The missing link in change programmes

17 November 2022

Getting the organisation on board when implementing a new strategy, a new system or new processes continues to be one of management’s greatest headaches.

Despite acknowledgement that communication is key when implementing change, change efforts often fall short due to poorly designed communication. In this article, we describe some common misconceptions regarding change communication and share seven simple steps to make it more effective.

Most change initiatives start with the best intentions: to improve or optimise one or more aspects of the organisation’s daily operations. The problem is that most initiatives tend not to progress beyond the initiative stage. More than 70% of all change initiatives are considered to fall short in terms of their original intent. Why does change often die with the project that was supposed to foster it?

One overarching constraint is that the ability to provide clarity and engagement throughout a project is rare. A study conducted by Project Management Institute comes to the conclusion that poorly managed communication is to blame in more than 50% of failed efforts. In contrast, projects with effective communication achieve their objectives 80% of the time. Taking into account how vital it is for the success of businesses to implement change successfully, it is paradoxical how permissive many people are when managing communication. Often, change communication is assigned to the project manager as an additional task or simply omitted altogether.

Effective change communication does not just happen by accident. It is the result of an in-depth analysis and clear identification of issues related to motivation among employees, as well as obstacles and resistance to change. It should start well before the actual implementation phase and go beyond merely conveying facts and figures. The latter is particularly important – because anyone who thinks they can simply rationalise the change merely succumbs to the illusion that real communication has taken place. In truth, this can at best be regarded as information.

Information vs communication

Information and communication are not the same, and effective change communication needs to balance the two.

Information is a one-way street, typically formal in its tone and appealing to people’s rationality by comprising facts, KPIs, plans and roadmaps.

Communication, on the other hand, takes the form of storytelling that puts things into perspective, encourages sense-making and starts meaningful conversations. Communication has a more emotional appeal and, working in this field, we strongly believe that when it comes to organisational change, this form of appeal is more effective than logic and executive ethos.

More on change communication?0 5

Five principles to ensure profitable change communication

Five principles of how to design successful change communication that will create impact in your organisation.Change communication X-ray 2022

A health check on organisational change communication.Where is the fun in change communication?

Why humour is an underrated tool in change communication.Change Communication

An articles series on getting the full impact from your transformationsMost projects contain plenty of information, being full of numbers, checklists and plans. Strategy is pushed out by managers at meetings and in presentations and emails. This isn’t the way to win people over, because there is a total absence of willingness to involve and engage people and start conversations. Often, projects completely lack communication.

The successful implementation of change initiatives should start with the realisation that regardless of the objective and the content of the change, it is essentially about people who have to act differently tomorrow than they did yesterday. And people are anything but purely rational beings who behave according to the ideal of homo economicus. Decisions are not always made based on an all-encompassing pool of information and after weighing up all the advantages and disadvantages, but are instead made based on gut feeling. Uneasiness or even resistance to change does not always arise from a mere lack of information and can therefore be resolved much less frequently than expected by rational arguments.

A well-conceived communication strategy should therefore aim for a balance between rational and emotional elements. Without this balance, chances are that the desired change the project was intended to bring about will be doomed before it has ever had a chance to succeed.

