New patchs to creating growth and delighting customers

4 October 2012

We are involved in a project for a global growth company where we have recently carried out a project with focus on developing products faster and more efficiently. The project was, in our opinion, a success.

The client company, which is recognised as one of the world’s leading experts within their area of expertise, was, basically, satisfied. However, because they act the way they do when clients are at their best, they ask anyway: Seeing that we are capable of reducing the lead time of a project from 600 to 300 days, why not reduce it to 100 days?

Why not?

It is, of course, quite the party-killer in a situation where we had expected to get a pat on the shoulder for our efforts. But he is right. Why do we consider good results as final when we are fully aware that in 12 months from now, we will be able to create the same percentage improvements one more time and once again 12 months later? Why do we not change our mindset radically, raise the bar and reap the full benefits now? And once again – not in 12 months, but in six months?

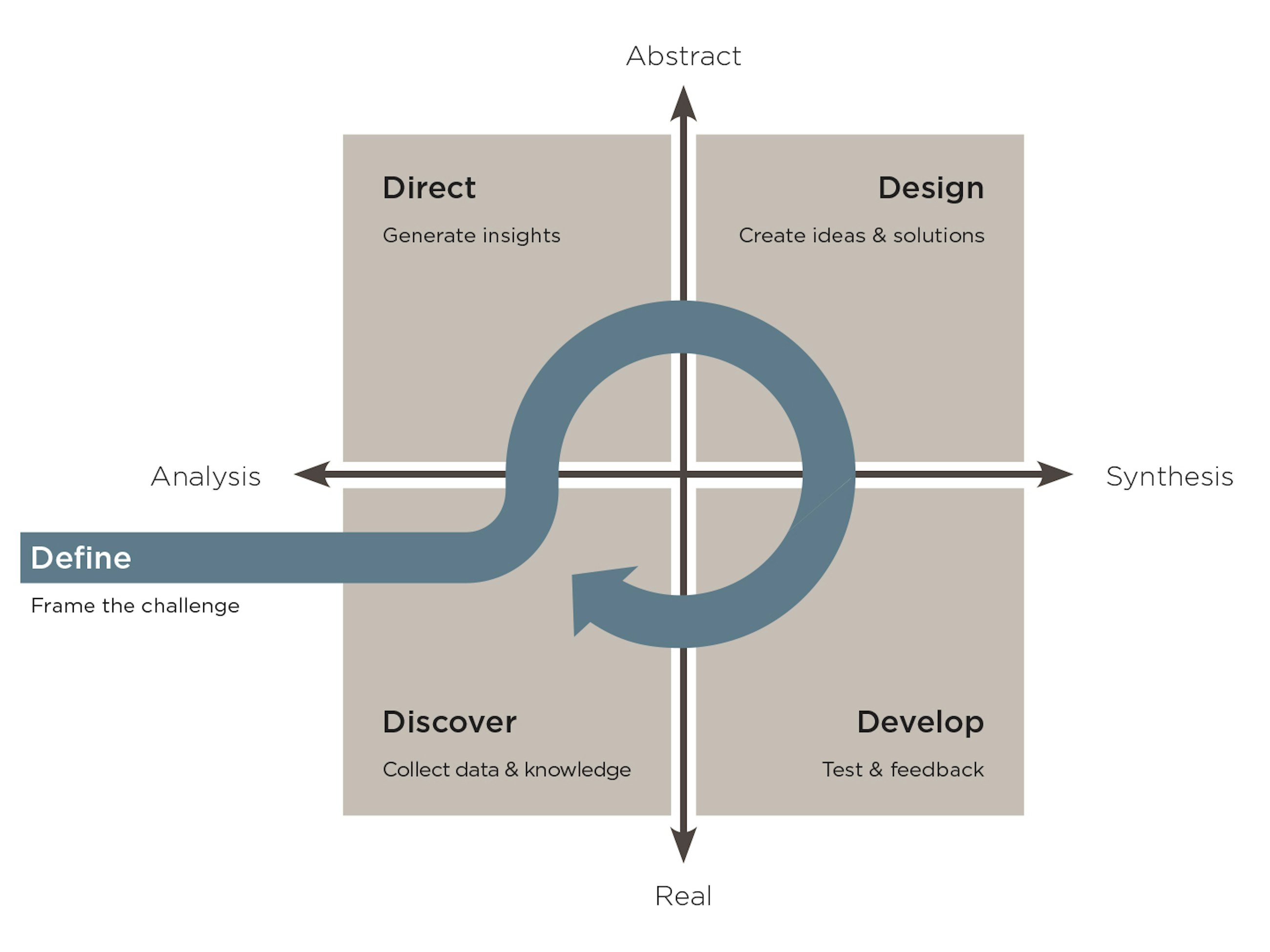

Recently, we had the pleasure of discussing strategy with Roger Martin, Dean of the Rotman School of Management. According to Martin, today, most strategic work suffers from a gap between analytical and intuitive thinking. This is primarily caused by the fact that strategy has become an analytical discipline where predictability is rewarded more than results. Rather promise little and surprise positively than reaching for the stars and risking not quite reaching them – analogously to the above example.

However, large innovations solely based on analyses of the past are rare. For even though the analysis is imperative in order to being able to understand and generalise and, thus, scale, the tempo and complexity in our surrounding world have reached a level where we need to change the balance between value creation and our need for predictability. Those of us who think analytically must learn to speak an intuitive language, and those who think intuitively must learn to communicate in an analytical mindset. Both sets of competences are absolutely necessary. Even though innovation and intuitive thinking are closely linked, it is only when rationality and analysis are involved in the process that the large-scale commercial and business breakthroughs take place.

Companies such as Apple, Google and Just Eat are good examples. Their development has been unpredictable, but their value creation has been immense, because they have been able to combine intuitive and analytical thinking. Whether we, as Roger Martin, call it Design Thinking is of minor importance. We MUST be able to combine that which is rational and analytical with that which is intuitive and irrational. In this cross field, limitations turn into opportunities. This is also where the most successful companies operate and the best employees thrive, develop and generate most value.

Thus, the question presented in the beginning of this article is just a logical consequence of the reality we live in and a question that we – who are well on in years – must get used to being asked: Why not? ...

Understanding the why, what and how of business model innovation

Short-term competitive advantage is created by exploiting existing business models. However, in the long term, all markets mature, competition intensifies and turbulence increases. Consequently, new sources of growth must be explored, and fresh answers to enduring success must be found. The answer used to be innovate or die. But research shows that pouring more money into pure product innovation does not lead to improved performance. We need to dig deeper.

To succeed in innovation and to seize new opportunities, the scope of innovation must be expanded to encompass the full business model, and new processes must be mastered. This article explores how an innovative business model is linked to customer value creation, defines growth opportunities and presents key success factors to exploit the potential of business model innovation.

Rethink customer value creation

Delighting customers is the heartbeat of every business

While pundits claim that the only constant in the world of business is change, one factor remains unchanged and stable. At the heart of any business should lie the aspiration to delight customers. It might seem deceptively simple, but, in reality, this core tenet is challenged every day.

What is customer value?

The idea of ”delighting customers” can be translated into the equally simple idea of ”creating value” for customers. But what exactly is customer value, and how can it be defined?

Firstly, customer value cannot be equated with low price. More precisely, value creation is a trade-off between certain benefits and costs associated with the value proposition over its entire life cycle. The total value of ownership must be calculated to assess the value creation potential.

Secondly, value lies in the eye of the beholder. Value is subjectively judged by the customer, which means that we must identify perceived benefits and costs. All insurance companies know this fact as they, in reality, sell products which, hopefully, are not used. Value is not related to product attributes, but rather customer benefits.

Thirdly, the value creation potential must be adjusted for the riskiness of the value proposition. All innovators know this by heart. New products that are relatively unknown are always harder to sell than well-known products because of a higher perceived risk.

Taken altogether, customer value can be expressed as:

Customer value = (perceived benefits – perceived life cycle costs) x (1 – perceived risk)

Outside pressure from investors triggers the desire to focus on short-term optimisation putting long-term customer and, thus, shareholder value creation at risk. Diverse stakeholder groups compete to capture attention and influence key decisions through rhetoric or regulations. Inside impediments come in many shapes. Actions of the past such as investments and strategic choices create commitments that are hard to escape when customer needs are changing. Often, the understanding of customer needs lacks depth or is based on false assumptions, thus limiting capabilities to conquer a differentiated position in the marketplace. Management incentive structures are aligned with a strong focus on ”running the business” rather than ”developing the business”. Mental blinders tend to pop up resulting in a bias to run business as usual, and new ideas are judged unattractive due to the risk of cannibalising the current business. And the list continues.

Altogether, the simple goal of delighting customers is not that simple at all. Even though it has been proven time after time that customer-centric organisations are the most successful, it is complex and challenging to walk the talk. Moreover, the ways in which organisations deliver valuable customer experiences have dramatically changed in the past decades.

