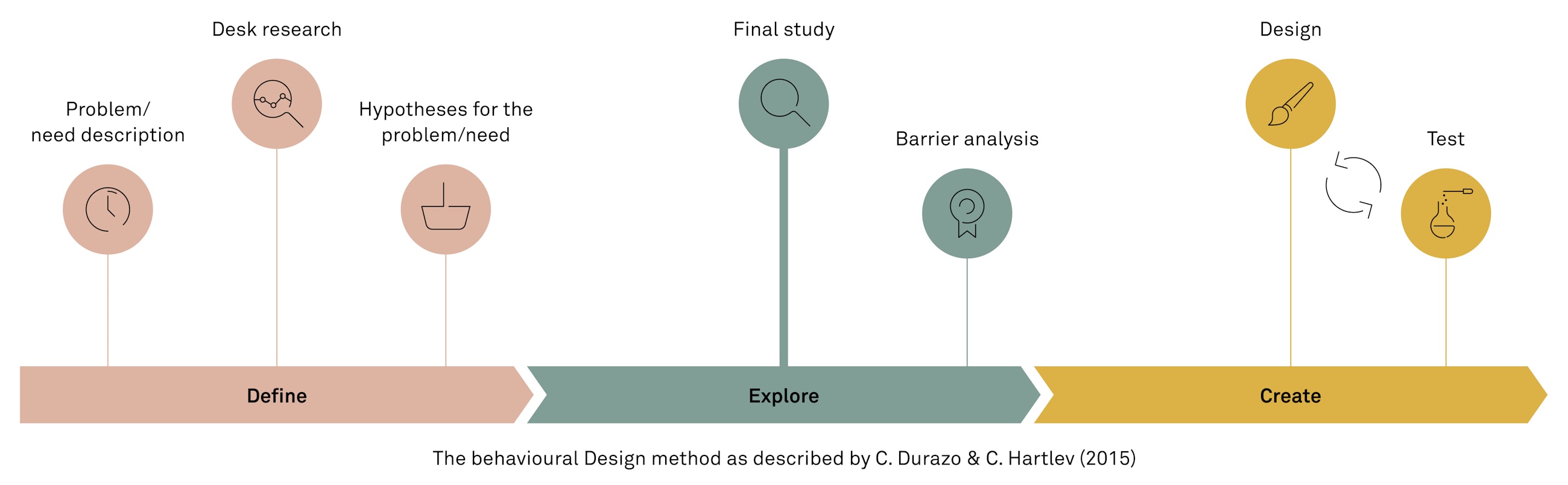

Behavioural design is a method designed to make you focus on humans as the core of your solution design. It does so by applying a still expanding field of behavioural sciences with data and validated design tools. Whenever behavioural design is at the centre of the conversation, two things come up – the discussion of mindset and the concept of habits.

In this article, we want to focus on these two central aspects of behavioural design.

- First, we hope to uncover a mindset for approaching change when looking to change behaviour.

- Second, we want to address the exciting and mysterious concept of habits and how we work them.

Thank you for making it this far. Let us begin.

1. Curiosity: A mindset for approaching behavioural change

Behavioural design is (like many other concepts) at risk of becoming the new faddish concept of change. The method is receiving immense popularity today, but we are yet to see whether it becomes an integrated part of future change in organisations.

It is important to note that just because small plates, tax collection letters framed by social norms and footprints next to a litterbox may seem like easy-to-replicate designs, it is the methodology and mindset that will keep behavioural design from turning stale and hollow.

Thus, it is time to take a pledge before moving on:

I will stay curious!

When you decide to work with human behaviour, you decide to work with one of the most fluctuating and heterogenous entities. Human behaviour cannot be generalised, and it will not be turned generic.

Although we now have scientific formulas for habits and decision-making, it is still in the state of e.g. being drawn to the smell of new car that we must acknowledge that what drove the emergence of these insights is the same thing that will make sure we develop organisational change in the future. We need to stay curious towards the real world before we define our solutions.

To gain insights, we strike upon an important law for many behavioural designers: You do not know anything unless you have the data to back it.

Data is to many what the likes of Google Analytics provide; an extensive dashboard of graphs flows up and down, somehow unveiling a pattern that is predictive of future behaviour and for sure descriptive of the behaviour that is. But data is so much more, and we can get a long way just by looking into studies, google what others have done or merely walk out of the comforts of our office and observe, ask and take notes.