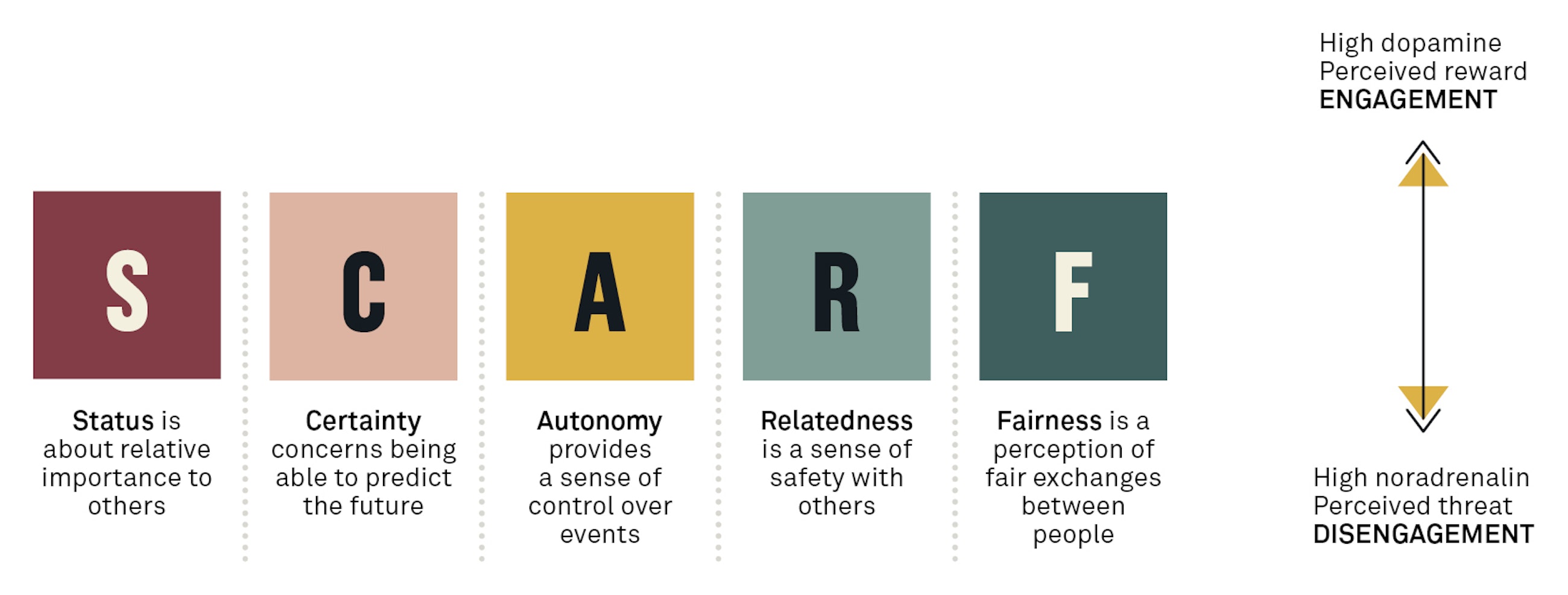

The SCARF model by David Rock, Director of the NeuroLeadership Institute, shows how strong, immediate and impervious to rational argumentation positive and negative reactions to change are. It draws on neuroscientific findings showing that people still respond to change using Neolithic behavioural patterns activated by the reward and threat centres. This takes place in five dimensions. The acronym SCARF stands for the following:

If important stakeholders feel that their autonomy is being threatened by a change that a project entails, they will react by withdrawing or even resisting. It is completely irrelevant whether the impairment is real or solely in the eye of the beholder, i.e., merely perceived as such.

An example: The implementation of SAP HCM means that managers will have to initiate certain HR processes in the system themselves in the future, instead of simply giving the order to an HR employee. The office manager of a sales branch, who has presumably ruled over his own small kingdom up to now, will perceive this as a reduction in his status and will react with resistance. This will not be possible to overcome, even using the most valid of arguments regarding efficiency and cost reduction in the interests of the entire group.

Good change communication will take this fact into account, with a mix of rational and emotional communication initiatives.