Focus on customer benefits – not product attributes

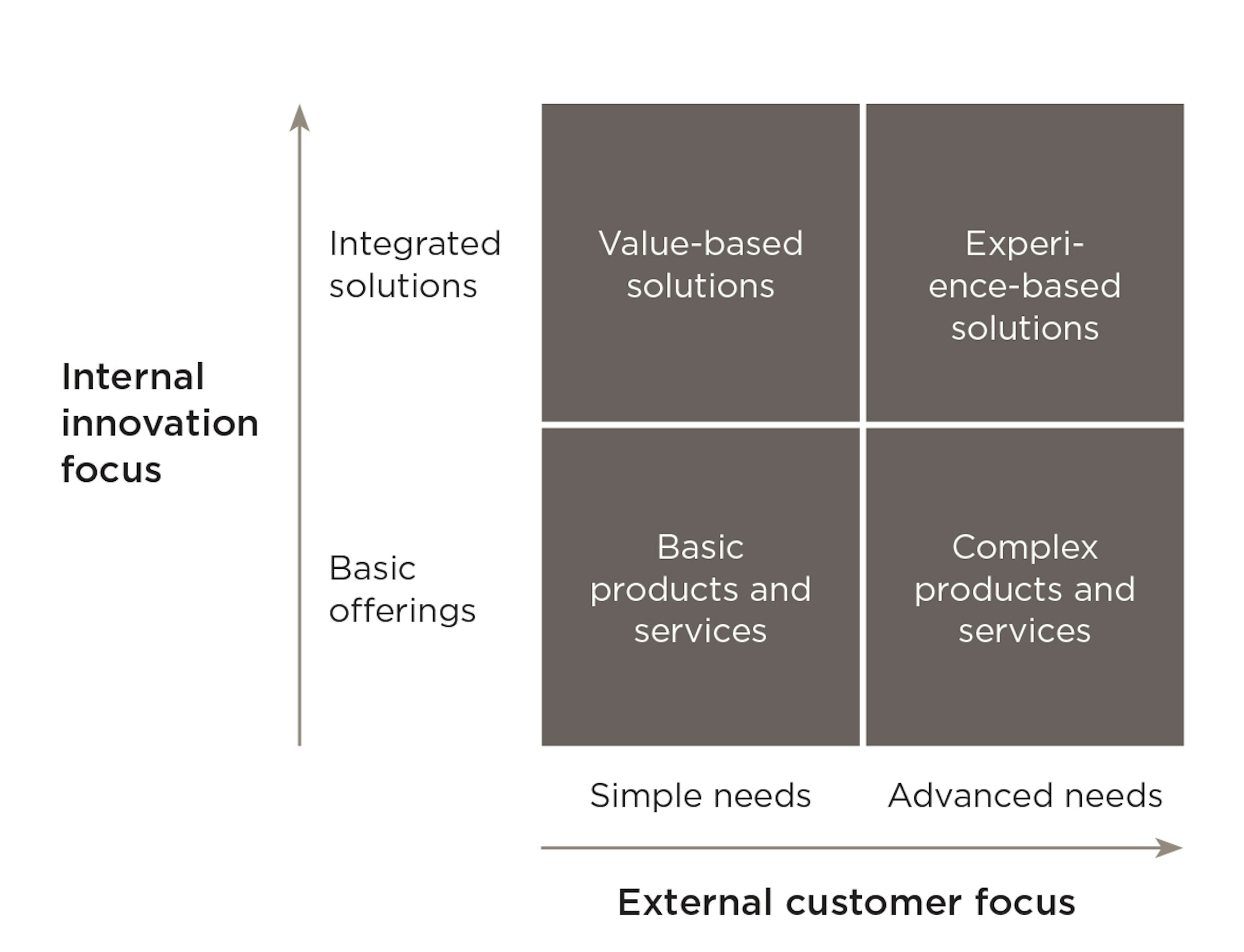

A quick glance at the history of delighting customers shows that focus has expanded from fulfilling simple needs to addressing the full range of advanced customer needs, and the scope of innovation has been widened from basic products to integrated solutions. In other words, the key driver has been growing attention to manipulating all parameters of the business ecosystem in order to deliver customer value.

In the days of mass production, customers were delighted by simple products fulfilling basic needs and wants. Henry Ford famously dictated in 1909 that customers could have the functional benefits of his Model T, while he cared less about fancy colours: ”Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black”. Cars were black and nothing but black.

However, excess post-war production capacity and a frugal culture created the perfect storm, motivating companies to find new ways of reaching the heart of their customers. Increasingly, generic products were differentiated and associated with emotional and social benefits. The rise of branding and segmented marketing strongly indicated a shift towards a broader concept of customer value creation. The shift is beautifully portrayed in the TV series Mad Men about the American flourishing advertising industry in the 1950-60's and the boom of Madison Avenue ad agencies.

Who is your customer?

Simple questions usually turn out to be tough ones. Theodore Levitt asked: ”What business are you in?”. We also need to ask: ”Who is your customer?”. While the examples mentioned show the importance of the end user, value creation should be managed for all touch points that your offerings have before reaching the final customer.

In the insulation industry, Rockwool has analysed and designed value propositions for all customers involved with their core product. The chain of customers includes building owners, architects, contractors, sub-contractors, installers and distributors. Moreover, a careful evaluation of different segments within each customer group needs to form the basis for the design of different value propositions for every group.

In the case of fast-moving consumer goods, all companies face similar challenges. Value creation cannot only focus on the end consumer, but should also consider the needs of the shoppers buying the goods, the retailers selling the goods, the wholesaler distributing the goods and even external partners responsible for production. Before pouring a simple glass of milk, customer needs must be served appropriately many different places in the total consumption chain.

In parallel, the strong focus on tangible products was replaced with the idea of comprehensive value propositions and selling total solutions to customers. Solution selling emerged as a discipline in the 1970s and is still an effective approach to customer-centric sales. In fact, many businesses are still on a journey from delivering products to creating solutions composed of both tangible products and intangible services. The trend has also been dubbed servitisation of manufacturing, which also highlights the shift towards designing all aspects of the customer experience as well as tailoring the experience to individual customer needs. Customer delight was no longer perceived as a result of simple products, but integrated solutions with a carefully designed and value-adding layer of experiences that surrounded the core product.

In the 1990s, Joe Pine and Jim Gilmore portrayed the rise of the experience economy in which they claim that work is a theatre and every business a stage. Accompanied by branding strategies that engaged all five senses and even experiences designed around the idea of catalysing personal transformations, the experience-centric thinking supplemented past logics of value creation. On the one hand, products developed into solutions. On the other hand, fulfilment of functional needs was accompanied by addressing more sophisticated customer needs.

