Understanding cultural preferences

3 November 2017

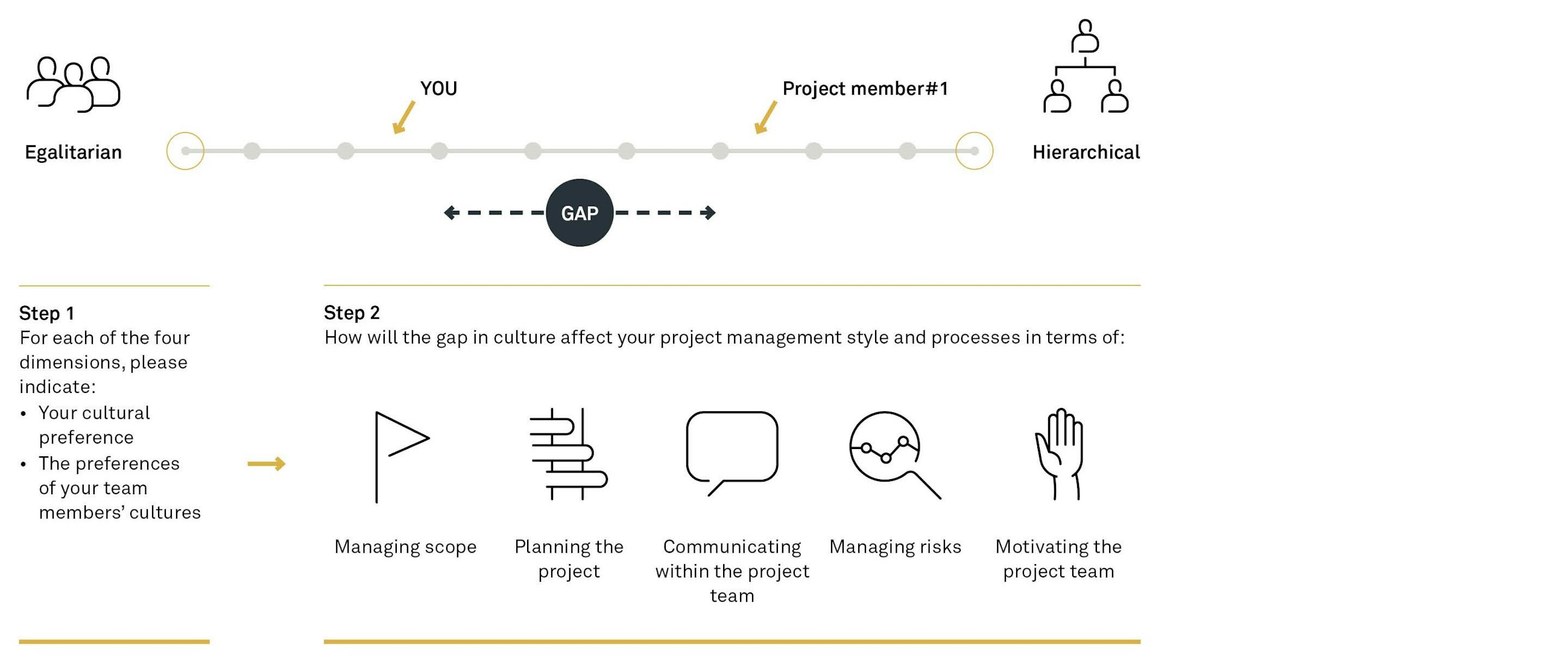

As project managers, we can make it easier and more efficient to work in culturally diverse teams by understanding our own cultural preferences and the preferences of our team members, identifying gaps and deciding on strategies to bridge those gaps.

Jens slammed his computer shut and stormed out of the door past his surprised colleagues. After the last conference call with his project team in India and France, he needed to cool off. Why can’t they just do things the way he proposed?

His Indian counterparts in the project team had communicated weeks ago that they are on track to deliver on time, but during this last conference call they reluctantly admitted to needing more time. Why did he have to press them so hard?