Five common misconceptions about change communication

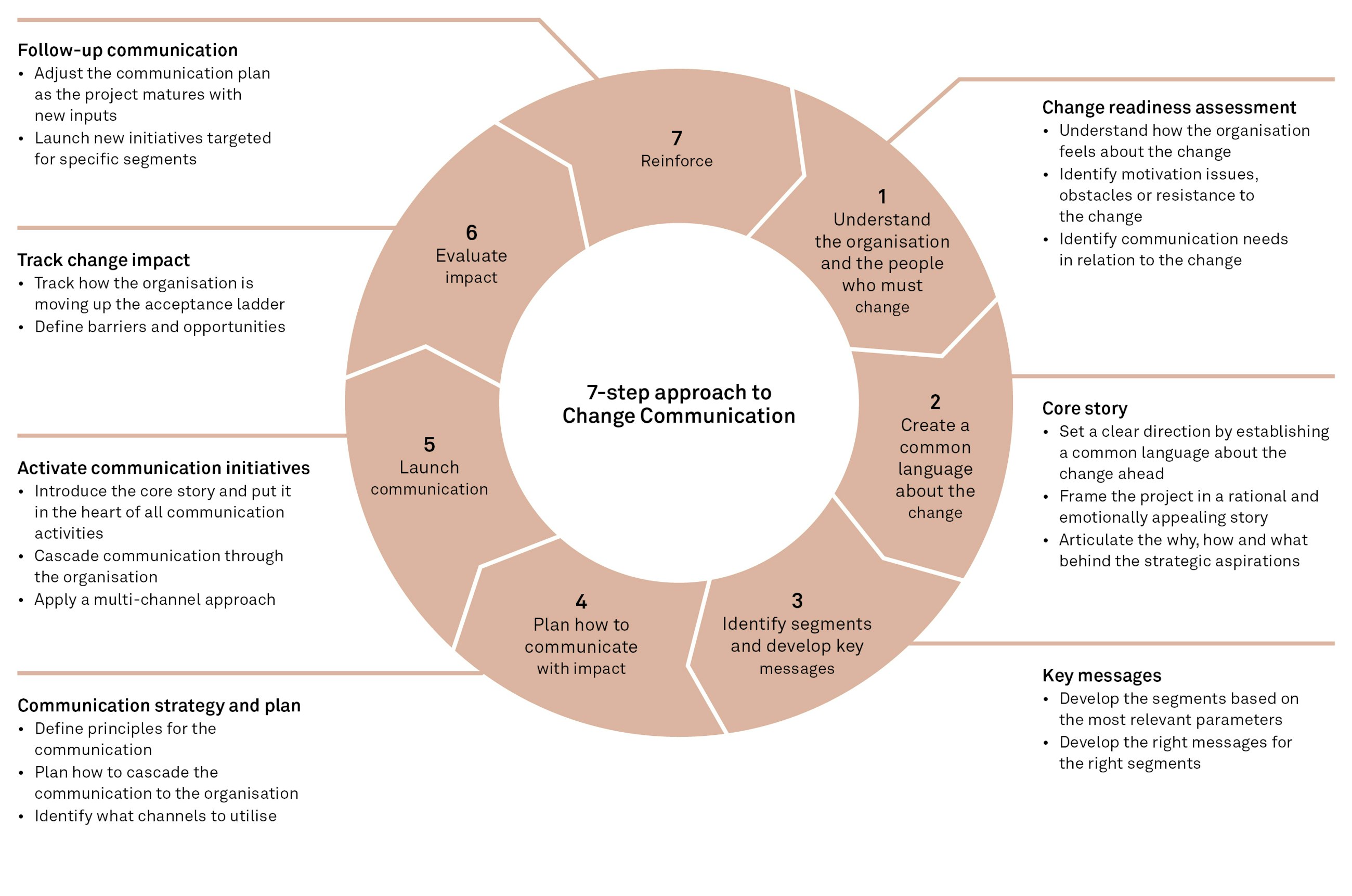

Nevertheless, when working with communication in a wide range of change projects, we encounter misconceptions, the most common of which we would like to briefly describe. In addition, we offer a simple 7-step approach for better change communication.

Misconception 1: Our employees will support the change because they have to

There is a big difference between accepting a change and supporting it. While silence and obedience are often perceived as support, in most cases they merely denote acceptance of the change. This is far removed from being supportive and motivated to embark on new behaviours. For a change to be successful, it requires vocal and committed ambassadors who take ownership of the success of the change.