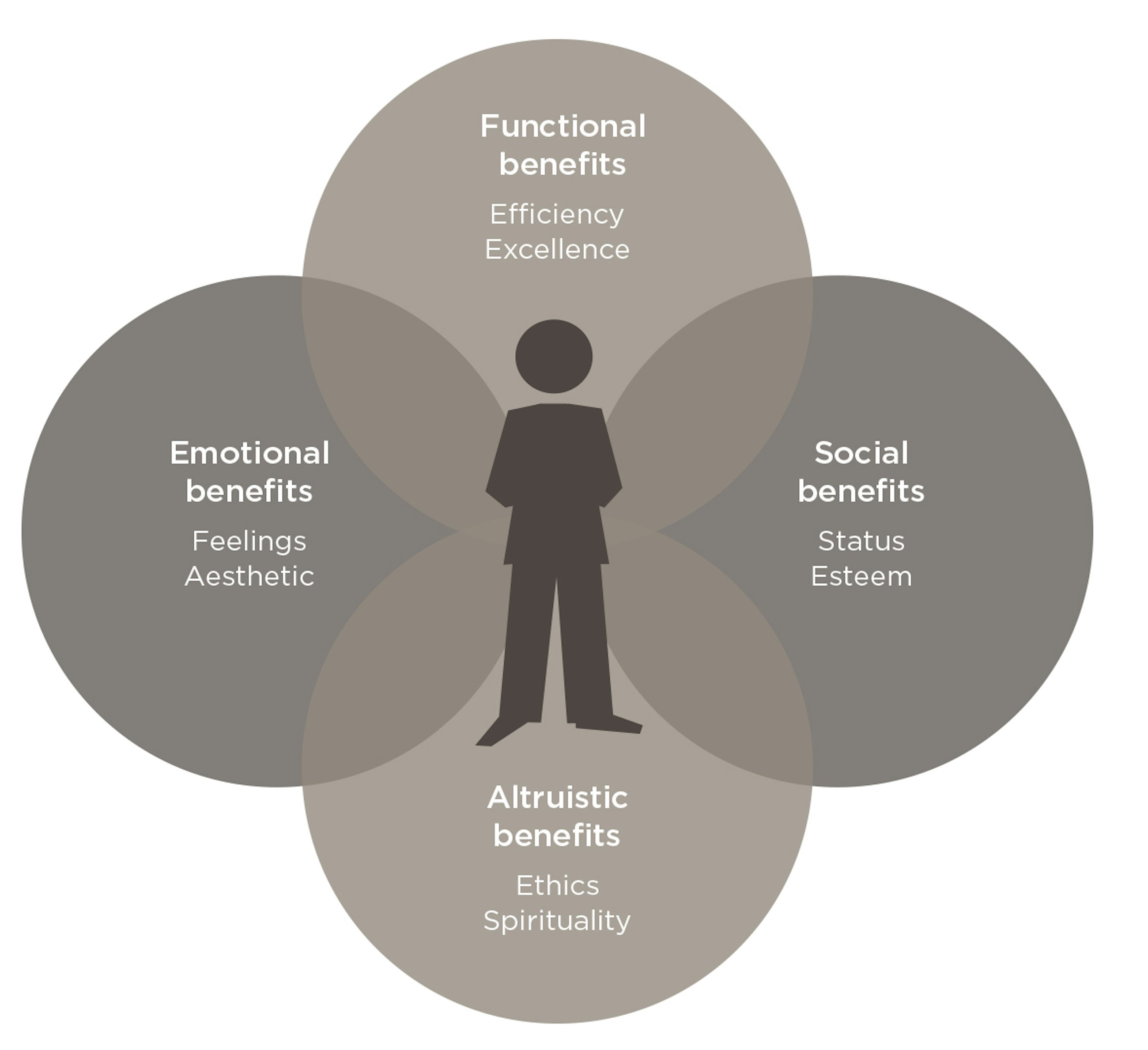

Recent developments in the ways of delivering customer value might be considered as a counter-reaction to the mainly narcissistic attempts to achieve experienced-based differentiation. Fuelled by financial meltdowns, rising awareness of human impact on the environment and increased global inter-connectedness, most organisations are now consciously evaluating how to fulfil altruistic benefits for customers. In other words, how to incorporate elements of selfless concern for the welfare of others in their value propositions, e.g. cradle-to-cradle principles and the ambition to safeguard the planet for the coming generation through company-wide social responsibility, plays a still more vital role in order to delight customers (figure 1).

Develop experience-based solutions to gain competitive advantage

As a consequence of increasing competition in mature markets, new opportunities in emerging markets and near-constant disruptions at the fringes of most industries, focus on delighting customers plays a key role in gaining a foothold in a competitive marketplace. Although the notion of creating blue oceans is appealing, real-life experience often shows that competitors quickly invade uncontested space and capture market share.

To carry on delighting customers on a continuous basis, advanced manners of delivering value and creating competitive advantage are needed. Add to that the dramatic consequences of recent technological developments such as the internet that has created an unprecedented range of opportunities to interact with and deliver value to customers. By leveraging the power of emerging technologies, entirely new markets have been made accessible, and novel manners of interacting with customers have been created.

Consider Danish telecom TDC that bundles telephony subscriptions with free access to millions of music tracks through the TDC Play service or the rise of internet-based portals for long-distance microfinancing and interactions with African entrepreneurs such as MYC4 and Kiva. Since Kiva was founded in 2005, 636,949 lenders have invested USD 255 million in poor entrepreneurs in remote areas of the world. The entrepreneurs have grown their businesses and repaid 99% of the loans. Both examples highlight the recent explosion of colours on the palette of delivering valuable customer experiences. The message to old Ford is simple: Black is no longer the only option.

While the shift can be described as an overarching trend, it is evident that success can still be found in all quadrants (Figure 2). Customer needs differ across segments and markets. Industries compete on different factors. In some cases, an attractive opportunity can be exploited by developing simple and convenient products that attract non-users and, thus, expanding the current market. In other cases, advanced experience-based solutions can be leveraged to capture the profitable high-end of an existing market. However, it is clear that competitive advantage as a rule of thumb is more sustainable when solutions are hard to imitate as well as based on deep and enduring customer relationships.

Above all, the uniting discovery across the spectrum of opportunities is the recognition of the need to carefully consider and design all elements of the business model to address the specific needs of the particular customer segment. The explosion of colours on the design palette has created an unprecedented range of opportunities to be explored in order to find the right fit between the value proposition and the customers.

Develop new business models

Innovate your business models to reap superior returns

In essence, the scope of creating customer value propositions and, thus, competitive advantage has been expanded from delivering basic products to crafting advanced business models.

Professor Michael Porter captured this paradigmatic shift back in 1996 when he noted that a strategic fit among many activities is fundamental – not only to competitive advantage, but also to the sustainability of that advantage. Porter argued that it is considerably harder for a competing firm to match an array of interlocked activities than it is merely to imitate a particular sales force approach, match a process technology or replicate a set of product features. Therefore, positions built on systems of activities are far more sustainable than those built on individual activities.

Consequently, we have to revise the old dictum of ”building a better mousetrap” to make the world beat a path to our door. Although more than 4,400 patents have been issued by the United States Patent and Trademark Office for new mousetraps, and it is the most frequently invented device in history, the driver of long-term success resides not only in the mousetrap itself, but in the complete business model.

The business model view resonates with research on how to profit from innovation. The mousetrap approach clearly plays an important role. A tight regime of patents, copyrights and trade secrets is one component of the equation, but to commercialise an innovation or exploit a new business strategy, complementary assets are needed such as manufacturing capabilities, distribution channels, specialised services and a sales force.

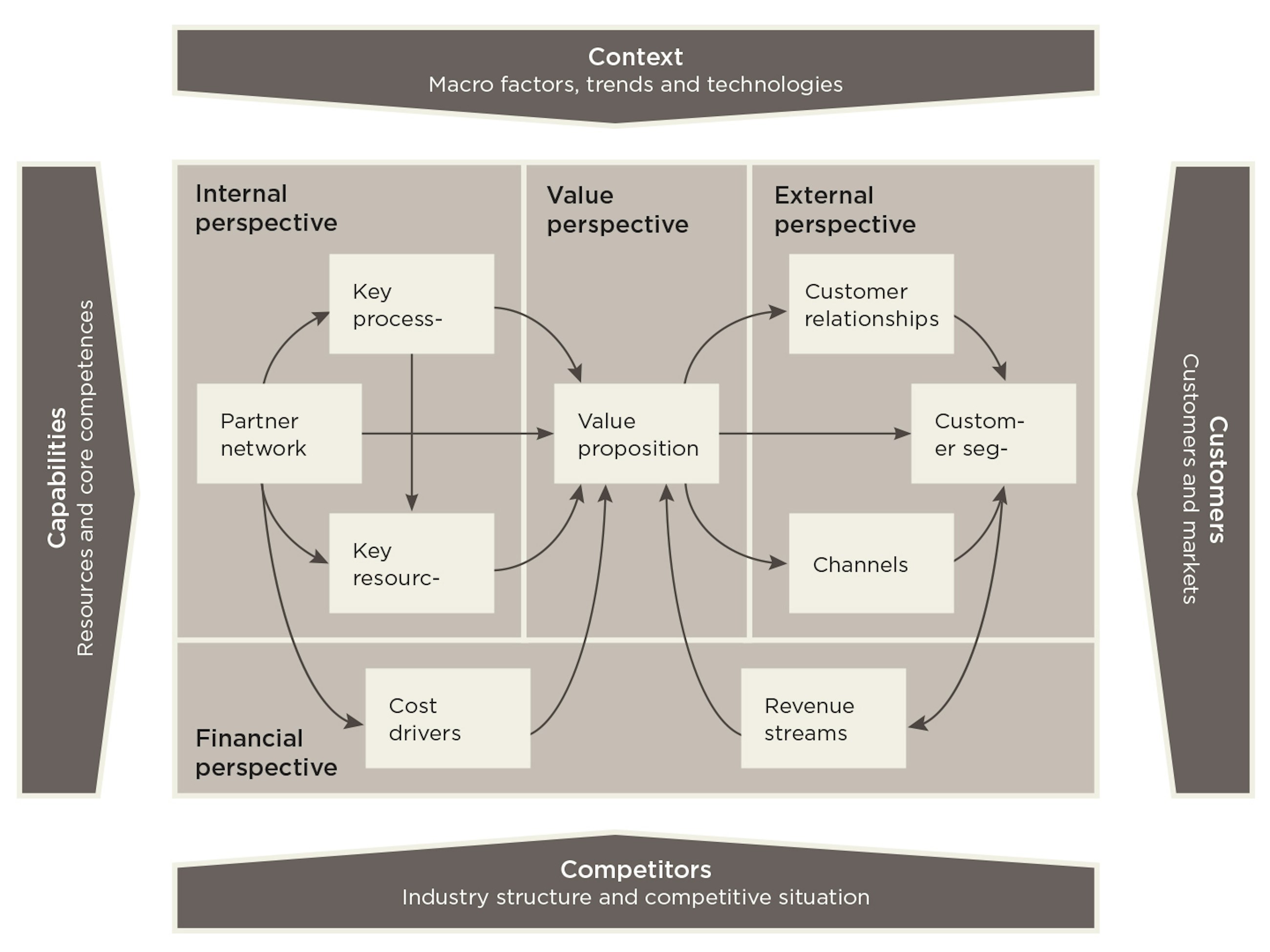

What is a business model?