His French colleagues – at the same time – kept questioning his authority.

The alignment and communication hurdles he had to jump over during the last months had really taken a toll. Never would he have thought that managing this IT implementation project across international borders would pose to be such a challenge.

Jens started to question his decision to take the lead on this project. His track record had made him the ideal candidate to work on this high-visibility global project. But it slowly dawned on him that what worked well in Denmark might not get him to meet his goals and targets with this international team. The success of this project depended on Jens’ ability to understand the reasons behind his colleagues’ behaviour, to build trusting relationships with his project team and ensure that he communicated in a way that leads to the most effective collaboration of the team.

Managing global projects with team members dispersed across multiple time zones and nationalities has become the norm for most multinational companies. There are many opportunities of global project work like teams being able to work around the clock, pooling the best talent from across the organisation and benefiting from regional knowledge for localisation efforts. At the same time, the potential challenges for project managers also increase.

When we work with national colleagues who have similar core values and the same understanding of processes, there is often less need to explain the reasoning for our approaches and thoughts. The PMI Global Standards (found in the PMBOK) help to create a baseline for discussion among project managers and their teams. However, when we facilitate and execute projects with project teams that have spent their childhood, education and work life in diverse cultural environments, many of our own assumptions of “what is right and wrong” will be put to the test.

Some of the main challenges of cross-cultural project management are:

- Managing meetings and project deadlines across multiple time zones

- Accounting for cultural biases and different communication and work preferences

- Getting clear agreement across boundaries

- Building a team culture with a temporary, globally dispersed project team

As project managers, we can make working in these teams easier and more efficient by understanding our cultural preferences and the preferences of our team members, identifying gaps and deciding on strategies to bridge those gaps.

Cultural Differences

Besides our personal preferences and personalities, we are also an active part of groups that shape our opinions, belief systems and values. National cultures like French, Danish and Indian have found to differ on cultural dimensions that were researched and developed by Hofstede, Trompenaars, Hall and many more. These dimensions are a great starting point to develop more sensitivity to differences in work and communication style. At the same time, we should remember that groups cannot be reduced to a single score on various dimensions. An individual can deviate from a norm and our assumptions need to be tested.

What is also important to realise is that these cultural continuums do not have a positive and negative end, meaning one side is not better or worse than the other. Both sides of the spectrum are heavily context-related and function well in their respective environment.

Hierarchical vs egalitarian

Some cultures tend to put a lot of emphasis on the status of the person they interact with. You can see this play out in decision-making processes and leadership behaviour. In hierarchical cultures like India, Brazil and France, it is important to know where someone stands in relation to yourself. For a project manager, this can mean that visible support from a high-ranking manager and a more directive approach in making decisions are needed. Egalitarian cultures like Denmark or the Netherlands, on the other hand, have a tougher time with those that play on their status too much, or put themselves in the spotlight. Their consensus-driven managers are often perceived as lacking authority and weak decision-makers in other cultural contexts.

Direct vs indirect communication

Communication styles can be starkly contrasting between cultures. While there is, of course, a variety in the personal preference, you will find that people adhere to certain rules in a business context. In direct cultures like Denmark and Germany, it is considered rude to “beat around the bush” and deemed constructive to give critical feedback in the moment. In indirect cultures, a similarly blunt statement could be considered rude, impolite and extremely disrespectful towards the person’s reputation. Saving someone’s face is an art form in many conversations in Asia, for example. Especially in virtual work environments, it is important to consider what medium is used (email, chat, conference call, video call) and how to elicit input from less direct communicators.

Monochronic vs polychronic

Our perception of time is influenced by the culture that we grew up in and live in. In certain cultures, time is relative. Polychronic cultures like Indonesia and India have a more fluid understanding of time and typically work on many different things at the same time. You can see this in a looser interpretation of meeting timelines and deadlines, and a flexibility for spontaneity. Monochronic cultures like Germany, Denmark and the U.S. prefer to look at time as a linear, definitive thing. Visible characteristics of these cultures are back-to-back meetings, “time is money” mindset and a preference for punctuality. The view on relationship building while working is a major differentiator, which connects to the next dimension.