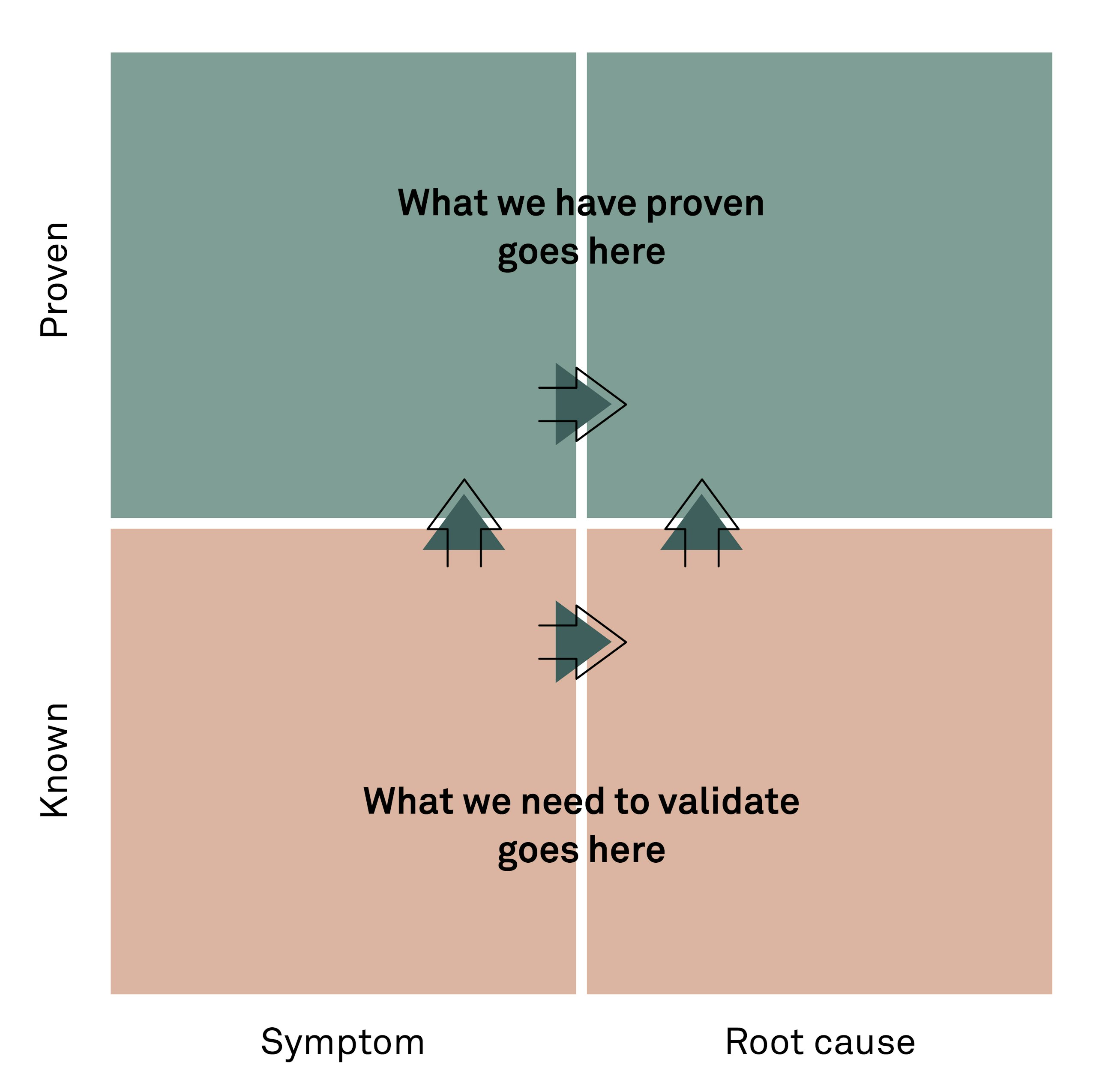

You can get an overview of the data available and the data you need by mapping your knowledge. This gives you a clear overview of what additional data you need and what is already proven. The purpose of the exercise is to make it obvious to you and your team that not everything is known. Also, by mapping your knowledge, you challenge the crucial assumptions about the field you are about to change, which can only lead to a better solution design at the end.

Staying curious not only means that you stay curious about your target audience and context, it is also to stay curious on your own ways of working. We talk about the bias blind spot, which is the tendency to see oneself as less biased than other people and being able to identify more biases in others than in oneself.

By this notion, behavioural design has been developed to not only work with the behaviours of others, but also with the behaviours of your team applying the method by forcing you to challenge your assumptions through the field study and data collection phases.

2. The habit intervention

Often when we bring up behavioural design, habits become the conversation topic. We so badly want to change our own habits or the habits of others – and we want to do it quickly! But there is a problem. Even though the likes of Charles Duhigg, Marshall Goldsmith and James Clear have described the habit equations and studied how habits change, they all agree on one thing: changing habits take time!