Misconception 2: Our employees do not need the big picture

Telling employees half the story and expecting them to buy into it not only jeopardises management credibility – it is almost guaranteed to spark conversations about the things that have not been addressed. In other words, if management provides neither the perspective nor the purpose of the change, employees will make their best attempts to do so themselves. This automatically leads to guesswork, speculation and numerous uncontrolled stories, far from the original intent. When making change happen, it is not in anybody’s interest to cloak the organisation in mystery and confusion. On the contrary, the purpose and process should be evident and made transparent to limit the fears and manage the expectations of the organisation.

Top management: “It’s going to be super exciting.”

Employees: “Great. But it’s going to be without us.”

Misconception 3: Our employees see the world the same way we do

It is a human trait to project your own world views onto others, imagining that your counterpart is in full agreement. Unfortunately, communication in change projects is often no exception to this rule. If the communication with those who need to make the change does not reflect how they perceive reality, it will not resonate. Instead, it is likely to be perceived as irrelevant or even alienating. Similar to marketing communication, change communication must also be based on the insights of the target group – in this case, the organisation. For no apparent reason, retrieving insights from the organisation in an attempt to understand the hopes and fears within it is often neglected. Instead, the things that drive communication are based on what management considers important rather than the needs of the organisation. If you have ever wondered why change initiatives only ever remain a priority for management and do not become an organisation-wide journey, this is the most likely scenario. Our claim is that all managers will gain valuable input for implementing change with greater impact if they seize the opportunity to look below the surface of the organisation and understand the emotions that lie beneath it.

Misconception 4: If we do not have the answer, we should avoid the conversation

You know the type of person who always has the answer to everything? This is rarely a characteristic that builds trust or relationships. On the contrary, it often makes the person seem supercilious and overly self-sufficient. More importantly, it sends a signal to others that their input or assessment of the situation is not important or valued. Imagine how this looks in an organisational setting. When announcing changes, it should not be perceived as a weakness to not have all the answers. Instead, it is an opportunity to gain trust, as it sends a signal of honesty and lays the foundation for dialogue and involving the organisation in providing the answer.

Misconception 5: We gave them the facts and figures, so we should be on track

Numbers, data and facts are very popular at higher management levels. This preference is then often projected into the organisation during change communication, as it is intended to lay the foundations for a rational understanding of the change. However, rational messages should never stand alone when it comes to mobilising and involving the organisation, as they speak only to the mind. This is probably the most common mistake we make when implementing change projects: underestimating emotions. Speaking to the hearts of employees and recognising that all people are motivated by the fulfilment of a greater goal should be the most important factors in change communication where management is concerned.

If you recognise one or more of the above points, you are not alone. Despite an increasing awareness of the pitfalls of change initiatives and the importance of conducting some degree of change management, insight-driven change communication is all too often neglected.

Communication often ends up as an ad hoc discipline, executed in short bursts when launching the change. Of course, doing something is better than doing nothing. But occasional ad hoc messages will not get the job done. Often, people think that change can be communicated at a launch when introducing a new structure, process or strategy in the organisation. This thinking is not unjustified, as this is the moment when tangible change is supposed to occur. However, the foundation for change is laid months before, when the organisation is made aware of changes on the horizon.

Communicating a shared core story about the change before it actually occurs is paramount to winning people over and setting a common course. There is no reason to preach about the story. You are not trying to cross a desert. What is important is that it is communicated at the beginning of the project, with the aim of establishing a common language about the change ahead, fuelling new conversations and providing the organisation with a clear purpose.

So, if you are on the verge of launching a new change initiative, ask yourself: do you have the organisation on board? If not, feel free to find inspiration in this simple approach to change communication.

As simple as this approach might seem, it stands in stark contrast to how most change programmes are planned – firstly, because it sets out the phases leading up to communication being rolled out, and secondly, because it considers communication to be a continuous process rather than a tool. This implies that the organisational impact of the messages should always be measured as the project matures and constantly reinforces impact by adjusting the communication. Simply understanding communication as a well-planned stream of action, moving the organisation from awareness to engagement and ownership, will get you a long way.