Task vs relationship

Whether you start a project or a meeting, what do you focus on: the people or the task? There are proven differences in our preferences towards one or the other. Those from task-oriented cultures (for example, Denmark and Germany) tend to dive straight into the topic with little “chit-chat” or time for small talk to get to know the project team members. It is assumed that you will get to know each other through the work process. Those from relationship-oriented cultures (for example, France, India and China) typically prefer to spend a longer time getting comfortable and finding out about each other’s professional and private background before getting to work.

When you build your project team and kick off the project, it is helpful to remember these dimensions. Most cultures around the world value hierarchy and relationship as an important part of how business is done. Jens would therefore do well in thinking of ways to build more informal touchpoints with his colleagues from India and France. Additionally, the way we believe trust is built also differs significantly between cultures. While especially Northern European cultures believe that trust is a given, until proven wrong, the majority of cultures around the world believe that trust needs to be gained.

Temporary teams such as global project teams therefore often suffer from a lacking foundation of mutual understanding and approach. Ideally, the project manager – in this case Jens –allocates more time for trust-building activities and exchanges in the beginning of the project phase. When timelines approach or pressure mounts, these different underlying assumptions on how we work together and what is important can otherwise create unnecessary frustrations and conflicts.

Virtual meetings are almost inevitable when working in cross-cultural and remote teams

Here are some tips for virtual meetings and working across cultures:

- Use the video functionality of your platform whenever possible. Adding a live video increases engagement and adds more non-verbal feedback and cues to your conversation.

- Talk slowly and clearly. Even for people who speak the same language, talking slowly and clearly can be advantageous when having a virtual meeting. If you are not sure that you have heard or understood someone correctly, repeat a summary back to get a confirmation.

- Allow for small talk before getting started. In a virtual setup, we tend to dive straight into the content. For cross-cultural teams, where trust is lower due to less contact and personal exchanges, it is vital to set time aside to build relationships.

- Visualise key words and numbers. If you have not prepared a presentation, then you could use the chat panel on your platform to write down key messages, names or other hard-to-understand terms.

- Avoid slang and abbreviations. Using simple and concise language will make it easier for your team to understand the message that you are communicating. Make sure to check, during the call, that everyone is familiar with the abbreviations that you use.

- Be aware of your humour. Sometimes jokes will not carry across cultural boundaries or be received well when it comes to virtual meetings – if you are not sure that it will go down well, it is best to avoid.

- Overcommunicate those reactions you would typically show non-verbally. We often read particular reactions (for example, scepticism, disagreement, approval, excitement etc.) on someone else’s body language or facial expressions. Make sure to vocalise your own reactions to communicate them across the virtual meeting.

- Use open-ended questions to check that everyone is on the same page. Allow time for those participants from more indirect or hierarchical cultures to formulate a response.

- Send out minutes. A written summary of what has been discussed and agreed will help to ensure that everyone is on the same page and that everyone is clear on the next steps.

- Ask for feedback. Follow up individually with participants for their perspective, for example, on the speed that you spoke or if they were confused by any abbreviations used.

Intercultural competence for global project managers

Intercultural competence is generally understood as the ability to appropriately communicate and work effectively with people of other cultures. Culture can therefore be understood in a broad sense, for example, also as functional culture, organisational cultures (in M&As), national cultures or generational cultures. To be culturally competent requires that we build more knowledge, develop skills on how to bridge gaps but also change our attitudes to appreciate and value approaches and perspectives that differ from ours.

#1: Cognition

Each development starts with a good hard look at where you are standing right now. Building your cultural muscles is no different. In the case of culture, what makes it difficult is that we do not necessarily have a good grasp on what it is that defines our cultural identity. Especially for those who have never stepped outside their country lines to live abroad, the reflection on their home country’s values proves difficult.

What can Jens do?