According to James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, a new behaviour becomes automatic after 66 days on average. This means that your body has now learnt the movements or thought processes by “heart”, and you no longer need to strain to perform it. Now for this to become a habit, it will vary from an additional 18 to 254 days, so expect a habit to form somewhere between 2 to 8 months after having started the change.

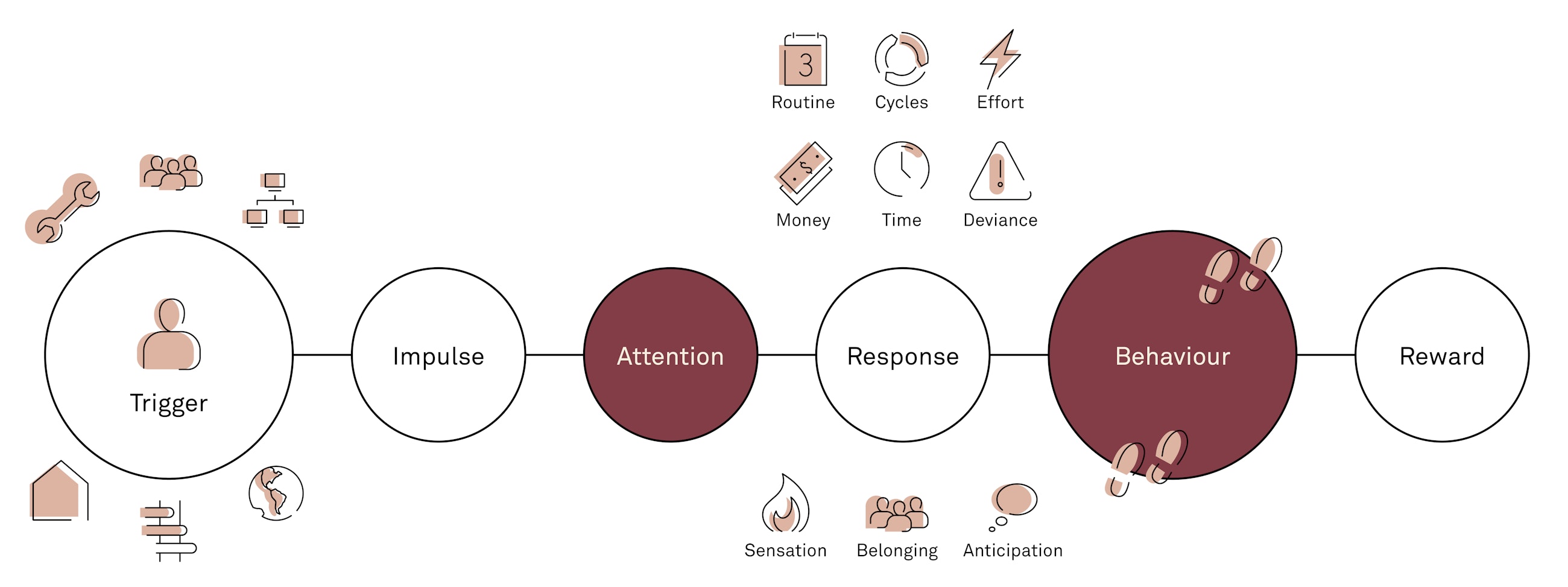

It may seem like a long time, but in organisational change, we do not necessarily need a habit to be the success criterion. All we need to do is to apply the script for habit building to make new organisational behaviours easier to adapt to. The reason is that the organisation is a sandbox. It is a closed area where we move between spaces of predefined functions, and we tend to engage with the same people and technologies throughout the day. So, remember this the next time you want to work with habit change:

If motivation is the fuel to start the change, the trigger is your catalyst sparking the behaviour that uses the fuel. Triggers can succeed in many ways, but only if it is timed correctly.

A trigger is seldom considered a piece of information, where a management email clearly states what you should do next time you have your 1-1 feedback session with a colleague, or a billboard tells you to remember to put the organic trash in the little green bin along the sidewalk. No, the trigger is placed much closer to where the behaviour occurs. So, in the mentioned cases, the trigger is your agenda for the meeting or the actual trash bin placed in obvious locations where organic littering most often occurs. To put it in the words of James Clear:

“Environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior. We tend to believe our habits are a product of our motivation, talent, and effort. Certainly, these qualities matter. But the surprising thing is, especially over a long time period, your personal characteristics tend to get overpowered by your environment.”

So, when engaging in a new behavioural change, keep in mind that information alone won’t cut it. You must be a designer of the environment where the critical behaviour occurs. This environment is only for you to design if you have made an effort to understand what it consists of and what it is you need to change in order to direct new behaviour with well-timed triggers.