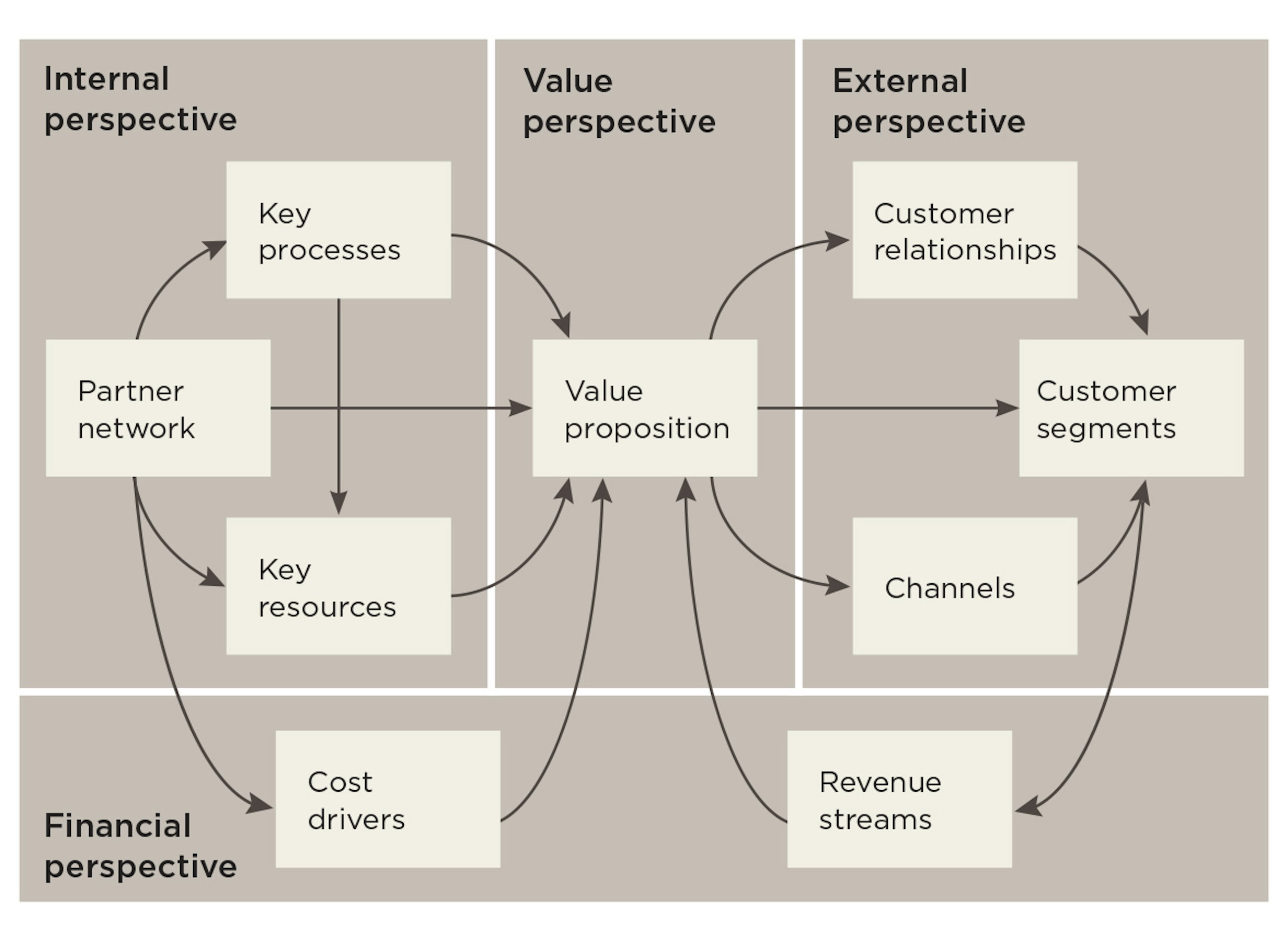

In brief, a business model describes how an organisation creates, delivers and captures value. More precisely, a business model articulates the content, structure and governance of the activity system that delivers a value proposition to the customer and enables economic value creation for all activity system exchange partners.

A simple example of customer needs being fulfilled by radically different business models is car transportation. Getting from A to B and the freedom to choose when to go can be served by a car that is bought, leased, rented or even shared with co-owners through car sharing services. The core product is essentially the same, while the activity system underlying the product covers a spectrum of business model design options. In all cases, value capture is enabled by the organisation’s ability to standardise and industrialise operations across the activity system. The aim is not to add complexity, but to enable scalability through simple, but effective activity systems.

The activity system can be illustrated using Alexander Osterwalder’s business model canvas consisting of 4 dimensions and 9 building blocks.

1. The value perspective

The value perspective describes the total market offering provided by the company. It consists of a value proposition composed by an integrated solution of products and services. Typically, the core offering is linked to complementary offerings to create a comprehensive customer experience. E.g. car manufacturers have recently begun to offer leasing contracts, which has proven to be an important complementary service to the core product that drives growth.

2. The external perspective

The external perspective describes how the value proposition is delivered to the targeted customer segments. To reach the customers, the value proposition is distributed and communicated through a set of channels, and to establish long-term customer relationships, ways of building the relationship have to be identified. E.g. car manufacturers have established a number of customer clubs – both online and offline – to build close connections to their customers.

3. The internal perspective

The internal perspective describes how the market offering is produced. A number of tangible, intangible or financial key resources must be leveraged to create the value proposition through a range of key processes. Strong brands are important intangible resources, and the design of processes both in back and front office functions is vital to economies of scale. Often, an external partner network is a key component of the value proposition, e.g. the financial service providers involved in the car leasing contracts mentioned in the example.

4. The financial perspective

The financial perspective describes how profit is made by identifying revenue streams and depicting the cost structure. Revenue comes in many shapes as the car example illustrates, and both financial components should be carefully designed to maximise profits and customer value.

The activity system is generic and can be used to systematically visualise and redesign any business model. Furthermore, it creates a unified language around the elusive business model concept that can be used across organisational functions and units.

Research undertaken by academics, global consultancies and our experience proves that a business model-centric look at value creation is imperative to business success. An IBM study from 2006 found that innovating across the business model had a much stronger correlation with operating margin growth over a five-year period than both product/service innovation and operations innovation. See figure 3.

A 2010 survey of the world’s top 150 companies confirmed the findings and discovered, furthermore, that a single-minded focus on product development tended to be a slippery slope. To increase investments in R&D proved to be fruitless, while a dual focus on both innovating the business model and delivering superior products actually enabled lowering the R&D spend. Apple – often described as business model innovator par excellence – has managed to significantly lower R&D spend as a percentage of sales while growing enterprise value at an extraordinary pace.

When executed in the right manner, business model innovation quite simply delivers superior returns to both customers and shareholders.

Decide on what game to play before innovating the business model

Obviously, all companies have a business model. Therefore, the key question is whether all elements of the business model deliberately have been thought through in a customer-centric way? Does your company purposefully design all elements of the business model, or are you focusing most of your innovation on improving the core product?