- Ask for feedback from his foreign colleagues on his own style.

- Use cultural profiling tools (such as GlobeSmart, Country Navigator and CQ Cultural Intelligence Test) to build awareness of his own preferences and his colleagues.

- Reflect and enquire about his own non-negotiable values and biases and how to handle them being tested and violated in project engagements by other members.

- Hire a coach or participate in a development programme focused on building cross-cultural awareness.

#2: Attitudes

A first realisation that project managers often have in a global setup is that there is no one way of reaching a goal. Having an open mindset towards different approaches and evaluating alternative solutions or ways of working to have an engaged and committed project team are important realisations. It is helpful to carry that learner mindset and make it a building block of a diverse project team. The more transparent you discuss ways of working together, the easier it is to build a solid team culture.

What can Jens do?

- Assume positive intent – most of us are not trying to make our work life harder on purpose, asking for the reasons behind a certain behaviour will often clear up frustrations and foster understanding.

- Build more time for project planning and kickoff to allow relationship oriented and indirect team members to build trust and give input.

- Mix one-on-one time with group meetings.

- Take face-to-face project meetings in different locations to share the pain and see the local realities.

#3: Behaviour

Once we have realised our own filters and lenses and have established a learner mindset, we need to change habits to build intercultural competence into our project interactions. There are two techniques that can help: frame-shifting and code-switching. Both require that you have knowledge and skills to adjust your behaviour.

Changing your perspective (frame-shifting): Our cultural values and beliefs are what we unconsciously draw upon when speaking, thinking and acting. Shifting that frame of reference means to draw upon new knowledge on cultures and values different from my own (for example, a hug might be considered a sign of friendship in one culture, but would be offensive and intrusive in another culture).

Changing your communication style (code-switching): The practice of shifting the way you express yourself and communicate in your conversations based on the recipient (originates from multilingual speakers, but also concerns communication principles like directness, non-verbal expression etc.).

What can Jens do?

- Prototype and run behaviour sprints to test new communication and leadership behaviour with team members based on new learning and observation of what reaches the best results.

- Establish and repeatedly emphasise mutually agreed working principles, have them visible and hold each other accountable, be specific in how these principles are expressed behaviourally.

- Incorporate cultural learning sessions into team meetings (i.e. have one team member present something about the local business culture).

- Encourage different modes of feedback and communication (video conference, email, chat, WhatsApp group messages, online communities).

After a few honest conversations with his project partners and learning about his colleagues’ cultures, Jens realised that he had overseen a lot of elements that could have been misinterpreted by his colleagues. He, however, also saw the tremendous opportunity of turning this project into a development opportunity for himself. With new energy, he set out to draft an email to his project team to share his excitement and how much he was hoping to learn from them in the future.

Some final tips on integrating cultural awareness into your project management

- Project team and organisation: Initiate your own stakeholder analysis by mapping and considering the cultures of your team members. Also consider whether there is a mixture of cultures present in your key project stakeholders such as your steering committee. Continuously seeking feedback from your key internal project stakeholders will be the easiest way to ensure that all needs are being met and to facilitate effective collaboration.

- Motivating the team towards a common goal: A strong and well formulated project purpose will serve as a uniting force in your project work. This common goal will help you to overcome a great deal of individual differences.

- Communication management: Examine your wider stakeholder group including the customer or end user. Build different tracks into your communication plan if it is relevant to approach these stakeholders with varying strategies.

- Managing your project plan: If you have a team with a combination of monochronic and polychronic cultures, spend some additional time setting expectations for what you expect from each person by which deadlines when you initiate a task. Here, SMART (specific, measurable, accepted, realistic and time-bound) deliverables can help in the communication of expectations.

- Risk management: Consider if the cultures present in your team may have a different interpretation or affiliation/avoidance towards risk. Use frameworks and descriptions to explicitly set expectations regarding risks (for example, descriptions of risk impact on a scale of 1-4).

What about you? Have you been part of or led a global project team? What are your tips on working within cross-cultural project teams?