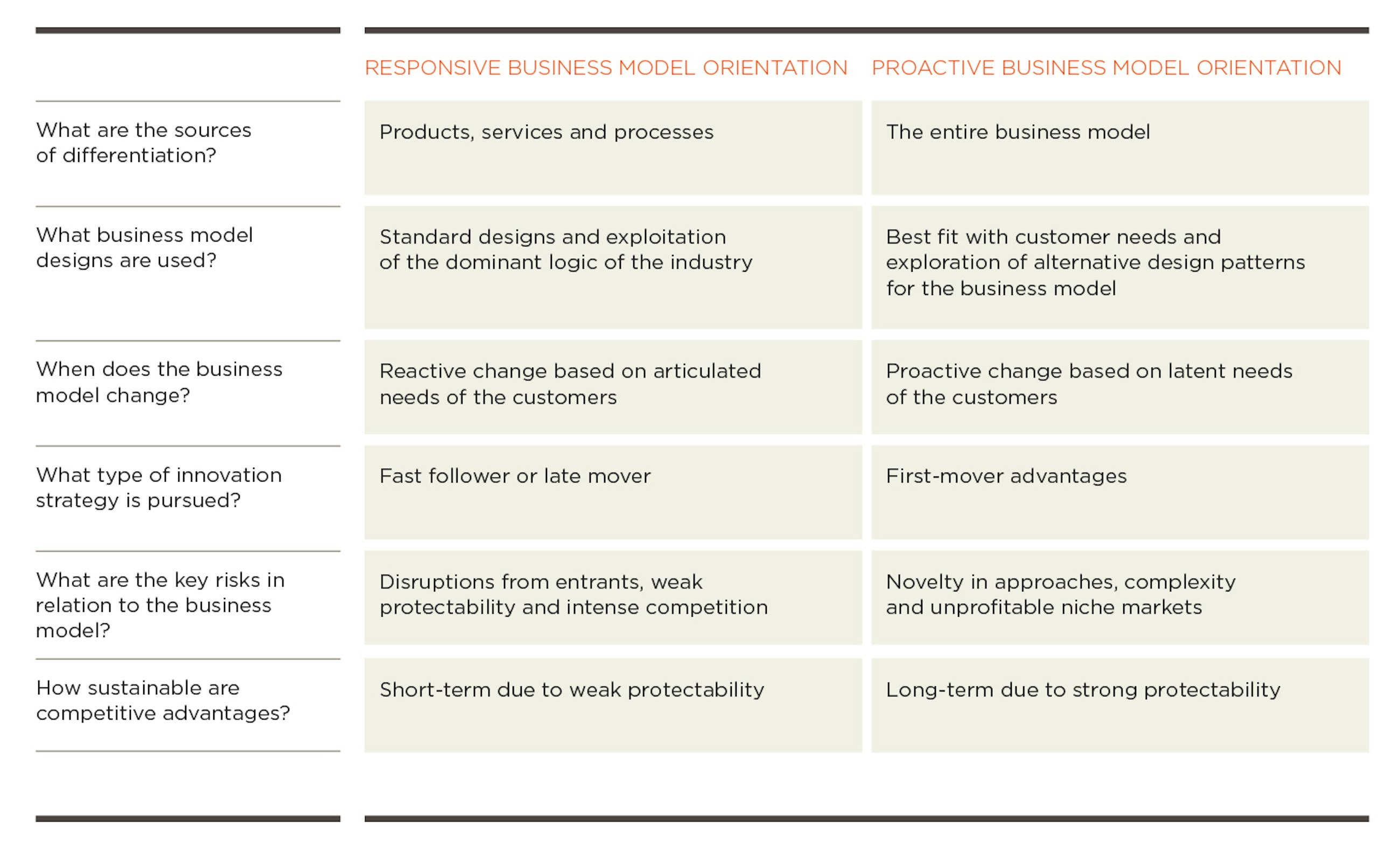

The complexity of grasping the entire activity system often leads to both overlooked areas as well as activity systems with designs purely based on the dominant logic of the industry. Consequently, in many cases, all eggs are put into the product innovation basket searching for differentiation through superior products while failing to see opportunities in other parts of the business model. In these cases, business model change is limited and fundamentally responsive. Large changes occur when changes in the environment require action and response. However, taking a closer look at the business model on a continuous basis in a proactive manner leads to a number of potential opportunities for customer value creation and growth. A proactive focus holds the promise of harvesting first-mover advantages, but obviously also the risk of designing a business model that does not deliver as expected.

Scrutinising the business model to discover new business opportunities places the customer centre stage by asking if the fit between current activities and customer needs maximises value creation for both customer and company.

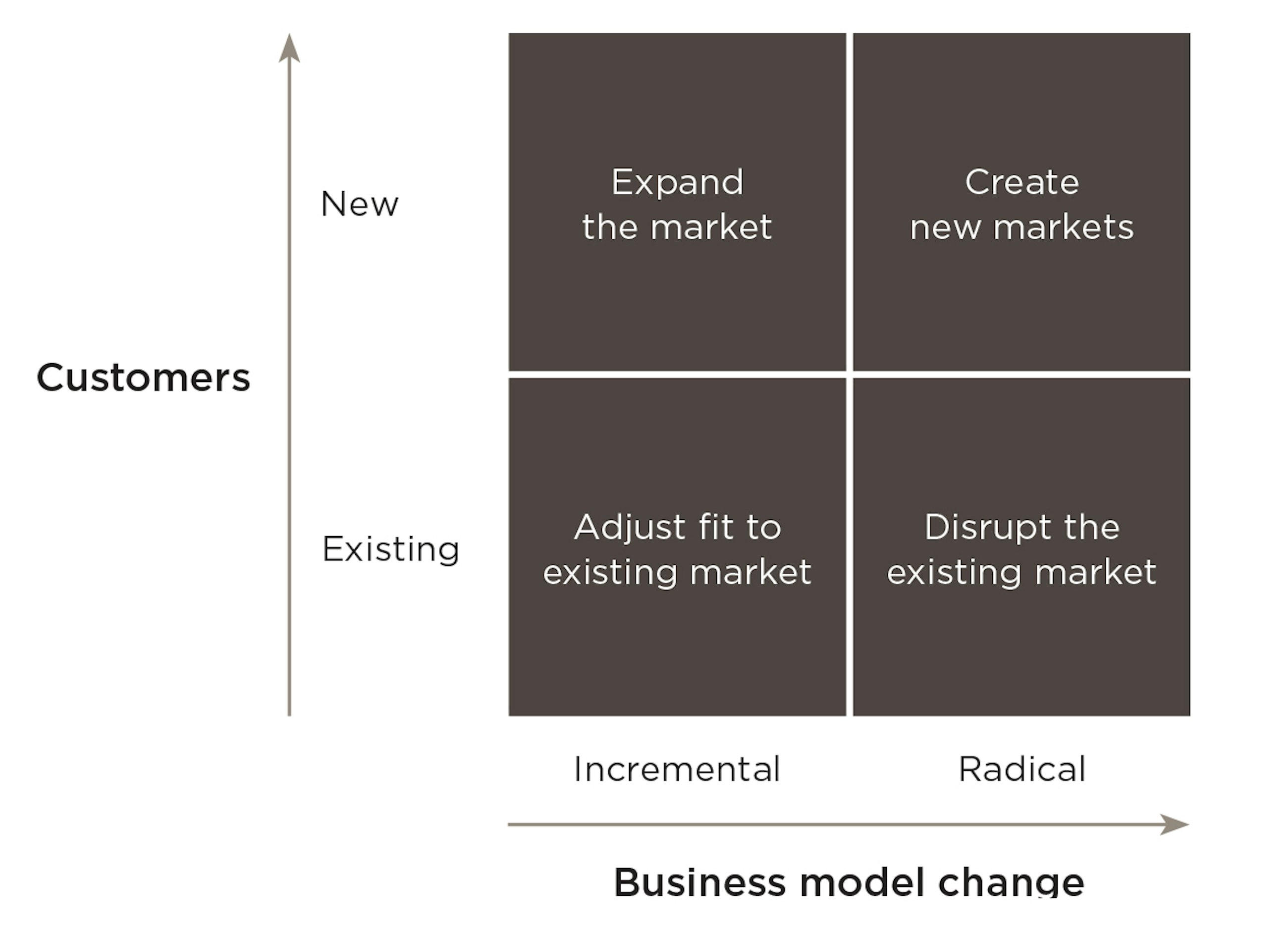

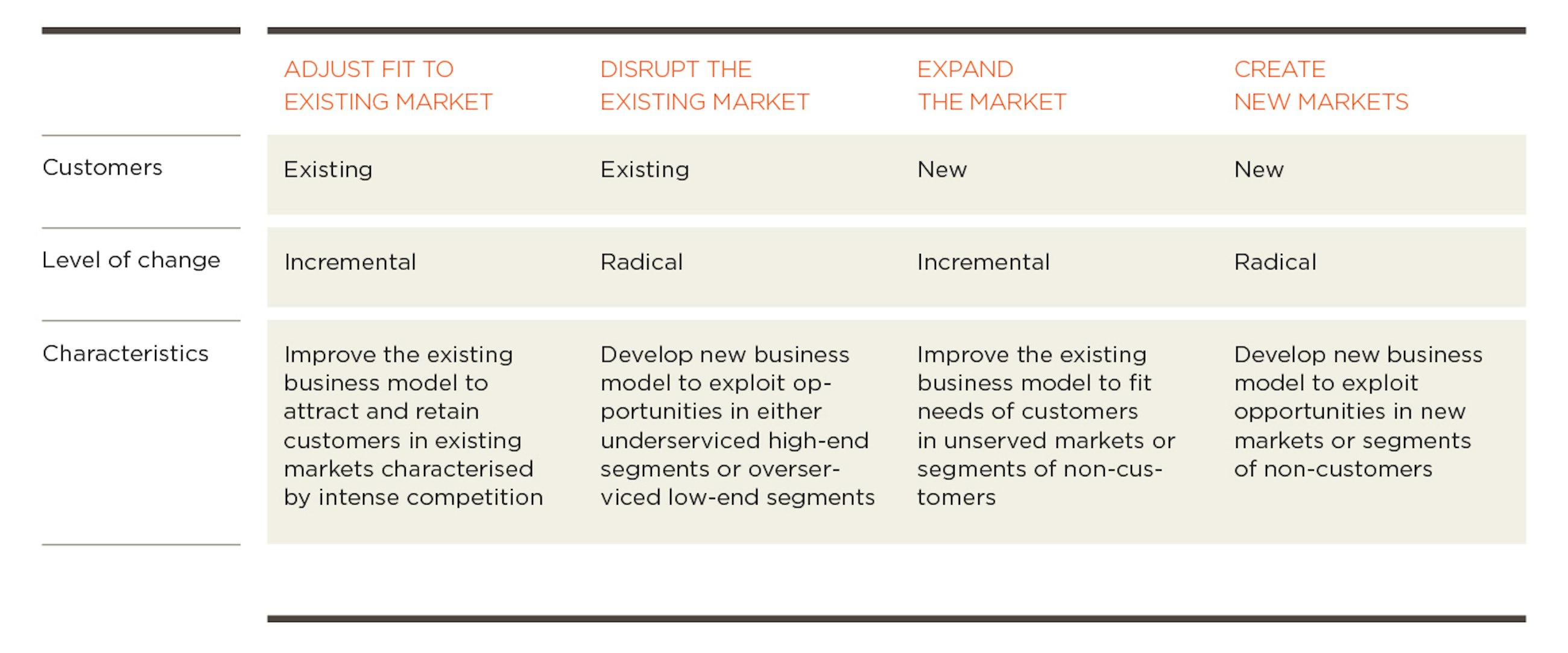

Four areas should be investigated to establish a systematic overview of opportunities to exploit business model design to enhance customer value creation. See figure 5.

Adjust the current business model to exploit opportunities in existing markets: Changing needs of existing customers and a turbulent environmental context present the opportunity to adjust the business model on a continuous basis. While competitors are focusing on improving products, simple incremental moves in other areas of the business model can be exploited to achieve important business goals. Launch a sticky value-added service, acquire customers through smart pricing models or partner with great companies to leverage their brand power.

Consider the role of value-added services in the telecom industry where TDC’s launch of the previously mentioned free music service TDC Play reduced churn by 50% for existing broadband customers back in 2009. The core product is essentially unchanged, while adding a service layer on top based on partnerships with the music industry changes the ”stickiness” of the business model dramatically. Few people are emotionally attached to their broadband provider, while the composition of a music collection is fundamental to signalling who we are and what we like. Adding a complementary music service has helped reduce loss of market share through improved customer loyalty and satisfaction in a highly competitive market.

As shown in the opportunity matrix, business model innovation does not have to be radical. Simple moves can achieve great results in existing markets and discover new differentiation factors.

Redesign the current business model to expand the market: Incremental change in the current business model can be leveraged to expand the market by attracting non-customers. For example, the practice of serving products in small and affordable sizes is a widely used strategy by global consumer brands to enter emerging markets. Seven out of ten Filipino smokers buy their cigarettes by the stick rather than by the pack, and as much as 68% of Procter and Gamble’s shampoo business in the Philippines is generated by sachet sales. The core product is left unchanged, while innovative distribution setup and packaging changes are keys to success.

Attracting non-customers can sometimes be achieved through small changes, and, thereby, a latent demand can be converted into real demand. Typically, non-customers are those who are either unaware of your offering or meet some sort of barrier to consumption. Understanding and removing the barriers are keys to expanding the market. Understanding commonalities in the non-customer segments paves the way for redesigning the business models.

Launch a new business model to disrupt the existing market: Investigating the needs of current customers in some cases leads to the discovery of attractive sub-segments which are not appropriately served by the current business model. The discovery of underserved or overserved customers leads to important managerial decisions. Should all segments be served by the same business model while running the risk of opening a flank for competitors? Or should a radically new business model be designed to serve attractive sub-segments while cannibalising the existing business model?

The dilemma is well-known in the telecom industry where a range of low-cost players with no-frills value propositions based on online self-service have disrupted the market several times. Recently, Danish low-cost mobile telephony provider Onfone was acquired by TDC after having captured a large share of the low-end market populated with customers looking for convenient, simple and cheap telephony. No-frills solutions, innovative pricing models and technology-driven automatisation are classic ways of conquering the low-end of an existing market. Ryanair and Google’s free web services spring to mind.

At the other end of the spectrum, the high-end of a market can be equally attractive to explore through new business models. Consider the makers of automated espresso machines powered by easy-to-use coffee capsules such as Nespresso. By removing the risk of failing to brew the perfect cup of coffee and reducing the time it takes to make a nice single-shot espresso, an attractive niche of espresso drinkers has been identified. Whereas high-end disruptions typically are based on a technology leap, low-end disruptions can also be achieved by simplifying and lowering costs.

Launch a new business model to create new markets: Designing radically new business models can be leveraged to create entirely new markets where large groups of customers have been locked out. In some markets, minor business model tweaks such as sachet marketing are simply not enough. A complete overhaul or even a new business model is needed to commercialise a value proposition for a new market. New markets can be defined both geographically such as bringing products from developed markets to emerging markets and as needs-based such as fulfilling emerging customer needs.

A business model currently under development illustrating the idea is the current debate concerning designing a house for the poor that can be constructed for under $300 which keeps a family safe, allows them to sleep at night and gives them both a home and a sense of dignity. It is a grand challenge that surely can only be solved by thinking innovatively about the entire business model. The potential is huge. 2.5 billion people at the so-called bottom of the pyramid live on less than $2.50 per day and are by far the largest global socio-economic group. Furthermore, fulfilling the vision leads to value creation that, by far, goes beyond pure economic value creation.

New market creation demands innovative business models. Moreover, these emerging markets are often judged unattractive to well-established companies, because they start out small and do not meet the expected growth rates to attract ordinary innovation investments. However, these markets often become large and profitable, and patience for growth pays off.

The four generic growth opportunities (see figure 6) can be explored and exploited by any company to sustain growth and delight customers. The common denominator is a proactive posture that recognises the need to cover all components of the business model – both when strategising at business unit level and when developing new market offerings. Obviously, new business models are not launched out of the blue, but rather closely aligned with overarching strategic growth ambitions of the company. In other words, a diagnosis of the strengths and weaknesses of current business models needs to form the basis for any attempt to pursue one or more of the four opportunities.

Combine diverse knowledge perspectives to create new business models

Becoming a business model innovator can be compared to an artist shifting style from painting with monochrome colours to using a palette with all the vivid colours of the rainbow. Options explode, and the number of possible solutions for designing the next market offering increases. However, in order to be successful, the colours on the palette need to be picked carefully. Not all colours can be used for the next breakthrough. In other words, the articulated or latent customer demand that is targeted needs to be matched with the best possible business model. In order to design new business models, options must be limited and focused on the most promising solutions to exploit the demand. Therefore, all efforts should start out informed. More precisely, four distinct knowledge perspectives must be explored and combined to extract insights and create the right fit between the market and the business model.

Customers: The customer perspective has already been discussed. At all times, a customer-centric approach is the right approach, which entails evaluating market options and establishing a foundation of deep customer insights. A key point when moving beyond simple tweaks of existing market offerings is the fact that asking what the customer wants will not be very helpful in most cases.

Firstly, the mainstream customer only experiences what he or she already knows and lacks knowledge about different options. The customer’s frame of reference is severely limited, and usually customer ideas cannot be used to leap-jump competition. They tend to be incremental and result in me-too products. Secondly, the knowledge that can be accessed easily by asking the customer will most likely not be very unique. All competitors will have access to the same knowledge through analyst reports and industry market studies. One exception is the so-called lead users who typically represent a tiny fraction of your customer base. They are characterised by their eagerness to tweak, modify and rebuild your products. Looking at their modifications can be helpful to identify emerging demands, since they are usually ”ahead” of the mass market.

Instead of asking the customers what they want, the best approaches for discovering unique insights are to listen and observe customers in their real-life context. To get under the skin of the customer, ethnographic research methods must be used, and data should be interpreted systematically to find the surprising insights which pave the way for innovation. While high-level quantitative analysis of customers can set the direction, deep qualitative studies are the best option to find the latent needs to exploit. Sharpen knowledge through exploring the full upstream chain of customers and understanding needs in all phases of the customer journey from initial consideration to disposal of a market offering. Put simply, get out of the building and meet the customers.

Context: The context perspective offers both constraints and possible solutions. On the one hand, a number of constraints can be identified by analysing macrofactors such as legal regulations, economic factors and societal trends. Often, constraints can be turned into great opportunities, which producers of outdoor ashtrays discovered when indoor smoking in public buildings was prohibited in Denmark some years ago. A simple change in regulations caused an instant boom in demand. On the other hand, many potential solutions can be discovered by studying the context. Both microtrends and macrotrends can provide answers to great experience design.

Due to the explosion of small digital sensors embedded in many consumer products, it is easy to measure almost everything that we do. Nike and Apple partnered and designed the Nike+ tracking device for runners. Fitbit has developed a personal tracking device collecting real-time data on every step taken, stairs climbed and calories burned. Both examples illustrate the booming interest in measuring and quantifying your everyday life. New technologies shape trends and can also be mapped to identify design options. A key area of interest should be emerging technologies and careful analysis of their possible implications for future business models. A simple but powerful exercise is to map 20-30 important technology-based trends and conceptualise a set of new solutions on the basis of each of those trends.

Competition: The competition perspective should without a doubt be explored. Competitive analysis can be used to single out those customer wants and needs which are not currently satisfied in the marketplace. Furthermore, an analysis of close competitors can be used to spot industry orthodoxies and mental models that could be challenged. Whirlpool observed that all white goods were designed and sold with women in mind, and they used that piece of competitive insight to create a new product line for men and their garages. While the idea might seem a bit sexist, business for Gladiator® GarageWorks is flourishing, and American men are eager to install designer fridges in their garages.

To identify and break out of industry orthodoxies, the analysis should not be restricted to close competitors when bigger and bolder ideas are wanted. Just as lead users and emerging technologies can inspire the discovery of new business models, so can research into analogous industries. Looking across industries helps identify emerging business model design patterns that can be imported from one industry to another. Danish playground producer Indu basically copied Google’s business model by offering ad-supported playgrounds to schools and communities for free. Looking across the industry value chain can also be used as a tool for identifying shifts in the industry profit pool. Small changes in the location of high profits in the value chain can be used to anticipate important changes and growth opportunities. The message is clear: When innovation ambition levels are high, an ordinary competitive analysis will not be sufficient.

Capabilities: The capability perspective is used to explore both internal and external capabilities and resources. Firstly, a mapping of internal capabilities and resources can provide insight about underused resources or underexploited business capabilities. For instance, the service business of many manufacturing companies has been professionalised in recent years. At Danish wind turbine manufacturer Vestas, the service business is growing, while the total turnover growth is under pressure. Services accounted for EUR 214 million in 2006 growing to EUR 700 million in 2011 out of a total turnover of EUR 6.4 billion.

Secondly, resources and capabilities of the business ecosystem should be mapped to identify partnering, collaboration and integration opportunities. A highly profitable business model in the publishing industry is to license forgotten comic book characters to toy, movie and computer game producers. In that way, resources are exploited in a new context through smart partnering agreements. Consider Marvel Entertainment’s lucrative licensing of Spiderman and X-men to Hollywood studios. If partnering opportunities are lackluster, a business ecosystem can be designed when the right incentives are present. External app developers play a vital role in Apple’s iPhone and iPad success. More importantly, the use of external developers and their resources reduces the risk of failure for Apple and increases the speed of innovation at the same time. Bad apps die, while Apple survives, and barriers of entry in the app market are so low that a 12-year old app programmer can achieve significant success. Apps are all about survival of the fittest, and in the heat of the battle Apple’s business model just gets stronger and stronger.

What are the characteristics of a great business model?

Not all business models are created equal, and some key factors must be considered when evaluating different design options. A delighted customer is the ultimate goal of your business model, but to survive in the long run as a business, the challenge is not just creating customer value, but capturing value as well.

To capture value, your design must provide a high degree of protectability through either legal or natural barriers. Legal barriers could be patents, trade secrets, copyrights or non-disclosure agreements. Natural barriers could be difficulty in reverse engineering your offering, switching costs or tacitness of relevant technology. To capture value, you must also have some degree of control over so-called complementary assets. Such assets are for instance manufacturing capabilities, an effective distribution setup, a portfolio of strong brands, innovative services and leverage of shared technologies. In other words, the strength of your protection mechanisms and supporting assets will determine your ability to capture value.

At the end of the day, great business models are based on solid financial models. To support your efforts in discovering the right financial model, consider some of the questions below:

- Do high switching costs create effective lock-in of customers?

- Can you easily scale your business model?

- Does your business model produce recurring revenues?

- Can you design the financial model so that you earn before you spend?

- Is it possible to exploit a partner network to reduce your costs and risk?

- Does your business model exploit protection mechanisms?

- Can you take advantage of existing assets and capabilities?

- Can you redesign the cost structure to change the rules of the industry?

- How can you rethink the in- and outflow of cash throughout both development and launch of the business model?

Altogether, new business opportunities are discovered at the intersection of the four knowledge perspectives. Know your options before innovating. A broad and diverse foundation of knowledge simply makes it easier to be both innovative and goal-oriented. However, the deep dive into emerging technologies, latent customer needs and inspiring business models should always be timeboxed and balanced with the innovation challenge at hand. There is no need to boil the ocean to design a simple service business on top of a product line. But bold moves do require a decent amount of knowledge and inspiration upfront.

The bottom line is that analysis must always serve a purpose and enable you to challenge world views. That also means that research efforts guiding business model innovation must be designed to build surprising hypotheses as opposed to just testing and validating predetermined hypotheses. Without the will to deconstruct orthodoxies, a desire to scan the periphery and proactive leverage of analogies from distant business models, your innovation success will be based on pure luck. We have to question our assumptions to change the rules of the game.

Build capabilities for business model innovation

Expand the scope of innovation and build capabilities for high growth

The first step in your journey to become a business model innovator will be to expand the scope of innovation to include all components of the business model. A key point is to actively manage all resources put into innovation. While the product development department is important, it is essential to uncover and coordinate all innovation work undertaken across departments. These investments in innovation tend to be hidden in budgets, but very important in real life. In marketing, they design great websites to support product launches. In supply chain, they invent new production methods. In business development, they identify potential targets for acquisition to create synergies. As an alternative to departmentalised work without coordination, companies actively pursuing the benefits of business model innovation open up silos and coordinate key activities. To get started, roles and responsibilities must be defined, and a process enabling coordination needs to be designed.

When innovating, there seems to be a hidden gravitating force pulling all efforts towards small incremental moves. In many companies, you will find portfolios crowded with line extension work and customer request projects that extend the past into the future. Obviously, these efforts are important to be able to exploit current opportunities. However, the second step in the journey is to think about innovation like great investors. They purposefully design a balanced portfolio of opportunities and put their scarce resources to work by calculating risk versus potential return. Experience and research show that a balanced approach has the largest payoff potential. Add to that the positive branding effects and employee engagement created in companies that are actively ”changing the world” as opposed to those companies just doing ”more of the same”. To get started as a business model innovator, management anchoring, innovation capabilities and a learning mindset have to be developed.

Create a strong innovation intent: A simplistic view of business states that you get what you measure. Hopefully, this is not always the case, but on the other hand, the saying has some merit. Especially when it comes to risky bets, organisational incentives have to support business model innovation. No one in the organisation will take on the risk of failing if corporate culture dictates that failure is not an option. Therefore, innovation goals must be backed by strong top management support and a very clear recognition that risk is an integral part of the game. When designing new business models, incentives should be aligned with fast learning and not fast growth. Harvard professor Clayton Christensen has put it nicely by saying that you want to promote impatience for profit but patience for growth when it comes to business model innovation. Particularly in the cases of large disruptive moves. Focus on early profitability pushes the innovation efforts to find the markets in which unique capabilities will be uniquely valued. Focus on fast growth makes you slip back to well-known business models in well-known markets.

A company exhibiting strong top management support for innovation is the Danish pump manufacturer Grundfos. The company’s innovation intent explicitly states that Grundfos in 2025 intends to employ 75,000 people compared to 16,000 in 2011, and that 50% of growth will come from new technology platforms. The ambitious intent has been decomposed to a number of strategic innovation platforms, and to support the realisation, different innovation processes have been designed for low-risk and high-risk bets. Low-risk projects are managed according to traditional stage gate development processes, whereas high-risk projects are rewarded for fast learning before scaling up the business. In some cases, companies seeking new growth beyond the core even decide to establish separate organisational units to support the very different ways of working as illustrated in the case of Grundfos. A strong innovation intent and a top management team walking the talk are pivotal to success.

Ask yourself if you have a clear management agenda for both renewing and reinventing the business model.

Establish entrepreneurial front-end innovation teams: As more than 70% of the total life cycle cost of a product is determined within the early stages of the innovation project, innovators can substantially influence the outcome by focusing on the front end of innovation. Success and failure are determined at a very early stage, so spend a little to learn a lot.

Firstly, the front-end innovation process must be extremely well-defined in order to ensure the right focus. Often, the front end is notoriously fuzzy, which is a classic stepping stone to failure. Instead, focus on installing a solid discovery-driven process where cross-functional and multidisciplinary teams led by heavyweight project managers are working on well-defined innovation challenges derived from the innovation strategy. Demand that teams are proactively looking for major customer problems to solve and actively exploring the four knowledge perspectives described above. If teams are eager to focus on creating myriads of ideas to begin with, they run the risk of creating ”solutions looking for problems”. This approach is counterintuitive and will lead to frustrations when they discover that there is no or little match between market needs and product ideas.

Secondly, it is important to recognise the need for establishing a shared vocabulary and toolbox when bringing people together with diverse competences. Innovation flourishes through cross-pollination, but without a common ”language” communication stifles. Therefore, entrepreneurial project managers with great people skills are a prerequisite when forming innovation teams. Common tools are also a key ingredient in and enabler of knowledge sharing and shared purpose. For instance, everyone in the team needs to get tools which bring them ”out of the building” to meet the customer and users in order to observe, interview and co-create with them. Simple tools will give your team a head start. If possible, teams should be co-located and even work on the same weekdays in order to maximise effectiveness. Framed by clear ambition levels and well-defined deadlines, such teams will power your innovation engine and be the key to identifying new paths to growth. To support customer focus and business model innovation, the discovery-driven innovation framework can be used.

Each step of the framework is supported by an advanced toolbox and innovation best practices.

Ask yourself if you have strong innovation teams dedicated to exploring and exploiting new opportunities following a well-defined and well-anchored process.

Master learning-based implementation: Having defined a strong innovation intent and formed entrepreneurial teams enable creation of new business opportunities. However, the tricky part of the equation is often a successful launch – in particular, if you are venturing beyond the existing business model. Simply put, you must use a different approach based on fast learning cycles where you plan to learn.

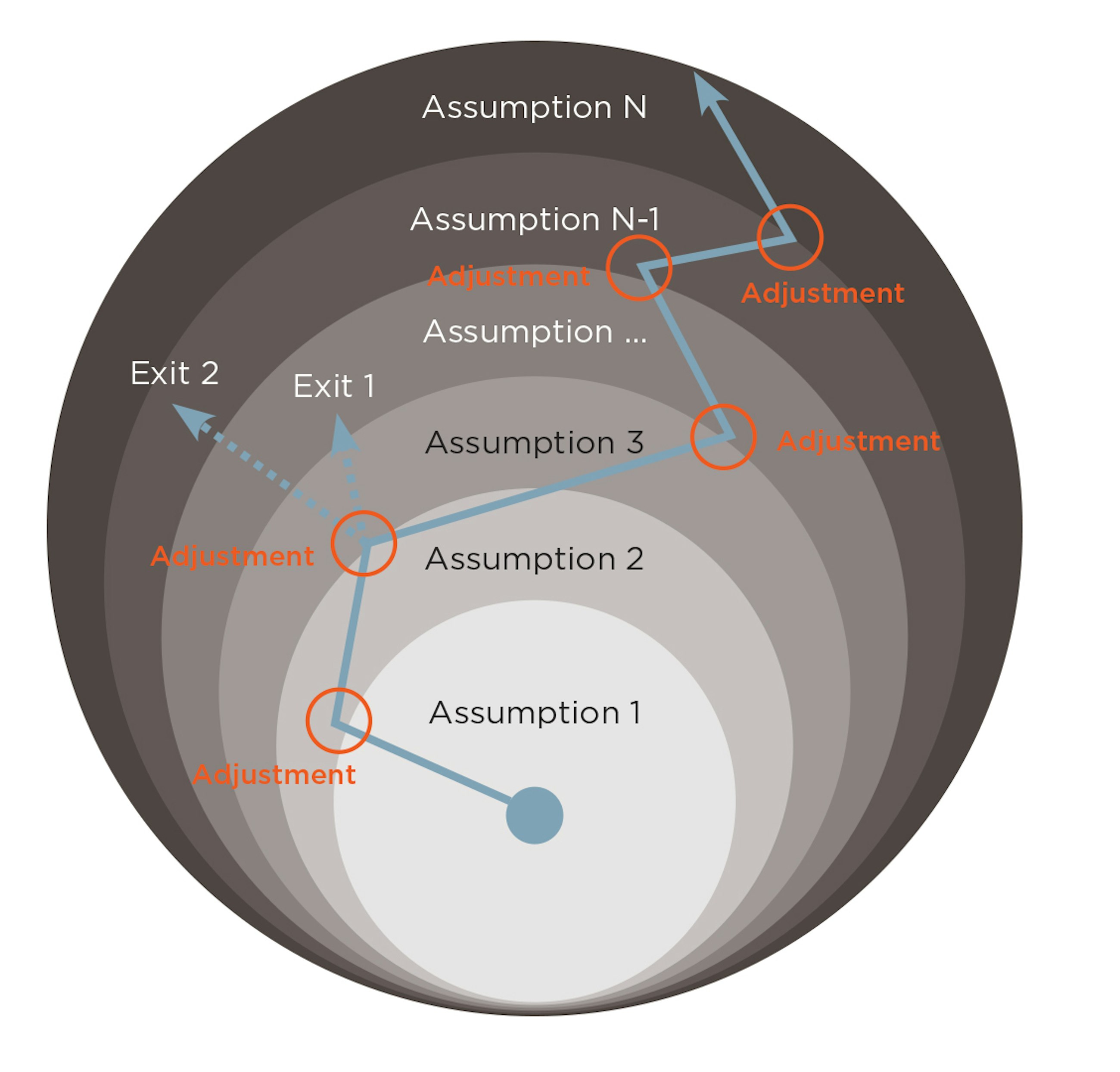

All new business concepts are fundamentally an interlinked set of assumptions which must be proved to hold true. But the assumptions are associated with different levels of risk, and instead of doing a full launch to test everything at once, you should learn systematically about your assumptions.

Define assumptions for each element of the business model, identify the level of risk and start by testing the most risky assumptions. In the early phases of innovation, testing rough prototypes and lots of iterations with customers will take you further, while test marketing and learning launches are used at later stages. Moreover, it should be a fundamental principle in your innovation process to work on competing solutions at the early stages. Developing concepts in parallel will not only enable learning about individual opportunities, but also enable you to combine feedback and extract new insights. A guiding principle for business model innovation efforts should be to reduce time-to-learning and increase the rate of customer feedback. Figure 9 illustrates how prioritised assumptions are tested and followed up by adjustments of the original concept – or even exit if the concept does not prove to be a valid solution.

Apple is often touted as being a revolutionary, but taking a closer look at Apple also reveals careful learning-based strategies behind every move at a higher level. The success of Apple was not created overnight, but rather through a step-by-step roadmap taking Apple from personal computers into the tablet market. The first step away from the old core was the iPod, and when success was ensured, the second step was the launch of iTunes. Hereafter, Apple ventured into mobile phones, copying the successful iPod razor and blades business model – expensive product and recurring revenues through sale of cheap music tracks – with the invention of the App Store. Thereby, the risk of failing was intelligently outsourced to app developers. Apple created a solid core product and a strong dual-sided business platform – a meeting place for Apple’s customers and app developers – while much risk was placed on the shoulders of app developers trying out different options. Apple was safe, while a lot of apps failed.

Apple’s ”open innovation” approach with strong reliance on a thriving ecosystem also points to the fact that partnering opportunities should be carefully considered when implementing new business models. Often, a great partner can both fortify competitive advantage and create a shortcut by leveraging their assets. Furthermore, different partnering options are also a possible way of escaping the invisible mental blinders of the core business.

Ask yourself if you have a strong learning orientation and proactively manage high-risk opportunities with the goal of learning as fast and cheaply as possible.

Altogether, the three principles should inform and guide all business model innovation efforts, and, obviously, the importance of the principles is correlated with the level of risk. On the other hand, all innovation activities and growth initiatives can benefit from gaining a fresh perspective from business model thinking and from rethinking your business model through the lens of discovery-driven innovation.

In a world characterised by exponentially increasing turbulence, expanding your innovation horizon to encompass the entire business model is timely and needed for gaining long-term competitive advantage. However, to stay true to the principles, we should not get caught up in too much theorising, but just do it and learn along the way. Close the laptop, get out of the building and learn from your customers to discover your future business models.

Further inspiration about business model innovation

Brown, Tim (2009). Change by Design, HarperCollins Publishers.

Christensen, Clayton M. and Raynor, Michael E. (2003). The Innovator’s Solution, Harvard Business School Press.

Hejlesen, Morten (2010). ”Danske pumper på afrikansk eventyr” i Innovationsantologi, Systime.

IBM (2006). Expanding the Innovation Horizon.

Jaruzelski, Barry, Dehoff, Kevin and Bordia, Rakesh (2005). ”Money Isn’t Everything”, strategy+business.

Johnson, Mark W. (2010). Seizing the White Space, Harvard Business Press.

Lay, Bill (2009). ”Getting Bullish on Business Model Innovation”, PRTM.

Markides, Constantinos C. (2008). Game-Changing Strategies, Jossey-Bass.

Martin, Roger (2009). The Design of Business, Harvard Business School Press.

Osterwalder, Alexander and Pigneur, Yves (2010). Business Model Generation, John Wiley & Sons.

Sehested, Claus and Sonnenberg, Henrik (2009). Lean Innovation, Børsens Forlag.

Zook, Chris and Allen, James (2001). Profit from the Core, Harvard Business School Press.